R.S.V.P.:

Choreographing Collectivity through Invitation and Response

Emma Cocker

Nottingham Trent University

[1] An invitation establishes the tentative conditions wherein something might happen; it is an anticipatory gesture, always antecedent to something else. It gives permission; it makes an opening. An invitation requests a response; it contains an implicit instruction – réspondez, s'il vous plaît. You find the card on the table in a café as you are searching for the menu, or wedged down the side of your cinema seat, or fastened to the windscreen of your car. Or maybe it caught your eye as you were scanning the advertisements in the window of the local post office, or picking up a timetable for the next train home. There might have been a pile of the cards in the gallery that you just visited, or at the gas station, or the tourist information centre, or in that shop selling flowers. It could have fallen out from between the centre pages of your daily newspaper or else been delivered by hand to your own front door. You pick up the card and you read the text. The card is small, its letters neat and printed in black. An instruction is issued; the time, the place, the nature of the action set. (1) Within the next 24 hours, somewhere that holds personal significance, take the time to imagine yourself somewhere else or with someone else; or (2) Tonight in bed, before falling asleep, mentally retrace the paths that you have taken today; or (3) Next Saturday at noon in front of the City Hall, assemble facing towards the steps. Fix your gaze and remain completely still; or (4) At twilight tonight, meet at the harbour. Gather at the water's edge and wait before further action; or (5) At the Market Square, when it feels appropriate, using the square as a map, trace out the shape of your life's journey to the present; or maybe even (6) Tomorrow at midday on the high street, whilst walking, suddenly and without warning stop still. Remain like this for five minutes. Then carry on walking as before.[i] You, the recipient of the card, are invited to respond.

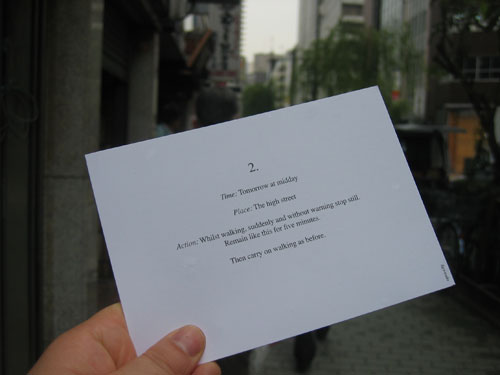

Fig.1. Documentation of Open City postcard instruction originally produced for nottdance07.

Text by Open City. (Photographer: Emma Cocker).

[2] The issuing of an instruction on a postcard is one of a series of tactics developed by the UK based artist-led project Open City, for inviting members of the public to participate in a performance, where the proposed events range in scale from an action or task intended to be privately undertaken, to the choreography of a more public gathering or collective endeavour.[ii] Open City was established in 2006 by artists Andrew Brown, Katie Doubleday and Simone Kenyon, and has since involved collaboration with other practitioners, writers and theorists (including myself). It is an investigation-led art project that attempts to draw attention to how behaviour in the public realm is organized and controlled – and to what effect – whilst simultaneously exploring how such 'rules' or even habits might be negotiated differently through performance-based interventions. Open City's projects often involve inviting, instructing or working with different individuals to create participatory performances in the public realm; discrete artworks that put into question or destabilize habitual patterns and conventions of public behaviour. Since 2007, instructional cards produced by Open City have been encountered by members of the public in different cities from Nottingham (UK) to Yokohama (Japan). Each card consists of an instruction or invitation, specifying the place, time and action of some proposed event. Often conceived in parallel to other Open City performances, taking place within the context of an art festival or exhibition, the instructional postcards were originally intended to extend the invitation of participation to a wider public (beyond the immediate art audience). The nature of the instruction often operates in dual terms; its invitation attempts to rupture the logic of daily or familiar routine by affirming the possibility of an alternative mode of (less habitual) action. This essay addresses the affirmative dimension of the invitation, specifically focusing on how certain invitational, instructional or propositional forms of writing have the capacity for producing experimental models of collectivity or sociability. Reflecting on my own collaboration with Open City, I interrogate how invitations, instructions or even propositional scores have been used to choreograph temporary forms of community within the time-space of a participatory performance; how certain sited writings have the capacity to produce communities of readers or respondents who become temporarily – and potentially visibly – bound by the terms of a given text.

[3] The essay is developed from my perspective as an artist-researcher working with and within the project discussed; its reflections gleaned from the embodied, live encounter with the work of Open City. It forms part of an ongoing reflexive research process through which to define and determine a critical context and vocabulary for further considering how the invitation might become used as a tactical device for producing unexpected or non-habitual models of sociability or communities of response. This essay explores how an invitation can be used to produce an emergent form of social assemblage or temporary collectivity, a model of being together based on an individual's capacity for being responsive to another's call.[iii] The invitation is examined on the basis of its potential to call forth or give permission for the formation of unexpected or non-habitual configurations of community or collectivity, no longer bound by existing rules or habitual societal protocol, but determined instead by an individual's decision to respond to or accept the conditions (or rules of engagement) set up by the invitation's textual frame. The example of Open City's work will be contextualized in relation to other contemporary and historical art practices that use an instructional approach to choreograph a form of collectivity or sociability through the dynamic of invitation and response. In turn, the positioning of the invitation as a tactical device for choreographing emergent, time-bound forms of sociability or collectivity will be considered against the wider context of contemporary theoretical debates that are attempting to rethink – and problematize – the terms of 'community', by conceiving its constituency beyond the determination of already defined geographical, social or economic criteria. In doing so, I intend to demonstrate that whilst Open City's use of invitational scores are modeled on the playful format of Fluxus instructions or propositions, they are not simply a contemporary reworking or appropriation of the past. Rather, through the work of projects such as Open City it becomes possible to conceive how different histories and lineages of practice and theory interweave, producing a new generation of invitational or instructional art works, reflective of current debates around the potentiality of those models of collectivity and sociability produced within and through contemporary art practice.

[4] My own practice as an art writer operates under the working title 'Not Yet There' and is concerned with exploring models of practice – and subjectivity – which resist or refuse the pressure of a single or stable position by remaining willfully unresolved.[iv] Prior to my involvement with Open City, I had produced a number of texts that addressed the resurgence of interest in the practice of wandering (and the attendant ideas of dislocation, defamiliarization and getting lost) within the work of contemporary artists.[v] Based on these research interests, I was invited to produce a piece of writing in response to Open City's work – to be serialized over a number of publicly distributed postcards – which would attempt to critically contextualize the various issues and concerns emerging from within their investigative activities. The postcards were commissioned as part of nottdance07 (Nottingham, UK, 2007), to supplement or support the performance-based actions that Open City were organizing as part of this citywide festival. For nottdance07, Open City proposed to work with members of the public to produce a series of performances within the city that considered how different codes of public behaviour might be explored through processes of observation, mimicry and choreography, where the spaces of the city were framed as an amphitheatre or stage upon which to perform, hide or even attempt to get lost. Individuals were invited to participate in choreographed events, creating a number of fleeting and partially visible performances throughout the city.

Open City, Slow Walk, part of nottdance07, Nottingham, UK. Video: Iain Finlay.

[5] A slow walking race skirted the perimeter of the market square one day, whilst in another performance on a busy city centre street, a group of seemingly unrelated individuals suddenly came to abrupt standstill and at once all turned to look over their right shoulder towards some undisclosed point of interest. On a separate occasion, a small assembly gradually gathered, remaining immobile at a pedestrian crossing long after they have been given authorization to cross the road.

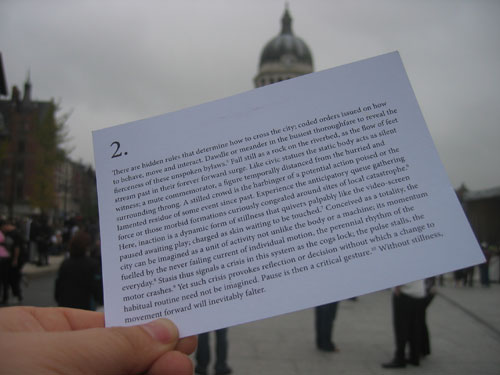

Fig.2. Documentation of Open City postcard originally produced for nottdance07.

Text by Emma Cocker. (Photographer: Emma Cocker).

[6] Six postcards were initially produced in relation to the proposed performances, each of which consisted of a specific time-based instruction written by Open City such as, 'Day or night, take a walk in which you deliberately avoid CCTV cameras' or 'On the high street during rush hour ... suddenly and without warning, stop and remain still for five minutes ... then carry on walking as before'. On the reverse of each postcard, a fragment from my serialized essay elaborated upon the ideas proposed by the instruction. Card (1) addressed the politics of aimless wandering; (2) reflected on the potentiality of stillness; (3) advocated the value of curiosity and of observing one's surroundings; (4) considered the art of following, misdirection and the desire to be led astray; (5) attended to a form of navigation beyond the sense of sight; (6) concerned itself with the palimpsest or archaeology of place, the layers of its lived experience. Having been invited to write the essay, I was keen to produce something that embodied rather than simply commented upon ideas explored within Open City's work, or that operated in performative terms as much as theoretically or imaginatively. Evolved from readings of J.L. Austin's 'speech theory' – which distinguishes between the constative and performative utterance – a performative mode of writing does not simply describe or reproduce the art object or idea, but attempts, like a promise or oath, to enact or perform something through the act of utterance itself.[vi] Instead of my writing being about or simply offering a response to the work of Open City, I wanted to explore how it could be made to shift from the critical or contextual towards the invitational or performative; slipping between description and instruction, or from the textualization of a space or of a performance to the spatialization or performance of a text, of written words.

[7] In addition to the (timed or dated) postcard invitation written by Open City, further instructional suggestions embedded within the writing itself were used to invite people to participate in collective and individual performances. However, the nature of the participation invited often remained ambiguous or deliberately open. One instruction embedded within the essay read:

Close your eyes, and allow your feet to read the streets as though they were Braille, as though they were a musical score. Pay attention to its orchestral patterns and invisible tempo; to the repeated rhythms and staccato breaks, interludes, capricious ruptures, to the melody of wear played out and manifest in heavy palimpsest and notations along the margins. Construct a way of speaking back, as an echo or vibration drawn and performed through your body. Choreograph your reply as a silent eulogy, to others who have walked along this way.[vii]

In this example, an attempt is made to invite a performance at the threshold between the physically experienced and conceptually imagined; between what might be publicly witnessed and what is individually felt. It remains unclear whether a physical response is being solicited or whether the invitation is towards a more imaginative or even invisible performance. In one sense, the postcards produced collaboratively with Open City were pitched in the gap between instruction and invitation, between obligation and provocation, between telling someone to act and asking them to imagine. Those instructions that invited an imaginative performance seemed particularly resonant because there was never any real way of truly telling whether – and how – they had been realized. The instructions embedded within postcard texts called out to as-yet-unknown publics, setting the terms for the possibility of imagined or future assemblies, prospective performances where individuals become temporally united by a rule or instruction that they are collectively – at times invisibly – adhering to. A written text is thus used to create or propose the conditions for moments of 'group togetherness' or shared experience. It sets the scenario for participatory performative actions (in the public realm) or else attempts to unite a disparate yet collective multiplicity of 'readers' who become temporarily bound by the terms of a given text. The specificity of the textual invitation emerges as a particularly potent manifestation of performance writing; a germinal or constitutive speech act capable of creating the conditions wherein an alternative or re-worked model of sociability, participation or even subjectivity might arise.

[8] For Open City, publicly distributed postcards have been used to invite as-yet-unknown publics to participate in collective action. Their instructions are not only intended to breach or break habitual or routine patterns of behaviour, but also attempt to produce a form of collectivity or sociality, formed by strangers deciding to respond to the imperative of the invitation issued. Since this initial project, further postcards have been developed alongside other invitational strategies for producing new forms of collectivity. The instructional form of the postcard has been developed into a series of spoken-word recordings that are listened to on individual iPods or MP3 players, where verbal directions are used to invite specific actions (or non-actions) as part of a live, collective event. Here, different individuals become temporally and momentarily united by a rule or instruction that they are collectively listening to; spoken instructions are used to synchronize the speeds and affectivity of disparate performing bodies. In recent projects, Open City has explored how communities of 'listeners' can be produced through an encounter with a text, where language has become more instructional, operational or even procedural. In 2008, I collaborated with Open City on a practice-based research project entitled, Interrogating New Methods for Public Participation in Site Specific Projects (Japan, 2008) that investigated the affective capacity of different speeds and intensities of individual pedestrian activity in the public realm. In this project, we explored how performed stillness and slowness could operate as tactics for rupturing or disrupting the homogenized flow of authorized and endorsed patterns of public behaviour.[viii]

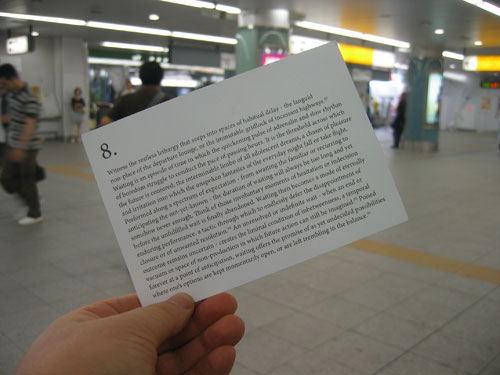

Fig.3. Documentation of Open City postcard originally produced for the dislocate festival,

Yokohama, Japan, 2008. Text by Emma Cocker. (Photographer: Emma Cocker).

[9] Action-research workshops and instructions publicly distributed on two newly produced postcards (No.7 and No.8), were used specifically to invite various individuals to take part in a series of choreographed participatory interventions – journeys, guided walks, assemblies – or to participate in the staging of collective actions that echoed the visual vocabulary of certain stilled social rituals such as memorials or protests. Within this work, we were interested in how the practice of collective stillness and indeed inoperativeness within a performance can be used to challenge – or offer an alternative to – dominant behavioural patterns of the public realm, that are habitually atomizing and utility-oriented, motivated towards a specific individual goal.

[10] Emerging from this research, Open City has since developed a series of audio works for different festival contexts, wherein a group of individuals (often strangers) have been invited to take part in a participatory performance often involving stilling or slowing the body, to create a sense of collective rhythm, the potential of unexpected synchronicities within the public realm.

Fig.4. Documentation of Open City: Still/Walk, public performance in conjunction with

the dislocate festival, Yokohama, Japan, 2008. (Photographer: Emma Cocker).

[11] For example, as part of the dislocate festival (Yokohama, Japan, 2008) a group of individuals were led on a guided walk in which they collectively engaged with a series of spoken instructions listened to individually using iPod or MP3 player technology. The instructions attempted to harmonize or synchronize the movement and speed of individual bodies around moments of slowness, stillness, obstruction and blockage, to produce the possibility of new collective rhythms or 'refrains'. By simultaneously listening to the same recording of instructions, a group of individuals became choreographed towards a collective rhythm; their footsteps slowed or speeded up according to the terms of a seemingly invisible logic. During the Radiator festival 'Exploits in the Wireless City' (Nottingham, UK, 2009) Open City produced a map and a set of recorded instructions that individuals could download onto their own iPods or MP3 players, in advance of a timed performance; a sonically guided walk through Nottingham city centre.[ix] For this performance, Open City invited individuals to assemble anonymously at a specified time and location (3pm, Saturday 17 January 2009, Broadway Media Centre). Potential participants were further instructed, 'When the clock reads 15:05:00 press play – on your MP3 player – and follow the instructions on the recording from that point onwards'. On the day, it was impossible to identify who had assembled for the performance. However, as soon as the instructions were activated, dozens of individuals suddenly stood up and collectively exited the building heading for the city streets. Over the next hour this newly emergent collective were directed through a series of synchronized actions as they traversed the city centre, their bodies intermittently brought into unity before collapsing back into individual rhythms; coaxed into harmony before becoming imperceptible once more amidst the city's crowds.

Fig.5. Documentation of Open City: Guided Walk, public performance as part of the Radiator festival,

'Exploits in the Wireless City', Nottingham, UK, 2009. (Photographer: Julian Hughes).

[12] Group formations were orchestrated around moments of collective stillness, points within the walk where a gathering would assemble and become momentarily stilled, silent. These performances of stillness created a porous or rhizomatic form of community whose edges remained difficult to discern, for unsuspecting passersby became unwittingly included within this new community's constitution in every moment they fell still. During the intervals of invited stillness it became possible to witness the visible evidence – and effects – of a new social configuration existing alongside, or even as an alternative to, the more habitual or typical social assemblages operating within the city.

[13] Open City's performances attempt to draw attention to the habitually endured – or suffered – signs and effects of contemporary experience, through the production or selection of playful, disruptive or even joyful interventions, events and encounters produced between bodies performing in response to an invitational call. Their recent performance-based work has explored the potential within those forms of collective stillness specifically produced in and by contemporary society, reflecting on how they might be (re)inhabited – or appropriated through an artistic practice – as sites of critical action or for generating new ways of operating in the public realm. Performances that encourage dawdling or meandering in places of habitual speed and purposefulness – such as the high street or in the flow of commuter traffic – reveal the fierceness of the city's unspoken bylaws, as the societal pressure towards speed and efficiency becomes momentarily disrupted by the event of deliberate non-production, inaction or the act of doing nothing. The disempowering experience of being controlled – blocked, stopped or restricted – by societal or moral codes and civic laws, is replaced by a minor logic of ambiguous, arbitrary and optional rules (or by the permissions afforded by a particular invitation to act differently). Open City's instructions willfully disrupt and disorganize the language and logic of the major or dominant structure, by re-assembling it into alternative configurations.[x] Individuals are invited to mimic or misuse familiar behavioural patterns witnessed in the public realm, inhabiting their language or codes in a way that playfully transforms and reinvents their use, proposing elasticity or porosity therein. Reinvention emerges as a tactic for breaking down the familiar into a molten state in order to divert its flow, of affecting a change in perception. For Open City, societal rules and behavioural codes are no longer used to hold things in place, but rather become worked until malleable, bent back or folded to reveal other possibilities therein. Unlike the instructions issued by an authority that are often contractual and conditional, Open City's instructional imperative is one of enabling – indeed provoking – other ways of operating critically, differently. Its permissions are often less about containment as liberation and spurring on; they invite that the line is crossed, that expectations are willfully flouted.

[14] Instructions can be nurturing or protective, pedagogical or didactic, authoritative or legislative. Too often there is a sense that they are offered by a 'knowing' authority where they are seen as something that you should do for your own good (thus containing a sense of both threat and promise). Unlike the authoritative instruction, art's invitations remain hopeful rather than assured. The invitation that calls or invokes the as-yet-unknown yes is not like the authoritative power whose permission sanctions only the already known or knowable, but rather it wishes to be surprised. The invitation or proposition is an act of scarification; it unsettles the situation enough to create germinal conditions wherein a new course of action might take root. The invitation that thwarts an easy response creates the spacing of a missed beat; a creative space or opening in which to consider things differently to what they already are. The invitation that hints towards action is a kairotic occasion of opportunity, a moment waiting to be seized. To hint is to offer invitation towards another's response, the leaving of a sufficient gap. The question of how to issue an instruction whilst leaving room for manoeuvre has increasingly become one of critical importance within Open City's work, for there is always the danger that the instructions of an art practice simply end up replacing one set of societal codes or rules within another. Certainly, a precursor to Open City's use of the instructional form can be located within various Fluxus projects from the 1960s and 1970s, for example, both Milan Knizak's Walking Event (1965) and Mieko Shiomi's Shadow Piece (1963) propose actions to be performed in the public realm, whose terms are specific and yet still open to individual interpretation.[xi]

Walking Event

On a busy city avenue, draw a circle about

3m in diameter with chalk on the

sidewalk. Walk around the circle as long

as possible without stopping.

1965

Shadow Piece

Make Shadows – still or moving – of

your body or something else on the road, wall,

floor or anything else.

Catch the shadows by some means.

1963

The instructional or invitational imperative is evident within innumerable Fluxus scores, scripts and proposal pieces, many of which are brought together in the publication An Anthology of Chance Operations (1963), edited by La Monte Young; in the Fluxus Performance Workbook (1990), or more recently in the exhibition Fluxus Scores and Instructions, The Transformative Years: "Make a salad." (2008).[xii] In his essay 'Orders! Conceptual Art's Imperatives', Mike Sperlinger examines the role of instructional practices in bridging between avant-garde performance works of the early 1950s and 1960s and conceptual art, identifying a number of artists – including Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, Douglas Huebler, Yoko Ono – whose mode of operation involved the coercive gesture of an invitation. Exemplified by the work of Yoko Ono, Sperlinger notes how such instructional practices operate as a "series of prompts for the audience to break off from habitual ways of perceiving the world."[xiii] He argues that Ono's instructions function as "thought experiments, where even if a course of action is being suggested it seems more like an invitation to follow a train of thinking."[xiv] Certain propositions by Ono appear like scripts that could be acted out: "Bandage any part of your body. If people ask about it, make a story and tell. If people do not ask about it, draw their attention to it and tell. If people forget about it, reminder them of it and keep telling."[xv] Other invitations remain more enigmatic: "Send the smell of the moon".[xvi]

[15] Whilst many of Ono's instructions were intended for individual enactment (often privately or imaginatively), within certain examples a sense of collective endeavour emerges, where an action or task is proposed for performing with others. In her Let's Piece I, Ono presents a series of invitations for performing the everyday differently, collectively:

Let's Piece I

500 noses are more beautiful than

one nose. Even a telephone no. is more

beautiful if 200 people think of

the same number at the same time.1960 spring

- let 500 people think of the same

telephone number at once for a

minute at a set time.- let everybody in the city think

of the word "yes" at the same time

for 30 seconds. Do it often.- make it the whole world thinking

all at the same time

Ono presents a hypothetical scenario wherein the whole world is invited to participate in a single affirmative act, the event of thinking the word 'yes'. Her invitations do not present the details or logistics of such an occurrence (the when and where of the event); but rather remain propositional 'thought experiments'. For Sperlinger, Ono's invitational yes or let's "attempt to capture the hesitation between speculation ('imagine if ... ') and command"; where they are often issued as "injunction(s) to perform the impossible", in the "modality of wishing".[xvii] He states that, "wishing and hoping are the germinal forms of almost all of her instructions, in a way that cuts across their character as instructions – impossibility is often their precondition."[xviii] However, within Ono's oeuvre there is always the possibility that her invitations could be actualized, if only by an individual or disparate few (rather than by the whole world in unison). In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, do it, Bruce Altshuler reflects on Ono's instructional works arguing that, "An important aspect of such work is the tension between ideation and material realization, for while these pieces seem to be created by being imagined, as instructions for physical action they stake a further claim in the world."[xix]

[16] This willful ambiguity around the execution of the instruction – the lack of certainty around the how, the when and the whether or not it will ever be realized – seems in marked contrast to the way that the instruction is conceived within later conceptual practices. For example, in his Paragraphs on Conceptual Art (1967), Sol LeWitt asserts that, "when an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair."[xx] Here, the use of instructions functions more as a strategy for attempting to deliberately evacuate the subjectively felt from a given action, enabling critical distance, an indifferent and even disinterested position to be (if only momentarily) taken. LeWitt states, "To work with a plan that is pre-set is one way of avoiding subjectivity".[xxi] However, rather than abandoning responsibility by being told what to do, the personal act of decision-making prompted by the invitation of artists such as Ono, reaffirms a sense of agency by allowing the individual to choose whether, in fact, they are interested or perceive any value in the experience that is being offered. For Sperlinger:

The first claim made on us by any instruction is to decide how literally we should follow its terms – with the imaginary extremes being protocol, on the one hand, to be followed to the letter, and pure play on the other, with no suggestion that it is to be actually carried out.[xxii]

In many of the instructional practices identified by both Altshuler and Sperlinger – perhaps exemplified by Ono's work – the idea of chance, situational difference, or the possibility of not being able to predetermine the results in advance seems critical. Here then, the instruction operates less as a command or mandate, as a prompt or trigger which creates the conditions for – or simply opens up the possibility of – behaving differently, without being dogmatic or prescriptive about how this it to be realized, actualized. Ono's respondents are asked to imagine things 'as if', to momentarily suspend the logic of negation, to quell the skeptic's desire to refuse or refute. For artists such as Ono, the invitation is less about provoking a specific or determined form of action, as the catalyst for an open-ended imaginative act. Her invitations operate in the gap between how things are and how they might yet be. Sperlinger suggests that, "because of the ineliminable gap between an order and its execution, instructions always pose the question of plausibility."[xxiii]

[17] Rather than extending the legacy of the Fluxus instruction in general terms, it is the tensions of elements present within Ono's invitational imperative that resonate closest with the intentions of Open City's instruction. An instruction is issued to unknown strangers: there is the suggestion of simultaneous (often imaginative) action; a sense of ambiguity as to whether the invitation is to be acted upon or imagined (the question of plausibility) and (in some instances) the potentiality of a collectivity formed through a single (ethical) decision to participate, by responding to the invitation's call. In developing the invitational format (and intentions) of Open City's instructions, Ono's instructional propositions have been an inescapable point of reference; since they are pitched as purposefully invitational, they set the terms for an action without being didactic or authoritative. The individual's negotiation of the instruction has become increasingly important within Open City's work, where the emphasis has shifted away from simply producing the public spectacle of collective action (akin to the phenomenon of flash mob) towards interrogating the complex of decision-making processes underpinning participation. An invitation issued within the context of an artistic practice can operate as the provocation for non-habitual forms of social behaviour or sociability; moreover, an individual's decision to participate or respond to an artist's invitation (unlike some forms of social instruction) is based on the negotiation of ethical and optional rather than obligatory conditions. To commit to a rule or contract voluntarily or optionally is to make a commitment to something out of choice, by one's own volition. Open City's invitational 'rules' and instructions foreground experimentation and request an ethical rather than obedient engagement. According to philosopher Gilles Deleuze, "it's a matter of optional rules that make existence a work of art, rules at once ethical and aesthetic that constitute ways of existing or styles of life".[xxiv] To make existence into 'a work of art' through the use of optional rules is akin to giving life the quality of a game, whose rules are accepted only as points of critical pressure or leverage against which to work. Rather than being surrendered to with passive and acquiescent obedience, the rules – or instructions – of any game should be approached consciously, modified or dismantled once they begin to stifle action or no longer offer provocation.

[18] It is to this specific lineage or strain of invitational practice that this essay attends, where the issuing of an invitation purposefully asks the recipient to question the plausibility of the request, and then decide how and whether to act in response. The construction, curation or even choreography of a temporary, imagined or even 'invented community' through the use of an invitation issued by an artist, can be witnessed in other examples of contemporary practice, where the instruction or request becomes more overtly used as the rules of the game or as the terms of a contractual proposition. Here, an invitation becomes used to set the terms or establish the constitution of unusual – even arbitrary – categories of belonging or participation, or to interrogate ideas around agency, authorship and authority, where the complex of decision-making processes and social transactions surrounding the issuing of an invitation by the artist become central. For example, artist Sophie Calle's issuing of an invitation is often done in a very immediate way, where the face-to-face request or invitation to enter into a pact of trust, catches the invitee by surprise, prompting a breach in habitual behavioural patterns. In The Sleepers (Les Dormeurs) (1979), Calle invited various friends and unknown strangers to sleep in her bed for eight hours each over the course of a week. The bed becomes the site for further encounter in the project Room with a View, where, as Hal Foster notes:

(L)ying in a bed at the top of the Eiffel Tower, she had this request for the strangers who take turns at her bedside: 'Tell me a story so I won't fall asleep. Maximum Length: 5 minutes. Longer if thrilling. No story. No visit. If your story sends me to sleep, please leave quietly and ask the guard to wake me up'.[xxv]

Alternatively, in the work, Los Angeles, 1984, Calle's spoken request 'Where are the angels?' is issued to solicit the help of a complicit stranger who might offer instructions or a clue for her to follow. In Shizuka Yokomizo's project Dear Stranger (1998 – 2000), it is the residue of an unspoken contractual arrangement that we witness. In this project, the artist sends an anonymous invitation to the homes of random strangers, soliciting them 'and only them' to take part in a curious nocturnal exchange.

Dear Stranger,

[...] I would like to take a photograph of you standing in your front room from the street in the evening. [...] It has to be only you, one person in the room alone [...] I would like you to wear something you always wear at home. [...] I will NOT knock on the door to meet you. We will remain strangers to each other.[xxvi]

Yokomizo requested that each stranger stand motionless by a lighted window; staring out from their home into the inky darkness of the street. In return, she promised to be outside waiting, invisible in the shadows with her camera poised to take their portrait. Yokomizo's Dear Stranger project articulates the multifaceted nature of acquiescence, as an individual voluntarily sacrifices a moment of privacy to the merciless gaze of a camera lens. The work is often discussed as an articulation of the unbridgeable gap between one person and another – there is always something withheld, something incommunicable – however, when presented in exhibition, the photographed individuals appear to have a collective identity, they become 'alike' by their common decision to do something a little out of the ordinary, by their collective act of response. In Adam Chodzko's work, the newspaper ad or classified section serves as the space for the issuing of a textual invitation to strangers. In the project The God Look-Alike Contest (1992-3), Chodzko advertized for people who 'think they look like God' to get in touch with him for an "interesting project". The resulting images bind a disparate group of individuals through their different notions of godliness, and their decision to respond to the artist's ad. Later, in Product Recall (1994), Chodzko set the terms for uniting the owners of a Vivienne Westwood 'Clint Eastwood' jacket. The artist distributed the invitation in style magazines and through fly-posters around Soho, London, and the respondents were assembled for a single event which was recorded on video, evidencing the formation of a fragile collective counter-intuitively constituted on the basis of their initial desire to dress individually. Chodzko's work establishes the terms of ephemeral communities (often creating connections between former strangers) in order to ask: "how can we engage with the existence of others? How else might we relate?" [xxvii] The pages of a newspaper or magazine become the unlikely site for the inauguration of a newly configured social constitution. James Roberts notes that:

Chodzko's main activity is that of a facilitator, creating networks, colliding subcultures and introducing people to offer them a view into spheres that they perhaps had never known existed. Alternatively, he brings people together to try to make sense of their experience and their position in terms of a network or subculture that he has articulated. [xxviii]

[19] These various examples of invitational practices create the constitutional foundations for a nascent social assemblage, formed of individuals momentarily united by and within the shared event of response. The textual invitation thus has potential to operate in disruptive terms, establishing an experimental space or test-bed wherein to rehearse alternative formulations of community or collectivity, produced in and through the act of participation itself. Each artist presents the invitation as a catalyst, which prompts the testing out of other possibilities for being and belonging; their (often playful) interruptions are less about reshaping the world in any permanent sense, as destabilizing its logic a little. Moreover, unlike more typical forms of relational or participatory practice – often predicated on the unquestionable value of participation and conviviality – such invitations request participation in activity that is somewhat unplanned for, awkward or unnerving. The invitation creates an opening – and the making vulnerable of both artist and respondent – as a way of initiating an unknown situation or encounter, the details of which have not yet been wholly defined. Such invitations might be considered a form of kairotic speech act, since they create a brief opportunity within the continuum of everyday life, whose latent potential needs to be actively seized or else lost. Kairos describes a qualitatively different mode of time to that of linear or chronological time (chronos). It is not an abstract measure of time passing but of time ready to be seized: timeliness, the critical time of opportunity where something could happen (or else perhaps be missed). A kairotic form of invitation does not describe an open invitation where anything goes, but signals towards the opening of an invitational encounter, which produces a rupture or aperture in habitual ways of thinking and being, thereby requiring a different mode of inhabitation.

[20] This dual operation of rupture and affirmation is present in a number of projects by collaborative artists FrenchMottershead (Rebecca French and Andrew Mottershead). FrenchMottershead attend to the individual performances of identity and social ritual within different contexts in order to reveal (and then disturb) their grammatical coding, the behavioural etiquette operating therein. [xxix] For these artists – like Calle, Chodzko and Yokomizo – social conventions are not seen as binding or restrictive, but rather become used as raw material through which to create new forms of expression and exchange. Their work pays acute attention to the highly nuanced expectations and behavioural patterns playing out in different environments by different communities, in order to conceive of ways to gently interrupt or disrupt these habitual flows. Through their interventions into or interruptions of the patterns of everyday behaviour, FrenchMottershead reveal the often unseen or unnoticed mechanisms and networks that underpin how a community functions, at the same time as disrupting them just enough for them to be reassembled differently or considered afresh. Their work thus hovers at the interstice of what is real and what is performed or staged. If community describes a specific form of classification or taxonomy through which to group, order – even control – individuals within a single whole, then FrenchMottershead play with these conventions by creating optional, arbitrary or even playfully absurd filters through which to establish connections or bonds between people. The artists observe selected social situations in order to create tailored performative interventions that self-consciously reveal the presence of habitually unnoticed or unquestioned behavioural expectations and protocol at play. Through these tactical interventions the artists attempt to unsettle or destabilize the situation, willfully sensitizing participants to their daily surroundings just enough to invite them to consider other – new or different – ways of operating within its frame. Evident in a number of projects developed by FrenchMottershead over the last decade, this signature strategy of observation and interruption is further put to use within their extended project, SHOPS, where an invitation becomes used specifically for choreographing unexpected configurations of community or belonging.

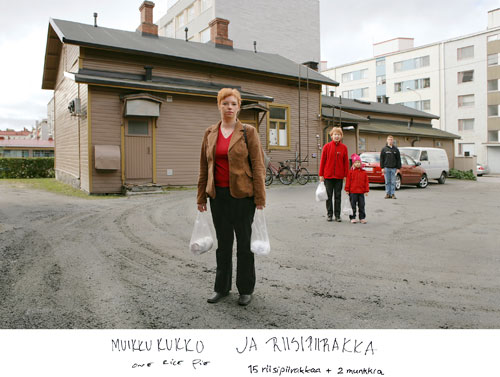

Fig.6. FrenchMottershead, Kalakukkoleipomo Hanna Partanen (Bakery), 10.30 am,

17 September 2005, Kuopio, Finland (Photographer: Pekka Mäkinen).

[21] The origins of the SHOPS project can be traced back to a work made as part of the ANTI festival in Kuopio, Finland (2005) where FrenchMottershead worked with Five Shops to invite their customers to participate in the live event of a ritualized group photograph, where the request itself was performed by the shopkeeper as a whisper or surreptitiously stamped on the back of each till receipt. Since then, the artists have negotiated a series of international residencies in other cities in Brazil, China, Romania, Turkey and the UK to establish similar collaborations, produce further group photographs. Each installment or iteration of the project seems to follow a similar pattern: first – the identification of a handful of appropriate shops (often independent, local, a little special); second – close collaboration with each shopkeeper to devise a method of invitation appropriate to their customers and shop; third – the issuing of the invitation itself followed by a period of tentative anticipation; fourth – a live event (the performative production of a collective portrait at the shop); fifth – the ceremonial exhibition of the resulting photograph back at the location of its creation. [xxx]

Fig.7. FrenchMottershead, Shops Slideshow: Documentation (DV 2:52 mins.) 2006

(Photographer: Alexandra Wolkowicz).

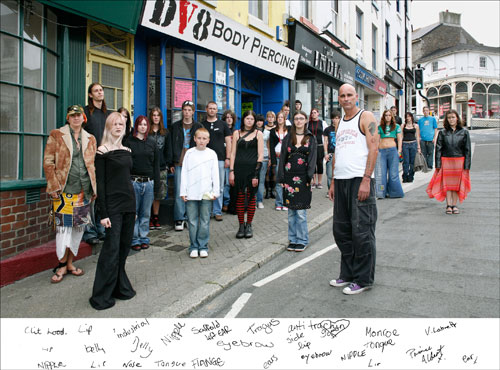

[22] Individually, the photographs record the gathering of a group of persons together in one place, a singular social assemblage united through a common connection or bond, the act of shopping. What unites the disparate individuals encountered within the SHOPS project is that they have all voluntarily opted to participate in their chosen community. Unlike those rather more fixed and enforced societal categories of community based on already defined geographical, social or economic criteria, the project's social groupings are constituted through a process of self-selection, on an individual's decision to have a piercing or buy a hat. Moreover, beyond the act of purchasing goods, the individuals have further elected to participate in a social ritual orchestrated by the artists. As such, the photographs do not simply document the customers of a selected shop on a given day, but are group portraits of those individuals who curiously responded to an invitation.

Fig.8. FrenchMottershead, DV8 Body Piercing, 1.45 pm, 19 August 2006, Penzance, UK

(Photographer: Steve Tanner).

[23] The use of invitations or instructions is a device often used by FrenchMottershead for activating public participation within their work, for gently provoking or prompting unexpected forms of social behaviour. [xxxi] With its etymological origins in the French terms etiquette (prescribed behavior) and éstiquette (a label or ticket), derivations of the term etiquette have also been used to describe small cards written or printed with instructions, which offered guidance on how to behave properly at court. [xxxii] Inverting this logic, FrenchMottershead's printed or spoken instructions work against the expectations of social etiquette, granting the individual recipient permission to behave against the grain, contrary to habit or routine. Within the SHOPS project it was the shopkeepers who issued the invitation, asking their customers to participate in the making of a ritualized group portrait. Individuals are not photographed whilst shopping, but return instead to participate in the ceremonial inauguration of a new community produced through the lens of the camera.

Fig.9. FrenchMottershead, Casa Preto Velho (Religious Articles), 3 pm, 17 January 2008,

Salvador, Bahia, Brazil (Photographers: Rebecca French and Andrew Mottershead).

[24] Collectively returning to the site of a previous relational or social exchange (between shopper and shopkeeper), the gathering of individuals perform a strange reunion; the meeting of a community who may never have before acknowledged its own constitution, like the awkward assembly of wedding guests for whom the only common connection is the bride or groom. Separated from the habitual routines of everyday life, these individuals are like initiates at the threshold of a nascent communion; each photograph somehow marking the liminal site of a rite of passage, the swearing in of a newly elected. During the intervals of photographic stillness it becomes possible to witness a new social configuration existing alongside, or even as an alternative to, the more habitual or typical social groups operating within contemporary culture. The portraits thus make visible a particular form of social bond – between the shop and its community – whilst also attesting to the honoring of a contractual bond or promise, a commitment to participate made between strangers.

[25] Within the work of FrenchMottershead (as with that of Open City) the invitation operates as a tool for breaking down habitual patterns of behaviour (and of sociality) whilst establishing the conditions for alternative forms of interaction. The invitation functions as a kind of catalyst, producing a breach into which a new or unexpected mode of behaviour or action is called. Practices such as that of FrenchMottershead and Open City, appropriate the vocabulary and syntax of various social situations found or encountered, recombining them through invention and improvisation to produce new kinds of social assemblage. Rather than a form of socially engaged practice or collaboration that involves the participation – and often proposed empowerment – of an already defined or constituted community, such practices instead actively produce propositional and experimental social assemblages, based on criteria that are playfully optional and often temporary, rather like the rules of a game. Here perhaps, the logic of 'new genre public art' or participatory practice collides and reconnects with the traditions of artistic assemblage or even of postproduction, the borrowing and reassembly of existing cultural and social formations into new compositions or refrains. [xxxiii] In 1961, William Seitz identified assemblage as a specific form of art practice; the juxtaposition and reassembly of arbitrary and everyday "preformed natural or manufactured materials, objects, or fragments not intended as art materials" into fragile and often haphazard arrangements. [xxxiv] For Seitz, the precarious or contingent creations produced through acts of assemblage often appeared underpinned by "the need of certain artists to defy and obliterate accepted categories"; their willed attempt to rupture or challenge existing definitions and systems of classification. [xxxv] The social assemblages produced by the artists' invitations discussed in this essay similarly evade or blur the terms of existing systems of classification or capture. The terms of their invitation (like that of the party invitation) is always time-bound, its proposition one of a momentary breach or break in habitual ways of operating, a lapse in the logic of normative behavioural codes. The communities or collectivities that are assembled are never lasting, but rather they exist as temporary configurations or as propositions.

[26] Taking the example of Open City's use of instructions as a starting point, this essay has thus far considered different strategies within artistic practice, whereby an invitation becomes used to curate and choreograph a form of collectivity or community, differently to those configurations habitually encountered within contemporary culture. In this sense, projects such as Open City operate as an embodied, experiential test site, wherein broader contemporary debates relating to community, participation and social belonging might become exercised or rehearsed. There has been an attempt within recent contemporary art theory to investigate how certain art practices present opportunities for the 'performing' of subjectivities, collectivities and cultural identities beyond the reach and limitations of habitually designated social configurations or groupings; in turn, questioning what it means to take part in culture beyond the roles that culture typically affords. Recent theorizations focusing on those models of participation and collectivity specifically produced in and through art-practice have typically challenged the idea of community as a fixed and definitive marker of social identification and belonging, re-conceiving it as a time-bound, constructed and highly contingent social assemblage. For example, in Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (2004), Grant Kester explores various art practices that "share a concern with the creative facilitation of dialogue and exchange," [xxxvi] where conversation is reframed as "an active, generative process that can help us speak and imagine beyond the limits of fixed identities, official discourse, and the perceived inevitability of partisan political conflict". [xxxvii] Kester uses the term 'dialogic aesthetic' or 'dialogic encounter' to describe art practices that "unfold through a process of performative interaction," [xxxviii] whose mode of production is one of sociability or relational communication. Alternatively, in One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (2004), Miwon Kwon attempts to articulate a shift from site to community within new genre public art, coining the term 'temporary invented community' to describe those specific social configurations that are "newly constituted and rendered operational through the coordination of the art work itself," [xxxix] formed "around a set of collective activities and/or communal events as defined by the artist." [xl] Such communities, she asserts, are both projective and provisional, always "performing its own coming together and coming apart as a necessarily incomplete modeling or working-out of a collective social process. Here, a coherent representation of the group's identity is always out of grasp." [xli]

[27] Theorist Irit Rogoff explores a similar "emergent collectivity" – those "emergent possibilities for the exchange of shared perspectives or insights or subjectivities" – made possible through the encounter within art practice, within her essay, WE: Collectivities, Mutualities, Participations (2004). [xlii] She points to how "performative collectivity, one that is produced in the very act of being together in the same space and compelled by similar edicts, might just alert us to a form of mutuality which cannot be recognized in the normative modes of shared beliefs, interests or kinship." [xliii] In these terms, invitational art practices foster a specific 'form of mutuality' or 'performative collectivity', emerging through the shared decision of disparate individuals to respond to the demands of the invitation's 'edict'. The notion of a temporary collectivity formed by strangers making a decision to respond to an invitation which required them behave or perform a situation differently, or against habitual expectation, seems particularly charged. In the more recent exhibition, If We Can't Get it Together: Artists rethinking the (mal)function of communities, curated by Nina Möntmann, the idea of 'community' came under further scrutiny, the premise of the exhibition itself asserting a need for radical renewal and rejuvenation of the term. Bringing together work by Shaina Anand, Egle Budvytyte, Kajsa Dahlberg, Hadley + Maxwell, Luis Jacob, Hassan Khan, Emily Roysdon and Haegue Yang, the exhibition explored in part, "tension(s) between the desire to identify with a group and ambivalence about collective affiliation." [xliv] Möntmann's subsequently edited publication, New Communities, continues the critical concerns of the exhibition to further address "the emergence of temporary and experimental new communities in art and society that refuse to function as an easily manipulated mass united by a common identity"; exploring "ideas about how to position yourself as an individual, how to conceive communal spaces and to what extent communities inform the quality of public space". [xlv]

[28] These various theoretical enquiries signal towards the capacity of certain art practices to intervene in and challenge how the public realm is activated and navigated by producing what Michael Warner calls 'counter-publics'; new social formations developed differently to the discourses and interests of the official public sphere, for rehearsing and testing alternative – ethical, political, critical – forms of sociability and togetherness. [xlvi] Kwon's term 'temporary invented community', Rogoff's 'performing collectivities' and even Möntmann's 'new communities' might describe the temporary relationships, connections and intensities that bind together diverse individuals within the specific space-time of a participatory performance. However, rather than reflecting broadly on how art practice can produce collectivities or mutualities through the encounters offered therein, this essay has focused on practices that utilize the specificity of an invitation to do so. In the examples of practice discussed, an invitation is used to curate or choreograph a form of temporary collectivity within the public realm; its social assemblages are necessarily fleeting and impermanent. Whilst theorists such as Kwon appear to lament the limited life span of 'temporary invented communities', which she says are always "dependent on the art project for their operation as well as their reason for being", this impermanence might in fact be considered as the source of their critical strength. [xlvii] The invitation always has a quality of 'futurity', creating the conditions for an ever-emergent community that is always in progress, ever responding and responsive. The 'temporary invented communities' produced through the dynamic of invitation and response are never lasting configurations, but require continual rehearsal and reassembly. These communities or collectivities produced through (art) practice willfully resist being fully aggregated back into or encoded within the terms of the dominant social structure, remaining forever receptive to the contingent conditions of the next invitational call.

Notes

[i] This list of 'instructions' or 'invitations' are examples of the kind issued by the art project Open City, however, the wording and numbering varies here from how they would be encountered within the project. See Fig.1 for an indication of the visual format of Open City's postcard instructions.

[ii] I would like to thank Open City, especially Andrew Brown and Katie Doubleday, for the provocation offered by their practice, and for the opportunity of collaborating with them.

[iii] This essay develops a paper presented at the Language, Writing and Site seminar, which was originally commissioned by ANTI, the festival of performance and site-specificity in Kuopio, Finland, 29th September 2010.

[iv] More about the wider context of my practice can be found at http://not-yet-there.blogspot.com/

[v] For example, see Emma Cocker, 'Desiring to be Led Astray', Papers of Surrealism, Issue 6 Autumn 2007, available online at «http://www.surrealismcentre.ac.uk/papersofsurrealism/journal6/acrobat%20files/articles/cockerpdf.pdf» (accessed on 31 December 2010) or 'The Art of Misdirection', Dialogue, Issue 5, Burning Public Art, available at «http://www.axisweb.org/dlfull.aspx?essayid=70» (accessed on 31 December 2010).

[vi] See J.L. Austin, (1962), How to Do Things with Words, New York: Oxford University Press.

[vii] The text is an extract from Postcard No.5, text by Emma Cocker, produced in collaboration with Open City, 2007.

[viii] The notion of collective stillness is interrogated through the prism of the Deleuzian-Spinozist concept of 'bodies in agreement' in Emma Cocker, 'Performing Stillness: Community in Waiting' in Stillness in a Mobile World, (eds.) David Bissell and Gillian Fuller, (Routledge, 2011).

[ix] The audio download for Open City's walk is available at http://www.radiator-festival.org/downloads. (Accessed on 31 December 2010).

[x] Here, following Deleuze and Guattari's notion of a minor practice, the coded order of the dominant structure is deterritorialized before being 'appropriated for strange and minor uses.' See G.Deleuze and F.Guattari, 'What is a Minor Literature', Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, trans. Dana Polan, London and Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986, p.17.

[xi] Examples cited from The Fluxus Performance Workbook, (eds.) Ken Friedman, Owen Smith and Lauren Sawchyn, re-published as a Performance Research e-publication, 2002, available online at «http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/fluxusworkbook.pdf». (Accessed 31 December 2010). For Milan Knizak's Walking Event (1965) see p.64, for Mieko Shiomi's Shadow Piece (1963) see p.94.

[xii] See An Anthology of Chance Operations, (ed.), La Monte Young, (first edition published La Monte Young & Jackson Mac Low,1963). The exhibition Fluxus Scores and Instructions, The Transformative Years: "Make a salad." took place at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Roskilde, Denmark (June 7 – September 21, 2008). Fluxus Scores and Instructions, The Transformative Years: "Make a salad." was accompanied by the exhibition catalogue of the same title, edited by John Hendricks, with Marianne Bech and Media Farzin, (Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009).

[xiii] Mike Sperlinger, 'Orders! Conceptual Art's Imperatives', in Afterthought: new writing on contemporary art, (Rachmaninoff, 2005), p.11.

[xiv] Sperlinger, 'Orders!', p.9.

[xv] The instruction 'Conversation Piece (or Crutch Piece)' can be found in Yoko Ono, Grapefruit, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2000), unpaginated. Grapefruit was originally published in 1964.

[xvi] The instruction 'Smell Piece I' can also be found in Yoko Ono's Grapefruit, unpaginated.

[xvii] Sperlinger, 'Orders!', p.9.

[xviii] Sperlinger, 'Orders!', p.11.

[xix] Bruce Altshuler, 'Art by Instruction and the prehistory of do it', in do it, ex. cat. (New York: Independent Curators Incorporated, 1997), p.24. The catalogue was published in conjunction with the exhibition do it, conceived and curated by Hans-Ulrich Obrist.

[xx] Sol LeWitt, 'Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,' in Art in Theory, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (London: Blackwell, 1992), 834. Originally published in Artforum, Vol.5, No.10 (Summer 1967), 79-83. See also Sol LeWitt, 'Serial Project No.1 (ABCD),' Aspen Magazine, 5–6 (1966), not paginated, reprinted in Sol LeWitt, ed. Alicia Legg exh. cat (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1978), 170–71 and also in Minimalism, ed. James Meyer (London, New York: Phaidon, 2000), 226–227

[xxi] Sol LeWitt,'Paragraphs on Conceptual Art'.

[xxii] Sperlinger, 'Orders!', p.8.

[xxiii] Sperlinger, 'Orders!', p.12.

[xxiv] Gilles Deleuze, 'Life as a Work of Art', Negotiations: 1972-1990, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), p.98.

[xxv] Hal Foster, 'Paper Tigress', October, Spring 2006, No. 116, p.50.

[xxvi] Excerpt from Shizuka Yokomizo's instruction from the project, Dear Stranger.

[xxvii] From a statement by Adam Chodzko available at the artist's website, http://www.adamchodzko.com/ (Accessed on 3 November 2010).

[xxviii] James Roberts, 'Adult Fun', Frieze, Issue 31, November-December, 1996. Available at «http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/adult_fun», (accessed on 31 December 2010).

[xxix] See also Emma Cocker, 'Social Assemblage', in SHOPS, People and Places (Sheffield: Site Gallery, 2010).

[xxx] A slideshow of images and documentation from FrenchMottershead's SHOPS project in Kuopio (Finland), Penzance, Liverpool and Norwich (all UK) can be found online at «http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uYYjjQcUPg0». Accessed on 31 December 2010.

[xxxi] See FrenchMottershead's Club Class (2006 – ongoing) or The People Series (2003 – ongoing).

[xxxii] This definition of etiquette is by historian, Douglas Harper, in the online Etymology Dictionary. See «http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/etiquette» (Accessed: 6 January 2010).

[xxxiii] See Suzanne Lacy, (ed.) Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art, (1994) and Nicholas Bourriaud, Postproduction (Lukas and Sternberg, 2002).

[xxxiv] William Seitz, The Art of Assemblage, (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961), p.6.

[xxxv] Seitz, The Art of Assemblage, p.92.

[xxxvi] Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (University of California Press, 2004), p.8.

[xxxvii] Kester, Conversation Pieces, p.8.

[xxxviii] Kester, Conversation Pieces, p.10

[xxxix] Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity, (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press, 2004), p.126.

[xl] Kwon, One Place After Another, p.126.

[xli] Kwon, One Place After Another, p.154.

[xlii] Irit Rogoff's WE: Collectivities, Mutualities, Participations (2004) is available at «http://theater.kein.org/node/95». Accessed on 31 December 2010.

[xliii] Rogoff, WE: Collectivities, Mutualities, Participations, unpaginated.

[xliv] From exhibition description accessed on 3rd November 2010, at «http://www.thepowerplant.org/exhibitions/winter0809/together/artists_card.html».

[xlv] From Nina Möntmann's, Lecture on Community and Collectivity, International Academy of Art Palestine, 8th March, 2008.

[xlvi] See Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics, (Zone Books, 2005).

[xlvii] Kwon, One Place After Another, p.130.