"Bombing" Brooklyn: Graffiti, Language and Gentrification [1]

John Lennon

[1] In Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49, Oedipa, the postmodern heroine of the novel, enters a deserted bathroom and is surprised by what she doesn't see: "She looked idly around for the symbol she'd seen the other night in The Scope, but all the walls, surprisingly, were blank. She could not say why, exactly, but felt threatened by this absence of even the marginal try at communication latrines are known for." [2] Like Oedipa, I too am threatened by the diminishing amount of graffiti that I find on the walls of my Brooklyn neighborhood. Everywhere I walk, pristine new developments dot the sky and new coats of paint cover specialty storefronts that cater to the young, hip and well-heeled. What was previously a working class Polish and Italian neighborhood is rapidly changing into one of the most actively sought after addresses in New York City. But the blankness is not complete yet, and by literally reading the marks that are bleeding through the fresh paint, we can capture and analyze a physical manifestation of the tipping point where a neighborhood radically changes from what it was to what it will be. What we will learn by reading these walls is fascinatingly complex: at the same moment that graffiti offers a subcultural opposition to gentrification, it is simultaneously being branded and rearticulated to sell the neighborhood to the highest bidder.

[2] As Polish bakeries are razed to make way for luxury condominiums, I realize that, unlike reading local newspapers or heading to community board meetings to get answers, an honest and open discussion of the change in my neighborhood can be found on its very walls. Weaving an analysis of the works of two specific writers, Miss 17 and Banksy, with a personal and subcultural history of graffiti, what follows is a freeze frame of a moment in the destruction and construction of a neighborhood that has forever changed.

Meeting Miss 17

[3] When my wife went into labor, I was sleeping. When she told me that it was time, I quickly stumbled out of bed, grabbed the suitcase from the corner of our 1 1/2 bedroom, L-shaped apartment, nervously held my wife's hand as we walked out into the hallway before I quickly raced to the street to hail a cab. That's when I saw Miss 17. Sometime in the middle of the night, as my wife and I slept, she marked her name on a doorframe opposite our building.

Fig. 1. 685 Manhattan Ave.

It was a small, numerical '17' with the one and seven bleeding into each other, bookended by two fat periods. While the tag was unremarkable, instantly, I recognized her. About a month earlier, when I was late for classes and hurrying to move my car to avoid (another) ticket for alternative street parking before hopping onto the "G" train, I almost ran directly into her. Taking up about five feet of The New Warsaw Bakery, her "throw-up" [3] stood tall and brash.

Fig. 2. 587 Manhattan Ave.

Every time I walked by that wall, without thinking, I would spend a second or two staring at the large seventeen, outlined in white with black fill in, and wonder about its writer. And now, as I was trying to repeat instructions on breathing that my wife and I both had (apparently badly) practiced in Lamaze classes, there Miss 17 stood, tucked into the right hand corner of a door, staring back at me.

[4] Although I have never written myself, being born and raised in Queens, New York, graffiti has always been a part of my life. After graduate school, when I returned to New York for my first tenure track job and began walking the streets of my Brooklyn neighborhood, I found myself once again being fascinated with the graffiti scene. In Miami, where I was a visiting professor the year before, I saw a lot of graffiti but the writing there was different—like many things about Florida, I didn't understand the style (both the graffiti and the loud clothing). But back in New York City, reading the buildings, I began noticing the same tags—'Kuma,' 'Pandasex,' 'Deja,' 'PK,' 'Neckface,' 'Kid'—repeated over and over again. I began playing games with myself as I walked, trying to imagine where the next 'PK' would be—he liked to place things above eye level, and so I would scan the rooftops and water towers to see his large bubble letters. 'Pandasex' liked vertical and lower level pieces; his letters were squished together, the thin lines running into each other, the "d" often getting swallowed by the "a." But during that first year of living in Brooklyn, I noticed that many of the tags that had been seemingly there for a long time were being painted over, and these names were no longer so easily found. [4] They were disappearing in large swaths of my neighborhood [5].

Fig. 3. North 7th Street (medium range)

Fig. 4. North 7th Street (close range)

Fig. 5. North 7th and Berry

Fig. 6. North 7th and Berry (wide view)

Fig. 7. View from "sevenberry" overlooking the gas station

[5] After the birth of my daughter, however, I increasingly saw "17s" on more and more walls. One particular night, running out to find diapers in one of the 24 hour bodegas found on Manhattan Avenue (which are now being converted over to specialty delis), I discovered many vertical "Miss 17s" on the pulled down grates in front of the closed storefronts. These tags were different from the small "17" across from my apartment and the large bubble lettered "17" found on The New Warsaw Bakery. This one revealed the sex of the writer (or at least I thought so) and also a different style—the 'M' and 'I' sat on two pressed down s's that hovered above the '17.' Because of this weaving together of language and the numerical figures, I began forming a malleable identity around her, raising many questions impossible to answer. Was this the age of the writer? An address? A statement? After this night, regardless if I only saw the numerical "17" alone or the horizontal "Miss 17," this fusion of language and numerals created an open ended narrative that I wanted to continue to read.

[6] The third (very) early morning later, at 2:57 a.m., officially marked my obsession with Miss 17. I know the exact time because it had been two hours since my daughter woke up and no matter how tightly we swaddled her, how long we rocked her or how many ounces of formula she drank, she continued crying. Not knowing what else to do, I brought the car around the front of the building, strapped my screaming infant into the car seat and, almost immediately, she fell asleep. But every time I stopped the car for more than a minute, she woke up again. So I drove throughout the neighborhood, heading up and down one-way streets, rolling through stop signs in order to keep a slow, steady five mile an hour pace. Like much of New York City, my neighborhood, which crisscrosses through the edges of Greenpoint and Williamsburg, resembles a piece of a puzzle with its angular streets and oddly-shaped avenues; there are very few direct roads and an abundance of angular one way streets.

[7] Greenpoint's history dates back to the 1640s when the Scandinavian, "Dirk the Norman" (Dirk Volchertsen) became the first non-Native American settler in the region (the Dutch West Indian Company "bought" the land from the Keshaechqueren Indians in 1638). The land was soon transferred to the Parae family who would be heavily involved in developing Greenpoint for the first 200 years of its existence, watching it grow from a small farm town to a prosperous shipbuilding town whose most famous claim to fame was that the Civil War's Monitor was built here. [6] Williamsburg's history is quite similar; while it was mostly agrarian in its early history, by the 20th century, most of its economic base was industrial with large factories built for manufacturing, waste management, sewage treatment plants and breweries. While certainly not in the original planning, these large factories with huge brick canvases would become perfect spots for graffiti writers to hit in the second half of the twentieth century.

[8] Both Brooklyn districts became working-class enclaves, and the various immigration waves of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries brought laborers from Germany, Italy, Poland and Puerto Rico to live, mostly harmoniously, in tight ethnic communities within close proximity to each other. After the severe economic downturns which hit many industrial centers throughout the U.S. in the 70s and 80s, factories shut down or moved overseas, and Williamsburg and Greenpoint experienced a depression. But beginning in the mid-1980s, there has been a "revitalization" of the area as a new influx of "immigrants" takes control. Its proximity to Manhattan (it's a four minute "L" train ride from the Bedford station to 1st Avenue), cheaper rents and large loft spaces first brought many artists into the area. Then middle and upper class renters and buyers, smelling a deal, quickly followed, and within a decade Williamsburg has become the new "it" neighborhood with Greenpoint and its more entrenched Polish community slowly catching up within the last few years. [7]

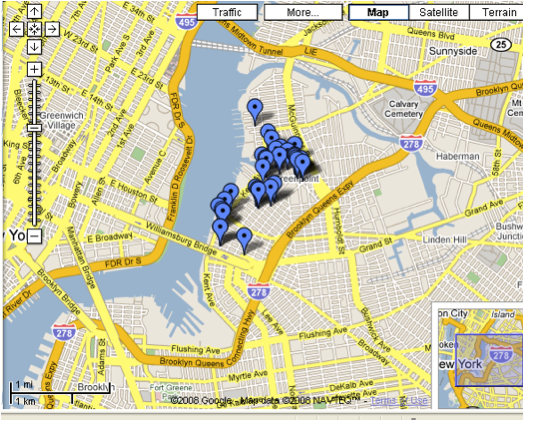

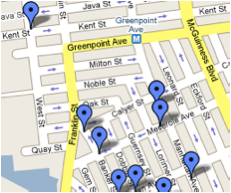

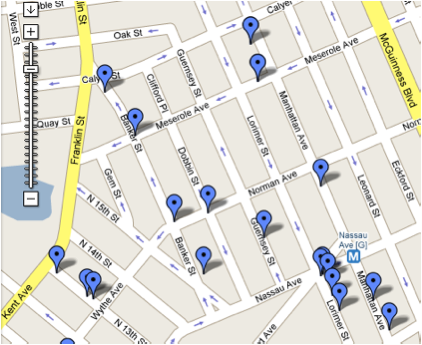

[9] Traveling that early morning with my daughter in the back seat, I didn't cover a lot of distance. We went no farther West and North than Manhattan, Driggs and Greenpoint Avenues, and no further South and East than the Williamsburg Bridge and the East River. Let's call the area "Greenburg" not only for simplicity's sake, since it combines sections from Williamsburg and Greenpoint, but also because this area, which has apartment buildings, McCarran Park, dilapidated river ports, a subway stop, small oddly shaped houses, a plethora of specialty and "Mom and Pop" shops, the Brooklyn Brewery, abandoned factories, luxury condominiums, wine and "dive" bars and a wide range of ethnic, gourmet, and cheap restaurants/diners, has its own history and identity that surpasses its traditional geographic boundaries. [8]

Fig. 8. An aerial view of all of Miss 17's graffiti in "Greenburg." It is a relatively small section bordered by the East River, the Williamsburg Bridge, the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, Manhattan Avenue and Greenpoint Avenue.

Fig. 9. A street level view of the first part of the path I traveled with my daughter when I discovered Miss 17's large presence in Greenburg. I started on Manhattan Avenue traveled North to Greenpoint Avenue and then South on Franklin Avenue (which turns into Kent Avenue shortly after Quay Street).

Fig. 10. The many switchbacks that I travelled as I followed the one way streets from Kent Avenue to Driggs Avenue spotting Miss 17s on the walls of places such as The Brooklyn Brewery, an abandoned Sugar factory and buildings along the waterfront. When Kent Avenue intersects with the Williamsburg Bridge, I made my way back North on Bedford Avenue.

Fig. 11. Bedford Avenue runs parallel to McCarren Park. I travelled northeast away from the park and then entered the area I first missed when we started out on our early morning journey. I found Miss 17 in abundance in this residential area that contains many apartment buildings, supermarkets, delis and small businesses.

[10] Although graffiti is ephemeral, it does have a political and cultural lineage. In order to understand what Miss 17 means to Greenburg at this particular historical moment, therefore, it is important to contextualize her movements within the larger graffiti movement that has been part of the daily life of New York City for the past forty years.

A (Compact) History of NYC Graffiti

[11] New York City graffiti as a phenomenon began on July 21, 1971. On this day, over their morning coffee, The New York Times readers were introduced to Taki 183, an office messenger whose job supplied him with the time and resources to "bomb" throughout the city. [9] Even though the article, "'Taki 183' Spawns Pen Pals," was tucked away on page 37, it was a siren call to graffiti writers and soon-to-be graffiti writers from all the boroughs to get their own markers and hit the streets. Far from deterring graffiti, the article showed that if you hit enough places, your name would be recognized. Taki's "pen pals" soon covered walls with many tags haphazardly placed next to each other, forming a mosaic of names to be read. The graffiti scene exploded with writers such as Joe 136, Barbara and Eva 62, Tracy 168 (who had over 70 members in his "Wanted" crew), Vic 156, Eel 159, Yank 135, Julio 204, Frank 207, SatyHigh149, all prolifically writing their names throughout the city. [10]

[12] This rise of the graffiti subculture coincided with the downward financial slump of the city that was awash in heroin. And while the revenge fantasy Death Wish (1974) or Walter Hills' campy The Warriors (1979) might be an exaggeration of what New York City looked like in the 70s, it was the view that most people outside, and many inside, imagined the city to be. With the "discovery" of the subway as a moving showcase for their names, cars were coated with tags criss-crossing the boroughs at all hours of the day and night. New York City, without a doubt, was the graffiti capital of the world.

[13] As Jonathan Mahler captures in his cultural history, Ladies and Gentleman, The Bronx is Burning, the infrastructure of the city in the 1970s was crumbling. But it was the detritus of the city that graffiti writers reclaimed and made their own by placing their names on the buildings and walls that were being slowly lost to decay and neglect. Norman Mailer, in his book The Faith of Graffiti (1974), described the power that is embodied in the act of writing graffiti: "You hit your name and maybe something in the whole scheme of the system gives a death rattle. For now your name is over their name, over the Transit Authority, the city administration. Your presence is on their presence; your alias hangs over their scene. There is a pleasurable sense of depth to the elusiveness of the meaning." [11] Although Mailer is being hyperbolic and New York City never expelled a death rattle, as thousands of names began appearing on walls, each one representing a person illegally using language to carve out subcultural ownership over private and city-owned property, it was obvious to City Hall that the "presence" hanging over "their scene" needed to be dealt with in a hurry. [12]

[14] It was during the 70s, though, that this subculture, almost as soon as it formed, began to fracture and change. With so many tags covering walls and subways, it was hard for writers to get noticed. After The New York Times article hit the newsstands, a more competitive atmosphere encompassed the scene as writers became concerned not only with the number of spots that they "owned" but also how their names aesthetically looked. [13] The piece (short for masterpiece coined by Super Kool 223), with elaborate colors, shapes and designs, was introduced, and the more simplistic tag began to pale in comparison. The graffiti subculture, while still taking place in the public realm, became a private conversation as writers competed in terms of size, style and elegance. "Wild Style" became the most highly praised and replicated form, with letters being changed and altered, and a new, highly sophisticated graffiti 'language' being introduced on the public canvases throughout the city. [14]

[15] What "Wild Style" introduced into the graffiti conversation was the term "artist." Taki 183 wrote his name in a very simple, straightforward form; he received his fame from the sheer number of his wall hits. He didn't need large canvases, nor did he need a lot of time. His desire was to "own" as many spaces as possible. But by the 1980s, graffiti started to move from the streets to the gallery walls, and writers, now seen as artists, like Jean-Michel Bosquiat (whose tag was SAMO) and Keith Haring, were hanging their works on gallery walls both in Greenwich Village as well as overseas. Graffiti was no longer an elusive subculture; it was part of the art culture. Graffiti could be still be seen on the walls and subways of New York, but now it had a national and international following because of the globalizing practices of the art world (for example, writers were paid to go overseas and put on graffiti demonstrations). Hollywood films such as Wild Style (1982) and Beat Street (1984), the documentary Style Wars (1983), the highly influential book Subway Art (1984), as well as the mass appeal of hip-hop that used graffiti on its album covers, show advertisements and clothing, made graffiti part of the mainstream popular culture.

[16] Graffiti in the 1990s and 2000s continued to evolve as some writers embraced the economic advantages that resulted from being recognized while others descended, both literally and figuratively, underground. [15] When New York City began to get its own economic legs underneath it, technological advances in graffiti removal became more readily available, and writers, who once could watch their subway pieces travel across the city, now saw much of their graffiti removed almost as soon as it was written. Writers, however, struck back. With the ability to "Broadcast Yourself" on such sites as Youtube and Flickr or the thousands of individual graffiti pages on the web, writing can now live on indefinitely—long after their graffiti has been erased from a particular wall. "Fame" does not result solely from people spotting a tag in a particular location, but instead from how many hits have been tallied to a webpage.

[17] Miss 17 emerged from this shifting graffiti scene, and her prolific writing has not gone unnoticed—there are multiple Flickr sites dedicated to Miss 17 with hundreds of photos of her Brooklyn writing as well as photos of her tag in Amsterdam and Germany. [16] But that early morning, driving around Greenburg with my daughter in the backseat, there was something more to my search than just a curious desire to follow a writer. Much like Quinn in Paul Auster's The New York Trilogy, who closely follows and charts the walking path of an old man in hopes of revealing clues about some intricate plot, that morning I followed and mapped Miss 17's route to see if she could tell me something about my neighborhood that was changing before my eyes. As I traveled down potholed streets and scanned the dark recesses of luxury condominiums under construction, I had this overwhelming feeling that if I could somehow link her tags together to form one large story, not only would I find a narrative about this particular writer but I would also understand the narrative of Greenburg as well.

Reading Graffiti

[18] Metanarratives, of course, are in place. Graffiti is a crime and Miss 17 is a criminal who, if discovered, will be fined and will face jail time. But what, exactly, makes her such a social pariah? [17] One way to understand graffiti is to contextualize the crime within a larger power struggle over the ownership of language. [18] Far from being just a straight-forward representation of the spoken word, written language has always been in the possession of those in power. This ability to control language is directly transferable to the ability to control the physical bodies of those less powerful. As Michel de Certeau states in The Practice of Everyday Life, laws are "written first of all on the backs of its subjects" [19] and there is therefore an intimate hierarchal link between the written word and the physical body. But graffiti writers break this link and rearticulate the power of the written word. By illegally writing on property, writers are taking control of language and, in the postmodern sense, chaotically playing with it in ways that are disturbing to those in power. As Crispin Sartwell writes in his article "Graffiti and Language," "We could say that it's an attempt to revamp or rearticulate authority, to read it through a new set of codes, to take control of it [...] instead of merely knuckling under to it. It's an attempt to take language back." [20] Words are the most readily and easily accessible weapons of choice, and graffiti writers obsessively inscribe what is usually the first word that people learn how to write, their name. But unlike the name given to them, these self-imposed names are cultivated and designed. [21] Through a form of creative destruction that is easily and cheaply (re)produced, writers are able to use their social marginality to control language and negotiate a (combative) relationship with society. While language implies a hierarchal power originating from above, writers use the language as letter-masks that symbolically mark their oppositional and elusive identity. Through graffiti, hierarchies are reversed as language is taken back by a subculture in a very physical contest and regurgitated onto the dominant culture's property. Those outside the subculture who would normally not come into contact with writers are then forced to interact through the reading process. And this dialogue is certainly argumentative.

[19] As Susan Philips writes in Wallbangin', a powerful cultural analysis of the L.A. gang graffiti scene, "The medium itself implies alienation, discontentment, marginality, repression, resentment, rebellion: no matter what it says, graffiti always implies a "fuck you." [22] Marginalized, writers enter into places of society and write on them, leaving their marks on the walls that announce and tattoo their presence long after they have disappeared back into the night. Just as Caliban learned language only to then curse his masters, writers learn the language of graffiti in order leave their curses for all onlookers to read. But while Caliban was punished for his indiscretion, Miss 17 has been able to hurl curses at society without being physically seen.

[20] Unlike Caliban who tried to lead a revolution, however, cursing in public does not make Miss 17 a class warrior. While there was a concentrated effort in the 1970s by the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCC) to read subcultures through the interpretive lens of class resistance and symbolic solutions to unsolvable problems, as David Muggleton outlines in The Post-Subcultures Reader, recent theorists of post-subcultural studies are examining the fragmentation and heterogeneity that members of subcultures embrace. Nancy Macdonald explains this change succinctly in The Graffiti Subculture writing, "Life and liberty are being risked here and it cannot be for the sake of hegemony alone!" [23] Instead of reading their actions through a strictly Marxian dialectic, theorists now see subcultures acting in loose networks that simultaneously contain many, often times contradictory, political stances. In the recent documentary Bomb It (2007), a documentary that examines the global graffiti movement from New York to São Paulo, these contradictions are abundantly clear. Although the graffiti shown certainly takes on the personality of the specific city where the writer is working, the film also shows that within a particular city, competing and contradictory articulations of graffiti share the very same walls. [24] Never meeting Miss 17 in person, I can only speculate about why she writes graffiti or why she chose to hit my neighborhood so vigilantly. It is therefore impossible to categorize Miss 17 as consciously offering "resistance" to the gentrification of my area. "Resistance," as Cindi Katz writes in Growing up Global, cannot take place if there is "no vision of what else could be" [25] and I am unable to read this revolutionary vision in Miss 17's graffiti.

[21] By writing repeatedly throughout my neighborhood, though, Miss 17 is still disrupting the gentrification process in Greenburg by offering a "counterliteracy" to the transformation narrative of my neighborhood. Dwight Conquergood in his anthropological examination of graffiti writers in Chicago writes that, "graffiti writing is a counterliteracy that [. . .] must be situated with the discursive and visual practice of power and control that it struggles against." [26] The very act of writing "17" over and over again is performative writing, making the public space of the street into contested zones of literacy, forcing the question, "Who owns language?" Regardless of her intentions for writing, her practiced "street literacy" struggles against the dominant narrative of gentrification by offering counter-narrative signs of "visual chaos" and "urban decay."

[22] There can be no speculation that Miss 17's writing is a destructive and illegal use of language. Miss 17 "bombs" neighborhoods, a term that has militaristic connotations, and her desire to place her name on buildings produces much collateral damage. Her name on a wall becomes part of that building and, for a time at least, physically alters it, causing concrete ramifications in the way both the building and the surrounding area are perceived. Simply by using language illegally and placing her moniker on a building, Miss 17 is lessening the value of the real estate. If her tags, in conjunction with others, proliferate throughout the neighborhood, they offer physical evidence of crimes that have gone unchecked, and potential buyers might be scared off from paying, for example, $575,000 for a one-bedroom condominium. According to the National Association of Realtors, property values in a community where there is graffiti can lose up to 15% of their home value. If the graffiti is vulgar or obscene, owners could lose up to 25%. [27]

[23] This perceived symbiotic relationship between graffiti and dropping real estate prices has not been lost on local politicians. In New York City, mayors from John Lindsay through Michael Bloomberg have established and funded anti-graffiti programs to combat these "quality of life" crimes. [28] For example, Graffiti-Free NYC, a government sponsored program that is presently seen as widely successful by Mayor Bloomberg, is a street-by-street graffiti removal program that has removed over 100 million square feet of graffiti. [29] More specifically in Greenburg, most store windows display $500 reward posters, offering money for information that leads to arrest and conviction of any writer. [30] Through the use of these reward posters, anti-graffiti educational programs and fleets of specially equipped power-washer vans patrolling the streets day and night, there is much concerted effort to control the use of language in these public spaces, thereby restoring an official narrative of Greenburg's transformation.

Banksy and the Selling of Greenburg

[24] Not all graffiti is, apparently, equal. While Miss 17's writing has been seen as destructive and there are active (and successful) attempts to erase her from Greenburg, there are others whose graffiti is being read constructively and used to sell the gentrification process in my area. Banksy, who is arguably the most famous graffiti writer in the world today, is a prime example. Self-described as a "quality vandal," [31] Banksy is a household name in Britain and widely-popular around the world although, until recently that is, no one could pick him out of a lineup. [32] In the early 1990s, around the time when rents began to rise in Greenburg, Banksy's tag and work began appearing in Bristol before spreading throughout the United Kingdom. First gaining fame within the graffiti scene, he was slowly recognized by those outside, publishing four volumes of his work, Existencilism, Banging Your Head Against a Brick Wall, Cut It Out and Wall and Piece. As his popularity grew, Banksy, always the savvy entrepreneur, began having (not so) secret shows/art happenings (like the infamous "Barely Legal" extravaganza that featured a painted live elephant), engaging his publicist to personally invite Hollywood stars like Jude Law, Keanu Reeves, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie for special V.I.P. exhibitions (it paid off with Pitt and Jolie buying a piece for a reported 2 million dollars). His work, usually done with spray paint and cardboard stencils, is very clear and readable, often ironically using iconic figures: Winston Churchill with a Mohawk, the Queen of England with a monkey face, Ronald McDonald surrounded by starving children. [33] Although he may have started his career vandalizing walls and trains in his home town, his work has appeared throughout the world causing minor and major sensations wherever they are found. Appearing (some with permission, some not) in the Natural History Museum, the Brooklyn Art Museum and the Louvre, his pieces, as a recent auction at Sotheby's confirms, are widely popular. In August of 2006, a Banksy suddenly appeared on the walls of Greenburg.

[25] The piece, discovered on an unused building on North 6th between Wythe and Kent, featured a stenciled black and white drawing of a girl, caught in the act right before a smile, skipping rope. Using greenish-yellow paint, the rope runs from her right hand, arcs around her head, through her left hand, down the wall, along the sidewalk, until heading up the wall once again where it finally connects into a stenciled replica of a large power outlet. Here, a stenciled back of a boy is seen reaching up to grab the switch and presumably, send volts of electricity coursing back through the rope to kill the girl. It is a disturbing although somewhat (darkly) humorous piece of street art taking up a large section of a wall, with the stencils meticulously drawn and the yellow line playfully sprawled on the sidewalk.

Fig. 12. North 6th between Wythe and Kent

Bloggers immediately recognized the piece as a Banksy, and on websites dedicated to the daily happenings of New York City like "JustNYC" and "Gothimist," [34] photographs of the graffiti surfaced, causing tourists to head quickly to Brooklyn. Someone forgot to tell the owners of the building the potential value of the piece, however, and unknowingly they painted over it. But that was only the beginning of the stencil's life. Soon the electrified girl would be resuscitated to help sell 1.5 million dollar condos.

[26] "Urban Green," [35] the development team behind a new luxury condominium very close to the building where the Banksy appeared, has placed a photo of his piece on their website's scrolling banner in between a photo of a young woman relaxing while overlooking the Manhattan skyline and a photo of a trendy local Thai restaurant. All references to the electrocution have been removed (the boy and the power socket are not present in the advertisement) and Banksy's piece now portrays the safety and "diversity" of the area to buyers, of whom it can be assumed would not like to see graffiti, especially the tags of Miss 17, on the side of their building.

[27] Banksy fully understands the way that his work will be read and interpreted. In his book Wall and Piece, Banksy reprints a letter from Daniel that he received on his website. In this angry letter, Daniel pleads with Banksy to no longer paint in his area because, almost counter-intuitively, his graffiti is making his area too valuable for working-class individuals to live in anymore:

I don't know who you are or how many of you there are but I am writing to ask you to stop painting your things where we live. In particular xxxxxx road in Hackney. My brother and me were born here and lived here all our lives but these days so many yuppies and students are moving here neither of us can afford to buy a house where we grew up anymore. Your graffities are undoubtably part of what makes these wankers think our area is cool. You're obviously not from round here and after you've driven up the house prices youll probably just move on. Do us all a favour and go do your stuff somewhere else like Brixton. [36]

Just like the "yuppies" and "students" who flocked to the area in Hackney because of the graffiti found there, the graffiti tourists (or "wankers" as Daniel would call us) who went searching for the Banksy piece are part of the process, whether we intend to be or not, of adding to the allure of Greenburg. By making our trek, we are changing the neighborhood.

[28] On a recent Tuesday night in The Turkey's Nest, a local bar that previously catered to factory men but now sells beer to a younger crowd decked out in tight black jeans and ironic t-shirts, I began talking about graffiti to an older man who lived in the neighborhood all his life. The conversation was impassioned with the man describing it as a crime that hurts his neighborhood. What became very apparent to me was that this man, who was literally and figuratively being pushed off his barstool by younger crowds who talked very eloquently about the meaning(s) of Banksy, was holding onto an idea of "his" neighborhood that no longer applied. He is right, graffiti is changing his neighborhood, but it is the "art" of Banksy's and not the "vandalism" of Miss 17 that is marginalizing him in this area where he has lived for 63 years.

[29] It is this attention, both negatively to Miss 17 and positively to Banksy, which crystallizes for me this moment of transformation, revealing a perfect case study of the way that subcultural oppositional practices are co-opted, its edges removed, and are informally sold as an "alternative" advertising motif. Miss 17's tags cannot be very easily repackaged; she is vandalizing a neighborhood and the aesthetic qualities of her tags are minimal to those outside of the scene. Her presence in Greenburg, and others like hers, must be erased as the area gentrifies. But while Banksy did not receive permission from the owners to do his piece, whatever oppositional stance the piece contained was very easily rearticulated by "Urban Green" as an advertisement; Banksy's irony is removed but his "art" remains in a controlled environment on the scrolling banner of their website. Looking at it online, the piece is obviously graffiti and quite possibly a potential buyer who is interested in art might even recognize it as a Banksy. But the threat that the "bombing" practices of Miss 17 embodies are completely absent.

[30] In another year, I don't think that Miss 17 will have much of a presence in Greenburg but the Banksy piece will still be used to sell condos. Graffiti will continue to exist in my area, it will just be made "safe" to enjoy. No longer profane, the language of graffiti will once again be in the hands of the powerful and the hierarchy of language, in Greenburg at least, will be restored.

Graffiti and Language

[31] This divide between the reception of Miss 17 and Banksy is not, of course, new to the graffiti subculture. Mailer, who saw the authentic graffiti subculture as dead by the time he began writing about it in the early 70s, interviewed "Junior" who derisively discusses the aesthetic practices of Wild Style, stating, "That's just fanciness [. . .] How're you going to get your name around doing all that fancy stuff?"(4). Junior is articulating the wide chasm between the two different types of graffiti that has, as seen with Miss 17 and Bansky, yet to be resolved. With the invention of Wild Style right through the more recent proliferation of wheat pasting, stickers, stencils and the new moves to virtually pieces in 3D, graffiti is increasingly judged aesthetically and not upon the labor involved in reproducing a tag enough times to get noticed. What Junior privileges is not the genius of the design or the reimagining of the shape or style of a letter, but the physical act of illegally reproducing language.

[32] Junior's statement is not only a discussion of aesthetics, it is also a discussion of semiotics. As Phillips points out in Wallbangin', in the English language, graffiti is a noun. While this may seem like a grammatical non-issue, this semiotic categorization separates the producer from the product, making "graffiti" something to be gazed upon instead of representing the actual process of writing. Graffiti, as understood in the global west, is a product, something that already has a physical corporality. The term "graffiti," in some non-Western languages, however, is a verb. This dramatically changes the view of graffiti as object that is complete and formed (and could, therefore, be used in an advertisement for a condo) to the illegal process of it coming into being. Graffiti understood in this way cannot be separated from a person writing and the time and space where it was written; it is the labor in a particular moment that defines graffiti.

[33] This semiotic lens is a productive way to think through the different types of graffiti that Miss 17 and Banksy represent—and in our freeze frame of this particular moment in Greenburg, a way to understand this tipping point of the gentrification process. In its noun form, Banksy's graffiti is something to be gazed upon, fitting easily into the fashionable "outsider" art category, and thereby used to bring potential buyers into the neighborhood. In its verb form, however, graffiti is understood as a polluting act, infecting the city with each mark on each wall; Miss 17's tags are understood as vandalism that need to be, like the older buildings where many of her tags are found, razed. As a noun, graffiti is an advertisement, as a verb, an oppositional practice that needs to be addressed.

[34] What we are witnessing in Greenburg is a reinterpretation of James Wilson and George Kelling's "Broken Window Theory" which states that to reduce the number of larger felony crimes like murder, assault and rape (and consequently raise housing prices), a concentrated effort is needed to stop "small" crimes like graffiti. Vandalism is a visual crime that signals a neighborhood on the brink of decline; clean up the graffiti and the neighborhood will keep the criminals at bay. But this view is apparently short-sighted and attempting to clean up all of graffiti is only one way to combat vandalism. Another is to restore the hierarchal power relations of language and control the way that graffiti is read and used. This, for me, is an expression of the tipping point where the neighborhood transforms into what it is in the process of becoming.

Miss 17 and Me

[35] Like Daniel, who posted the letter onto Banksy's website, I will also have to move out of my neighborhood because I can no longer afford the rent. But unlike Daniel, I was part of the reason why rents are rising. When I arrived in Brooklyn in the summer of 2006, we (barely) paid the $1500 dollar a month rent that helped push many of the Polish residents who have been here for years farther into Greenpoint—and consequently farther away from the subway and bus lines. But we cannot afford the rent that has been pushed to $1650 that my next door neighbor, a white twenty-something semi-college student who likes to play his drums when not playing X-box at 3 a.m. in the morning, somehow can afford. Next year, we will move to New Jersey, and I am looking at a multi-hour commute to work everyday. After being born and raised in New York City, I will become a "Bridge and Tunnel" tourist, a commuter to the city that I can no longer afford. Being a part of the gentrification process, in my less self-pitying moments, I can say it is appropriate that I would get burned by it as well. With this in mind, I realize that what Miss 17's "bombing" has given me is an appreciation for my neighborhood itself. Not for what it was in the past or what it will be in the future, but what it is right now.

[36] When my daughter wakes up in the middle of the night, or even sometimes when she just noisily rolls over, I place her gently in a stroller and walk her throughout Greenburg. As her eyelids droop and her pacifier becomes still, I search for Miss 17. I follow her route and I point out each one that I see to my sleeping infant. In searching for Miss 17, I become conscious of my physical connection to Greenburg. Because a "17" may appear in a small corner of a door or on the back wall of an alley, I have to move garbage cans or get down on my knees to look past obstacles. I begin to notice the buildings and touch their walls, feeling the cracks and the layers of paint on them. I look up at the top of the older buildings, notice the rusty and broken fire escape that Miss 17 faced as she placed her name near a water tower, allowing me to see the open windows that do not have air-conditioning units on these hot summer nights. I see the signs in vacant windows and I try to remember the old stores that are no longer there. I wonder why some grates have no graffiti and then stand close to smell the faint scent of new paint. By reading the walls of buildings, I am reading Greenburg. But it is a text that is disappearing before my very eyes. Many of the Miss 17's that were photographed for this essay have already been erased from the walls. She is disappearing, and her "bombs" will soon be memories as new buildings go up and new paint is applied. Very shortly, Miss 17 will be gone from the neighborhood. And so will I.

Notes

[1] I would like to thank my good friends and colleagues Christopher Robé (photographer) and Anthony Bleach who helped me record all of Miss 17s graffiti in Greenburg. I would also like to thank Matthew Burns for reading a draft of this essay. And, of course, this article would not have happened if it wasn't for ellie, whose birth and sleeping habits led me directly to Miss 17.

[2] Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49 (New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006), 70.

[3] A "tag" is a quick, easily reproducible stylized signature; a "throw-up" is a larger signature, usually done with an outline and one layer of fill-in; a "piece" is a large, usually intricate, design with multiple colors and images.

[4] Graffiti is temporal; due to its illegality, its wall life, depending on the neighborhood, is short. But there are easy ways to tell how old is a particular piece of graffiti. Some are dated (which makes it very easy), but after spending time looking at a lot of graffiti, one can also begin to understand its approximate age by taking into account the environment and weather conditions.

[5] As figure 3 and 4 attest, there is an effort to remove the "unsightly" graffiti that covers many factories and stores. In these photos, two men are removing graffiti, which has been there for many years, from a defunct gas station. In figures 5 and 6, the gas station can be seen in the mirrored window of the luxury condominium "sevenberry" that features one-bedroom apartments starting at $575,000. Figure 7 is a view from "sevenberry;" the gas station is in the forefront of the photo and a new condominium still in its construction phase is in the distance. The tearing down of the old and erection of new buildings is a common sight in this neighborhood.

[6] Frank J. Dmuchowski, "Greenpoint History." New York Architecture Images.

[7] For a detailed analysis of the effect of gentrification on the Greenpoint neighborhood, please see Justyna Goworowska's "Gentrification, Displacement and the Ethnic Neighborhood of Greenpoint, Brooklyn." University of Oregon theses, Dept. of Geography, M.A., 2008.

[8] Please refer to my interactive google map. Each bubble represents a Miss 17 found in a small section in Brooklyn. Click on the bubble to see a photo of that particular tag.

[9] Taki is the traditional Greek diminutive of Demetrius and 183 stands for the street in Washington Heights where he lived.

[10] There are multiple histories of the early New York City graffiti scene in print and on the web, many of them containing interviews with the writers themselves. For the best resource that I have found, see Art Crimes (www.graffiti.org) for a large database of graffiti-related articles and interviews.

[11] Norman Mailer, The Faith of Graffiti (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974), 3.

[12]One particular way that City Hall and the MTA combated graffiti was through "The Buff," which was a highly toxic shower for trains in which 50 gallons of heavy duty paint solvent removed the graffiti from the cars (See Craig Castleman, Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1984), 148-152.). Although Mayor Lindsey in 1972 declared "war" on graffiti, it wasn't until the introduction of the Buff in 1977 that things began to change, and twelve years and millions of dollars later, on May 12, 1989, every single train was declared "free" of graffiti (For a compact history of subway graffiti, see Roger Gastman, Freight Train Graffiti (New York: Harry Abrams, Inc., 2006), 60.).

[13] The graffiti subculture has always been a scene built on searching for fame and, consequently, is competitive. But as graffiti became more ornate and aesthetically driven, there was a more exclusionary practice based on artistic merit.

[14] While Wild Style forced interaction with bystanders due to its sheer dimensions, it also became less articulate to those outside the scene; "citizens" might be looking at more graffiti, but they understood less and less of what they saw. For example, in Joe Austin's Taking The Train (New York Columbia University Press, 2001), which chronicles in ten photos the changes of Phase 2's style over the decade from 1972 to 1982, there is an obvious, dramatic alteration in the legibility of the letters in his name. While in the first photo, the name is easily grasped, by the sixth it is extremely hard to read and by the tenth the letters are impossible to decipher. Phase 2 is reinventing language here as he literally tears up his name and reforms it in various shapes and forms.

[15] As police crackdowns increased, many writers began painting used and abandoned subway tunnels. Revs, a prolific NYC graffiti writer, went underground after his writing partner Cost was arrested. See Revs' interview in Bomb It (2007) for the writer's reasoning for heading underground.

[16] See http://www.flickr.com/groups/729720@N24/ for photos of Miss 17 from around the globe.

[17] Many millions of dollars a year are earmarked for anti-graffiti task forces in New York City. For example, Rep. Anthony Weiner (D – Queens & Brooklyn), a member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, announced a 5.75 million dollar initiative in 2006 to clean graffiti and monitor high risk areas. Mayor Bloomberg has been very tough on graffiti writers, expanding Rudolph Giuliani's "Anti-Graffiti Task Force" by adding a G.H.O.S.T. unit (Graffiti Habitual Offender Suppression Team), which searches out the most prolific writers in the city to arrest them.

[18] For more detailed analysis of the way that language and graffiti are connected, see C. Noble's "City Space: A Semiotic and Visual Exploration of Graffiti and Public Space in Vancouver."

[19] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (California: University of California Press, 2002), 140.

[20] Crispen Sartwell, "Graffiti and Language."

[21] Graffiti writers' monikers create personas that represent an identity outside of the legal system and therefore circumvent the modes of surveillance that are attached to our "given" names.

[22] Susan A. Phillips, Wallbangin': Graffiti and Gangs in L.A. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 23.

[23] Nancy Macdonald, The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity and Identity in London and New York (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 6.

[24] Please see http://www.bombit-themovie.com/, where there are transcripts of interviews with various writers that highlight the contradictory impulses and explanations for writing graffiti. While some view graffiti as "the world's greatest art movement" other see it as a combative "military mission" whose sole purpose is to destroy, "kill" and "burn" a neighborhood .

[25] Cindi Katz, Growing Up Global: Economic Restructuring and Children's Everyday Lives (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 253.

[26] Dwight Conquergood, "Street Literacy," Handbook of Research on Teaching Literacy through the Communicative and Visual Arts; eds. J. Flood, S.B. Heath and D. Lapp (New York: MacMillan Library Reference, 1997 (354-55).

[27] See the National Association of Realtors website.

[28] As TKid sarcastically asks and answers in the film Bomb It, "Where is this quality of life taking place? Not in my neighborhood," articulating the sentiment that these programs are directed towards economically enriched neighborhoods while poorer neighborhoods are left to fend for themselves.

[29] Jill Sheehy, "Got Graffiti?" Brooklyn's Progress, August/September 2007.

[30] See the official NYPD website for strategies that the police use to combat graffiti.

[31] Laura Collins, "Dept. of Popular Culture: Banksy Was Here," The New Yorker, May 14th, 2007.

[32] On July 13, 2008, Britain's Mail on Sunday revealed that Banksy is Robin Gunningham, a 34-year old native of Bristol, England. See Alex Altman's "Banksy: Unmasked," Time Magazine, July 21st, 2008.

[33] See Banksy's website for a view of some of his work.

[34] See "Banksy on the Streets of Williamsburg," JustiNYC, August 14, 2006 and "Banksy in Brooklyn," Gothamist, August 14, 2006.

[35] http://urbangreencondos.com/.

[36] Banksy, Wall and Piece (UK: Random House, 2007), 20.