Story Networks: A Theory of Narrative and Mass-Collaboration

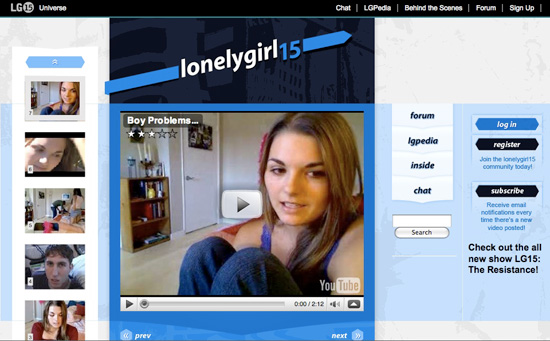

Courtney Hopf

University of California, Davis

The Rise of the Internet Serial

[1] In July of 2006, a 16-year-old girl named Bree set the online community buzzing with her YouTube videos posted under the name of "Lonelygirl15." Bree's videos followed the typical video blog or "vlog" format: simply speaking into her webcam about whatever was on her mind, Bree captivated viewers with her youthful quirkiness. Her posts ran the gamut from silly to serious; one day she would be assessing her complicated relationship with her best friend Daniel, the next she would post a humorous account of Pluto's loss of its planetary title or perform a puppet show with her stuffed animals. Bree was homeschooled by strict, protective parents, so the webcam in her room was her link to the outside world, and that world was taking notice. Soon blogs all over the Internet were talking about the pretty, endearing girl on YouTube. However, it quickly became clear that the fascination surrounding her was not the usual vague, passing interest one associates with forwarded emails and shared links, but detective work. A web-based dialogue broke out between YouTube commenters, gamers, and bloggers because to them, Bree was suspect. Her videos were too tight, too well-edited, too lacking in pixilation. Within weeks the story broke, and the Internet hounds were proven right: Bree didn't exist.

[2] Instead, she was recent acting school graduate Jessica Lee Rose, and her story was the invention of two fledgling California writers, Miles Beckett and Mesh Flinders. In the months that followed, they continued her story as though no such revelation had occurred, and though many who had followed her vlogs felt betrayed, her core audience remained faithful and a massive new one joined the frenzy. Lonelygirl15 was a new kind of serial entertainment, and it was officially a hit. Most interesting is the fact that, though the story had broken, the spell had not. Thousands of fans came together to maintain this fiction, to participate in it, and - most crucially - to take possession of it. A Lonelygirl15 "fansite" appeared (it was actually run by the creators, but designed as a fan website to maintain the fiction), and viewers quickly realized that any "response" videos they created would appear on the site alongside the official series videos. They immediately began participating, posting videos as themselves or as made-up characters, but always playing along with the established storyworld. At first they merely offered advice and support to the characters and each other, but it wasn't long before they discovered that their contributions could actually affect the course of the plot. Soon after, they began to latch onto plot holes and to build entire subplots out of statements and events from the official videos, [1] and thus there began a proliferation of paratexts set in the same universe - the "Breeniverse," as it came to be called.

[3] Lonelygirl15 occupies a privileged space in the annals of Internet history, because like the Lumière brothers' startling cinematic train [2] or Orson Welles' famous War of the Worlds radio broadcast, it had an effect that no narrative creation in the same medium can ever have again. It caused large numbers of people to react to a fictional construction - indeed a plot based around recognizable narrative tropes and genres - as though it was a genuine part of their physical reality. However, unlike the Lumières' film or Welles' broadcast, the revelation of the truth did not stop audiences from maintaining the fiction. Rather than turn their backs, the fans of Lonelygirl became participants in a unique experiment in multi-user storytelling, a vast narrative network, encompassing video blogs, chat rooms, message boards, and even real world interactions. In short, they became a story network.

[4] I derive the concept of the "story network" by hybridizing the functions performed by social networks and storyworlds, two terms that have entered common parlance in recent years. Social networking is all too familiar to the Facebook and MySpace users of the early 21st Century, [3] and refers broadly to the Internet-based programs used by many today for personal and professional interaction. The main purpose of these sites is generally not to initiate friendships or acquire new acquaintances, as the term "networking" implies, but rather to allow users to make visible and categorize their previously established friendship networks (Boyd and Ellison). This model of friendship and acquaintance provides the mass-connectivity required to build what I am calling a story network. "Storyworlds," in turn, furnish networks with the narrativizing process in which members of a social network participate. The concept of the storyworld has gathered weight in recent years among literary and media theorists, as narratologists and others attempt to grapple with the effects of digital and mass media upon narrative theory. The term helps to make narrative "transmedial" or "cross-platform" in an era when a single story can span across novels, television, film, the Internet and a variety of real world outlets. "Story networks," thus, are storyworlds that are built with the cooperation and collaboration of large numbers of users or participants, and the process piggybacks on the social networks people form, allowing them to jointly imagine a world and a narrative. We might also call them the narrative arm of "remix culture," as described by theorist Lawrence Lessig, in which the so-called "consumers" of a story are actively involved as creators, and the initial creators see this as vital to the process (Lessig 2008). Unlike the visual, textual, or musical "objects" or "tokens of culture" Lessig focuses upon, however, the raw materials of a story network are cognitive narrative components. Plots, themes, characters, settings - these are what participants in a story network utilize to make their contribution as they create original videos and texts.

[5] Little work has been done to examine the collective in relation to narrative, and perhaps for good reason. Many long-established narratological tools and theories are unsuited for describing narratives that are built through processes of mass collaboration. Focusing specifically on massively-authored Internet narratives, this article proposes methods of inquiry that can help us describe the complicated process of interaction and collaboration experienced by its creators and participants. By examining the development of collaborative digital storytelling in recent decades - from usenet groups and multi-user dungeons (MUDs) to alternate reality games and web serials like Lonelygirl15 - this article delineates the consequences of changing technologies on mass-collaboration, and ultimately suggests that such technologies blur the lines between fiction and reality and effectively allow users to experience their lives as narrative.

Immersion, Interactivity, and the Problem of Space

[6] The interpretive difficulty posed by Internet story networks is fundamentally a problem of defining the borders of narrative space, because the digital has become an omnipresent mediator of the real. One of the pivotal elements of web serials like Lonelygirl15 is that they collapse boundaries between reality and fiction by introducing characters who possess the same online, digitally-mediated identities that every user possesses: MySpace and Facebook pages, YouTube accounts, email addresses, message board logins, and chat room ID's. Participants interact with these characters on the same level they would with any online friend, effectively erasing diegetic boundaries. This erasure forces us to reconsider long-held notions regarding what it means to be "immersed" in a narrative. Indeed, immersion is one of the fundamental paradigms of interactivity theory, and it unavoidably ties the process of narrative interaction with spatial awareness.

[7] For critics looking at interactivity, a narrative is deemed successful when the medium becomes transparent. The story is experienced with immediacy, and the boundaries between the representation and the audience's cognitive experience disappear. In addition to a spatializing move, this concept is also almost universally applied to texts through metaphors of transport: immersion is judged to be achieved when a reader or audience goes "into" another space. Janet Murray describes the immersive experience as a "visit" or "jumping in" to another world (106), and Michael Mateas stresses that "the player does not sit above the story, watching it as in a simulation, but is immersed in the story" (20, italics in original). Sherry Turkle, similarly, cites the text-based MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons) of the 1990's as spaces you "move into" (189), and Marie-Laure Ryan notes that "for immersion to take place, the text must offer an expanse to be immersed within" (90, my italics).

[8] The semantics of these assertions describe immersive narratives that are always cognitively elsewhere, environments that we inhabit wholly but temporarily through an imaginative process. However, with regard to the collapsed boundaries of Internet story networks, it is clear that this metaphor of transport does not always apply. More specifically, with these particular narratives the interface is always already transparent because the users have no need to go "elsewhere" (cognitively or otherwise) for their immersive experience. Instead, the story colonizes the digital spaces inhabited by the user in his or her daily life. It is this colonization that suggests we are in need of a new vocabulary for imagining immersive environments. [4] Mark Nunes perhaps best clarified the conundrum when he stated, "The problem of cyberspace is marked by our difficulty in reducing space to either materiality or metaphor" (11). As cyberspace encroaches on lived space, this difficulty is marked by the ways in which digital users are conflating lived experience with narrative performance.

[9] In consequence, I contend that this desire to incorporate narrative into everyday reality is a function and result of a specifically postmodern construction of spatiality driven by digital technology. Contemporary interaction with "reality" entertainment (and the semantic minefield that entails), mass media across platforms, and the kind of socializing enabled by the Internet is allowing us to imagine the everyday world as part of a fictional construct. As early as the mid-nineties, Edward W. Soja provided the beginnings of a model for how we might locate this postmodern/performative consciousness in his book Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (1996). Though written before the Internet explosion, Soja anticipated the theoretical problems of cyberspace and virtuality that would soon emerge from literary fiction into our everyday experience. Like Mark Nunes, Soja is heavily indebted to Henri Lefebvre, continuing Lefebvre's project of undermining the reductive effects of theoretical binarism. Soja defines what he calls the "thirdspace" of meaning, "an-Other option" that is both outside binary possibilities and derived from them.

Thirding introduces a critical 'other-than' choice that speaks and critiques through its otherness. That is to say, it does not derive simply from an additive combination of its binary antecedents but rather from a disordering, a deconstruction, and tentative reconstitution of their presumed totalization producing an open alternative that is both similar and strikingly different (61).

Drawing on Lefebvre's philosophy, Soja suggests that an important "thirding" is the addition of spatiality to the historicality/sociality dualism that has guided much of western philosophical thought. Similarly, Nunes has worked to collapse these categories, describing cyberspace through a trinity that is "material, conceptual, and experiential...it is mapped by conceptual structures, material forms, and lived practice" (43). Drawing on these ideas with regard to the spatiality of collaborative Internet storytelling, I contend that the "space" entered by participants in such narratives is both "real-and-imagined," both "material, conceptual and experiential," a space that somehow encompasses both the physical world in which a user types on a keyboard or edits their video blog and the intangible digital world that connects, distributes and processes. The space of this narrative is neither one nor the other, but a thirdspace that requires both to exist.

[10] When narrative is defined as a process within a growing, changing world or universe, it can also occupy a variety of textual and visual media, and indeed some of the most massively-authored narratives to date were realized with the benefit of digital technology and the high-speed connectivity the Internet provides. This is not to say, however, that collaborative interactions resembling story networks are a new phenomenon solely enabled by the Internet Age. On the contrary, a story network forms wherever there is mass collaboration, and while my concept of the story network is derived specifically from digital innovations, it can be deployed across a variety of pre-digital narratives to help us re-imagine narrative in terms of the collective. [5]

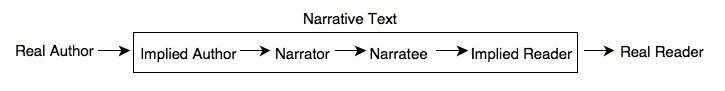

[11] Historically, and at its most minimal, narrative was viewed as a verbal act or utterance in which "someone tells someone else that something happened" (Smith, 232), a useful formulation because, as Barbara Hernstein Smith notes, it engages narrative as a social discourse, does not restrict it to written text, and structures it as an act. At the same time, this perspective can be limiting because it still presents narrative in terms of a binary, in this case through the structure of a narrator and narratee, or a sender and a receiver. Classical narratology is constructed around these dualisms, many of which derive from narratology's roots in structuralism and formalism. For generations that binary has been fundamentally sound, as it is widely accepted that narrative occurs on two levels: the content of a story and how that content is presented - variously described as story and discourse, fabula and sjuzhet, histoire and récit, and a variety of complications based around these initial formulations. Over time, a widely-accepted "model of narrative communication" has developed, which generally looks like this:

[12] Though various complications of classical narratology have been proposed, they maintain two important distinctions. Story and discourse, regardless of how they become fragmented, remain the two levels that define narrative. More importantly, as the arrows and box of the diagram testify, authors and readers are perpetually separate, occupying opposite ends of a teleological line that runs from creator to consumer. As the definition of narrative has broadened to include storyworlds, little work has been done to conceptualize what it would mean for that world to be created by multiple minds, and for the "senders" of a narrative to be influenced by the "receivers" of it. When considering a story network, then, that single line of communication must be reconceived as a series of circles or feedback loops, emphasizing how "readers" influence narrative creation as much as "authors."

[13] Of course, there is still a point of origin - an initial narrative is proposed by an author or set of authors - in the case of Lonelygirl15 we might consider this the original series of videos that appeared before the YouTube audience was aware they were fictional. These initial offerings do follow a simple one-to-the-other trajectory. However, as readers or participants take up the different narrative strands and begin to contribute to the growing storyworld, or even just comment on individual videos, they affect both each other and the original creators, and the map of narrative communication shifts rapidly from a straight line to a web or cloud. However, I contend that the network best implies the data that moves across this web of conversations and creations. The participants in this network simultaneously negotiate roles as author, implied (performed) author, fictional character, reader, implied (ideal) reader, and critic, and all of these roles can exist in both the real world and the fictional one. In short, it is not just the boundaries of reality and fiction that are collapsed, but the historically rigid confines separating who gets to create art and who gets to consume it.

[14] As models of mass-collaborative creation, story networks inherently invoke a narrative "thirding" because the process of production or creation becomes as valid a level as story and discourse. The multiplicity of authors undermines the traditional sender/receiver (author/reader) model of narrative, and the conversations and interactions amongst those authors itself becomes "readable" in the final product. I call this third level the "dynamic paratextual environment" or DPE, and it includes all forms of textual or visual production that comment on the "main" narrative or enable communication between the creators of that narrative. This term emphasizes how the "conversations" that surround a mass-collaborative text are continually in flux and even exhibit conflicting agendas or agencies. It also notes that the data for reading these conversations is derived from paratextual information - letters written amongst authors and editors, comment and message board threads on the Internet, and behind-the-scenes features on DVDs, to name a few. Finally, the DPE is, like any virtual space, both cognitive and spatial, real and imagined. Whether its data is contained in physical objects like sheets of paper or digital spaces like the Internet, its emphasis is the transmission of that data, the spaces between sender and receiver, and where and how those communications intersect. With the rise of Internet storytelling, the availability of such data has grown exponentially.

Web serials, ARGs and their Precursors

[15] Given the ubiquity of videos on the Internet today, it can be surprising to look back and see how quickly it became a common standard in online content. Powerhouse website YouTube first launched in 2005, just as digital video cameras and consumer editing software were becoming more affordable, and the technology to support web video became standard on all personal computers. In a short time, traditional blogging was supplemented with "vlogging" - video blogs - as many thousands of people, usually young people, explored this new way of expressing themselves on the web. Personal diaries, how-to videos, practical jokes, and amateur performances quickly inflated YouTube's ranks, and as the site celebrated its fifth anniversary in May 2010, it reported streaming an astonishing 2 billion videos every day (Parfeni). Amongst this proliferation of video content, a trend toward narrative fiction emerged in the form of web serials.

[16] Web serials can consist of hundreds of short videos and usually appear as 3- to 5-minute "webisodes." They can be released on video-hosting websites like YouTube or through the creator's own domain. Most web serials comment metatextually on their medium by featuring characters who are savvy Internet users. Award-winning serial The Guild, for example, is about a group of teenagers who play together as a team in a Massively Multi-Player Online Role-Playing Game (or MMORPG). In Quarterlife, which featured a group of 20-somethings trying to find their place in the world, each character maintained video blogs that appeared both within the series and as supplements to the main storyline. And Lonelygirl15, as I have described, began as a seemingly "real" video blog on YouTube and was told entirely through vlog posts made by the characters. The trend has been to feature interactivity in the serials by engaging the characters in the same activities as the viewers - blogging, commenting, posting messages. They speak to these audiences because they speak as them, and this serialized reflecting of user experience is one of the many ways in which the physical world collapses into the fictional one.

[17] However, seriality has long been understood as a process that possesses a boundary-collapsing function. Since the rise of the mass reading public in the nineteenth century, serial forms have been not just a dominant form of entertainment, but often an early mode through which new media forms will enact their storytelling functions. This is due to numerous factors, among them economics and technology (short films were less expensive to produce than features, serialized novels in magazines more affordable to the public than entire books, and so forth), but also, as theorists of seriality have asserted, the serial form is a surefire way to hook an audience. [6] Charles Dickens famously exploited the power of the serial cliffhanger, accomplishing the task so well that, as the story goes, mayhem ensued as readers stormed New York City piers in anticipation of the final installment of The Old Curiosity Shop, shouting frantically to arriving travelers from Britain, "Is Little Nell alive?"

[18] As Dickens well knew, and Jennifer Hayward notes, serialization "essentially creates the demand it then feeds: the desire to find out 'what happens next' can only be satisfied by buying, listening to, or viewing the next installment" (3). The result of this cycle of frustrated and satisfied expectation means that serial audiences become adept at residing in and among the stories they follow, and easily slipping from their own world into the storyworld and back again. In The Victorian Serial, Linda K. Hughes and Michael Lund discuss how the extended time between serial installments allowed the world of the serial to develop alongside the real world of the readers, and encouraged them to form more of a bond with the fictional world: "reading did not occur in an enclosed realm of contemplation possible with a single-volume text...rather...[it] was engaged much more within the busy context of everyday life" (8). As such, the blurring of reality and fiction I emphasize with regard to Internet-based story networks is simply a logical extension of the serial worlds of the Victorian era.

[19] Web serials lack the extensive time between installments that characterized Victorian seriality, or the comic book seriality of the 20th Century, or even the week-to-week anticipation experienced by contemporary television viewers - Lonelygirl15 put out webisodes five days a week. However, this consistency served to have the same effect upon audiences that long gaps once did: the "Breeniverse" was always there, a persistent world in which time continued to flow even when users weren't watching. Further, in keeping with the idea that the people creating videos were just regular teenagers dealing with extraordinary events, there was no set time of day during which the daily videos could be expected to be posted, so particularly fixated fans would check the website throughout their waking hours, hoping to catch the video as soon as it appeared. Additionally, as the story network grew and fan-created content became just as integral to the storyworld as "official" content, the sense of the "persistent" world grew even more for the participants. They interacted constantly with each other and the characters through message boards and chats, completely erasing the line between what constituted their "real" online lives and their fictional ones.

[20] Web serials that I define as story networks (as opposed to serialized shows that are just released on the Internet instead of television) will generally have an Alternate Reality Game (ARG) component, in which one of the modes of user interaction comes in the form of clues and puzzles they must work together to solve. These components are what encourage audiences to work together and treat the storyworld as a real space. ARGs can also stand alone, however, and consist of a loose storyworld that is fleshed out just enough to provide a platform for the release of clues. Most simply, the two forms can be distinguished from each other largely by their goals and emphasis. An ARG will seek to converge upon a single point - a solution to a mystery - whereas a web serial story network will present an ever-expanding universe and a narrative that could feasibly go on indefinitely. Because they are generally more concerned with building a narrative world for the characters and audience to occupy together, web serials are thus driven by plot and performance. ARGs are often deployed in similar ways to web serials - they might consist of web pages, videos, message boards and so on, but they also emphasize from the outset their nature as games. They will have a clear endpoint and a discernable goal. The players who participate in ARGs will collaborate, but their focus will be on solving complicated puzzles rather than on contributing to expanding the fictional narrative universe. Web serials will often incorporate ARG elements in order to enhance the narrative's interactivity, but audiences can watch and enjoy the story without actually "playing" and participating in the ARG elements. Because of these distinctions, I argue that pure ARGs are games, and pure web serials (with no ARG elements) are simply television presented through the web. Web serials that incorporate ARG elements, however, are an-Other option; they conflate social networking and storyworlds in a way that specifically defines them as story networks.

[21] Experiences that bill themselves as ARGs are often viral marketing strategies designed to generate interest surrounding a new video, television show or film. One of the first examples of this type of ARG was conceived as a campaign to promote Steven Spielberg's 2001 film A.I.: Artificial Intelligence. [7] Titled The Beast, the game emphasis was clear from the very start, as the goal was to solve a murder. Though a clear storyworld surrounded the mystery (it was set in the same universe as the film, but with no overlapping characters), and some videos were used to drive the narrative and introduce new puzzles (which was quite a revolutionary technology at the time), the puzzles themselves were the focus of the game, and they all lead to a single conclusion. The participants were a large number of amateur sleuths from around the world, but their goal was always to work together to solve the mystery, rather than to contribute to expanding the fictional narrative universe. [8]

[22] Lonelygirl15 and the serials that followed it drew in large numbers of participants because the shows hit upon the desires driving interactive audiences - desire for knowledge, desire to perform, and a desire for agency. The Internet story network is a successful conflation of all these desires: it requires encyclopedic knowledge of the storyworld (most interactive web serials have their own "wiki" so fans can keep track of the numerous characters, clues and plots), any participant can join the performance by posting their own videos or participating in a chat room, and through their participatory agency the fans can actually affect the course of the plot. In many ways, Lonelygirl15's pinpointing of this triangle of influences is a natural and even obvious progression from earlier experiments with Internet narrative, like usenet groups and multi-user dungeons.

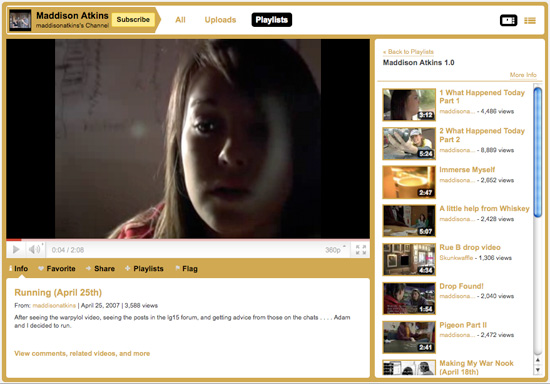

"Collective Intelligence": from Usenet to Wikis

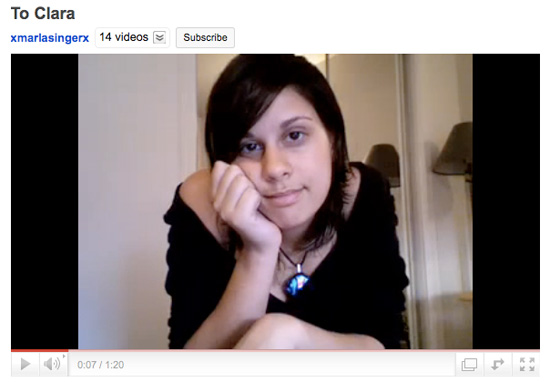

[23] Usenet was one of the first networked communication systems on the Internet, linking together several computer networks that were already in existence. The popular Usenet groups focusing on television shows and films operated similarly to the message boards present on many websites today - they were forums for discussion, theorizing, and informal interaction between fans of the same series or film. The users of these forums were under no illusions that the worlds they discussed were anything other than fictional; instead their fandom was driven by their interest in collecting and categorizing information. This kind of paratextual fascination is mirrored in how fans of television shows like Lost interact today. Lost, for example, had an active network of fans who collaborated through the Internet to decode the show's many mysteries and to participate in its ARG, The Lost Experience. Usenet functioned similarly for fans of Twin Peaks in the early 1990's, as evidenced by the alt.tv.twinpeaks discussion group - it is one of the earliest examples of a television fan culture enabled by digital technology. A fitting precursor to today's ARG-based fictions because of its labyrinthine, interwoven storylines and supernatural interventions, Twin Peaks, like Lost, attracted an avid following because it always suggested mysteries beyond the scope of what a single episode could represent - it suggested, in effect, not just a narrative but a storyworld.

[24] However, though that storyworld prompted a degree of interactivity and immersion, the boundaries between the world of Twin Peaks and the viewer's reality remained distinct. Their interest in solving the mystery was driven by a desire for knowledge rather than sentimental engagement: "The netters pooled their knowledge, shared their mastery, yet held this process at a distance from their emotional lives and personal experiences" (Jenkins: 2006, 126). As such, Henry Jenkins dubs these fans a "knowledge community," deriving the term from Pierre Lévy's conception of the "cosmopedia," which Lévy proposed in 1992 to describe the effect the Internet could have in democratizing information. The numerous strands, allusions, clues, puzzles and unanswered questions provided by this type of show engage the fans' "collective intelligence" (Jenkins, "Interactive Audiences?") and much of their enjoyment comes from processing the surfeit of information as a collective entity by categorizing and speculating through the many shared meeting spaces on the Internet. The process is also analogous to the process of game play, as argued by Steven E. Jones, who notes that, as with a video game, fans are dropped into a complex world and must collect the "tools" and information necessary to understand it (Jones 21-22). These tools are much more quickly gathered with the help of many minds.

[25] As one of the first examples of linked digital networks, Usenet provided a space for a level of knowledge sharing that had not been available to fan cultures in the past. However, this emphasis on knowledge collection and speculation nevertheless betrays a narrativizing impulse as well. In part, this impulse was driven by the fan desire to put a coherent frame around the Twin Peaks narrative. While the show began with an apparently realist (though quirky) aesthetic, it gradually descended into more fantastic and supernatural themes, ensuring that the contextual frame through which the mystery could be solved was perpetually shifting. As Jenkins has noted, how a viewer chose to read even a minor clue had vast implications for their understanding of the entire Twin Peaks storyworld:

Each case made against a possible [murder] suspect represented a different formulation of Twin Peaks' metatext, a different emplotment of its events, that necessarily changed the meaning of the whole and foregrounded some moments at the expense of others...Different theories were grounded in different assumptions about the nature of evil and the trustworthiness of authority...What these competing theories meant was the continued circulation and elaboration of multiple narratives..." (2006,124)

Though the Usenet group members emphasized their interest in the detective work, the implications of that work and how they chose to interpret their clues always implied a choice of contextual frame and thus a particular interpretation of the narrative world. Similarly, the fan speculation surrounding Lost was forced to change drastically when, for example, "others" were found living on the island, or when time travel was introduced as a factor driving the events. For Twin Peaks, however, the very goal of surrounding the Twin Peaks world with a consistent frame can be considered at odds with the project of indeterminacy on which David Lynch has based his career. Laura Palmer's murder is a classic "macguffin," a plot point that purports to be the focus of a narrative but really serves as a cipher around which to explore a grander world and characters. However, the fans' desire for interaction manifested as an encyclopedic mechanism: if only enough information could be compiled, the mystery - and thus the rules, physics and motives - of the storyworld itself could be made clear.

[26] The desire for knowledge amongst television fans of this sort invokes a particular kind of interactivity and enables a mass-interpretive audience that challenges certain conceptions of how narratological meaning is formed. The fans view the storyworld as evolving and complex but simultaneously imagine it as something unitary that can be fully figured out, thus pitting the collaborative processes of knowledge-collection and interpretation against each other. Regardless of the hermeneutic difficulties tapped by this approach, it is important to recognize that the diegetic levels between author and audience remain distinct, and the stakes for that audience remain the same as the stakes for any puzzle-solver or game-player. The Usenet collective and Lost's Internet following have no bearing on the outcome of the story, nor are they bothered by this fact. As Lauren Kogen notes with regard to Lost, we must read interactivity here not "as the ability to affect or mediate the storyline, to have the medium actually respond to the viewer, but to take the story outside the realm of the television set altogether...the viewers are given the chance to feel like they are involved in solving the mystery; the fact that they cannot affect what happens on the island is immaterial" (53).

Along the Identity Continuum: from Text to Video

[27] Television shows that imply fully-fledged storyworlds are bolstered by online interaction, but there is little muddling of subjectivity for the fans who engage in these practices. Looking back again to the early years of the Internet, we can see that identity and performance were issues of interest to users long before graphical interfaces and video capability came into play. Multi-User Dungeons, or MUDs, were driven specifically by users with a desire to perform a variety of identities when they immersed themselves in a virtual world. MUDs were entirely text-based environments in which users interacted by describing (usually fantastic) places, objects and events. As Sherry Turkle elaborated in her 1995 book, Life on the Screen, MUDs were also sites where users could perform a variety of identities. The text-based nature of the games allowed for greater experimentation with regard to how users portrayed themselves, and Turkle cites men and women playing characters of the opposite sex, multiple characters at one time, and characters who fulfilled a wide variety of roles within the fictional universe. She describes the text-based world as a kind of mask through which the users could reveal as much or as little of their real selves as they chose. With the advent of video on the Internet, however, the notions of identity and performance in interactive environments had to change. Many of the viewers who posted their own videos on the Lonelygirl site were less concerned with being someone else and more concerned with being themselves as they interacted with a fictional world. Of course, every video was still a performance, but the visual nature of the storytelling meant that the "mask" behind which they hid was rhetorical rather than literal. In the Lonelygirl universe, this muddling of identity was a site of both opportunity and narrational confusion.

[28] If there is a baseline narrative to the web serial storyworld, it would be in the video "webisodes" published five times a week. Each new video would feature in the center of the website homepage, and previous videos formed a line of thumbnail image links along the left-hand side of the page. Videos submitted by participating audience members were listed in their own set of thumbnails along the right-hand side of the page. Initially this separation functioned well for new users to the site, who could quickly distinguish where the "official" story could be found. However, as audience members began forming their own plots and side-ARGs, and those stories were published in the "comment video" feed, the process of defining text vs. paratext became more difficult. Additionally, the creators soon identified the "comment video" feed as an opportunity to further blur reality and fiction by introducing new characters as commenters.

[29] The first instance of such a technique arrived in the form of "Jonas," a teenage boy who posted a "reply" video to one of Bree's videos in November of 2006, some months after the beginning of the original series. Jonas appears sitting in an office chair in front of a wall of filled bookshelves. His monologue is casual, feels unscripted, and sets him up as just another viewer of the show, carefully obscuring the question of whether he sees Bree's story as "real" or whether he is merely playing along "in game" like many other commentors at the time were doing:

Though he drops a hint that one of his hobbies is video editing, the crisp lighting and use of a few special effects in this video quickly alerted the fans, who immediately began speculating that Jonas was a new cast member. They were right.

[30] Several characters were introduced this way throughout the run of the series, but it also became a site of expansion for fans and other storytellers. Popular spinoff arcs created entirely by fans grew out of the "comment video" feed, the most successful of which was a story that came to be titled Maddison Atkins. This ARG/serial was created by Texas-based filmmaker Jeromy Barber, and thus had no connection to the LG15 creators, but Barber gathered interest and support for his series by setting it in the same universe and introducing the character of Maddison through the Lonelygirl comment videos. Maddison was pretty and quirky, and her videos' production values matched the slick writing and crisp lighting found in the "official" series videos. The fans immediately latched onto her but were surprised when she turned out to be from another series altogether. Regardless, her place on the LG15 page served its purpose, and many fans migrated to her YouTube site to begin following her story.

[31] By far the greatest example of identity becoming muddled through visual performance occurred surrounding a fan named "Marla." Marla was one of the more vocal and well-known participants in the LG15 fan community, posting daily on the message boards and eventually acting as an official moderator. She also became heavily invested in Maddison Atkins. However, she surprised the fan base when, in the summer of 2007, she appeared in a video discussing problems occurring in the Maddison universe with two other well-known commenters, and told them she was going to Texas to speak with the characters. In her next video, she actually appeared alongside characters in the show, and soon became a major feature in the narrative arc. Fans were uncertain about how to respond - how had this real person suddenly become a character? An "LGPedia" (Lonelygirl wiki) entry eventually cleared the matter up: in reality, "Marla" never existed in the first place, but nor was she a character introduced specifically with the intention of weaving her into the show. Her real name was Maya, and she had created a partially fictional persona in "Marla," through which to present herself in her videos. When she later joined the cast officially, that persona became her character in the Maddison Atkins universe.

[32] Marla's story exemplifies the impact of visual culture on the performance of identity. Even though she began as a commenter and moderator on the Lonelygirl site, she was visually recognizable by other participants from her videos, and thus had to remain "Marla" as she migrated to the Maddison Atkins series. Just as the narrative of Internet story networks becomes a cross-platform, transmedial construct, Marla's partially fictional persona, too, became a transplantable entity. She could not, however, suddenly appear in Maddison Atkins with a different personality and name, because her value to that series was her recognizable position as a supposedly "real" person. The text-based environments of the early 1990's enabled a more literal cycling through selves that could be "played" simultaneously, but in the video-mediated worlds of web-based interaction, the self a person performs is much more closely related to the person they are when the camera stops rolling, thus once again emphasizing how reality and fiction become conflated in new and exciting ways.

[33] Narratives like Lonelygirl15 and Maddison Atkins have taken advantage of current technology to provide users with the experience that earlier digital forms like Usenet groups and MUDs could not. The speed and convergence of digital communication are essential to their success, as are the relative accessibility of consumer digital video technology. They are satisfying consumer desires for knowledge, performance and narrative agency, and contributing to an ongoing dialectical process in which these audience desires encourage new technological developments, which in turn produce new audience desires. The tension between these two nodes is what enables a story network to evolve and flourish.

Looking Ahead

[34] According to theorist Michael Heim, a virtual world is defined as a whole - not fragments, not a collection of parts, but a complete world - that is separate from a space we think of as "home." "Home is the node from which we link to other places and other things...Home is the point of action and node of linkage" (Virtual Realism 92). This wholly cognitive division between the real and the virtual is what defines the space of the virtual. In this article, I have tried to undermine this division by describing narratological spaces that occupy the real, the virtual, and a thirdspace. The users who participate in Internet story networks are savvy students of media and storytelling. They spend as much time analyzing and commenting upon storyworlds as they do contributing content to them, and as the stories of Bree and Maddison Atkins demonstrate, the users are invested in these narratives as something more than stories that take place somewhere else, inside a television set, on a computer screen, printed on a page. The world of these stories is their own world, and it is both virtual and real, physical and imagined.

[35] This blending is possible because, as many media theorists have argued, from Baudrillard onward, we are already immersed in the hyperreal. Not only is the simulacrum a reality, it has become the very node that constitutes "home," and thankfully, users have begun to play with it. Media convergence and the blurring between reality and fiction will undoubtedly play a role in future modes of entertainment, but are performative web serials a passing trend or the new standard? A growing number of people are becoming aware of Internet serials and Alternate Reality Games, but by and large they have yet to enter the mainstream. [9] Viral marketing employs many of the same tactics, but it has already become a tired technique to the savvy users who pride themselves on their ability to see through the gimmick. Nevertheless, there is still something fresh and interesting about the possibilities of digital convergence, and it seems to fulfill a desire in audiences to explore fictional worlds and narrativize real life. In a 2009 interview, filmmaker Guillermo del Toro spoke about the changes ahead in similar terms:

In the next 10 years, we're going to see all the forms of entertainment - film, television, video, games, and print - melding into a single-platform "story engine." The Model T of this new platform is the PS3 [Playstation 3]. The moment you connect creative output with a public story engine, a narrative can continue over a period of months or years. It's going to rewrite the rules of fiction (Brown).

ARG-inflected web serials may be a step toward that engine, but their essential quality - and what del Toro leaves out - is their inherent ability to turn the immersive digital reality of the everyday into a partly-fictional construct. Again, the question returns: where does the narrative stop?

[36] This is the question currently troubling narratologists and fueling ongoing debates concerning the specificity or breadth of a suitable definition of narrative. Among other difficulties, a too-narrow definition fails to encompass a variety of media, and when too broad, "narrative" becomes indistinguishable from "life itself." However, the power of story networks is their ability to blur the lines between life and narrative by urging users to see the fictional world within their own reality, thus leading them to narrativize aspects of their personalities and lives. In her discussion of interactivity, Janet Murray states that "the great advantage of participatory environments in creating immersion is their capacity to elicit behavior that endows the imaginary objects with life" (112). In turn, I argue that the great advantage of story networks as participatory environments is their capacity to elicit behavior that endows real, everyday events with narrativity. When one participates cognitively in a story network, daily events become acts of representation, and the experience is thus of both "life" and "narrative."

Works Cited

Barber, Jeromy. Maddison Atkins. 2007. Web. «http://www.maddisonatkins.com/».

Beckett, Miles et al. Lonelygirl15. 2006. Web. «http://www.lg15.com».

Booth, Wayne C. The Rhetoric of Fiction. Second edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983 (1961).

Boyd, Danah M. and Ellison, Nicole B. "Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship." Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1): 2007. «http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/boyd.ellison.html».

Brown, Scott. "Q&A: Hobbit Director Guillermo del Toro on the Future of Film." Wired. May 22, 2009. «http://www.wired.com/entertainment/hollywood/magazine/1706/mf_deltoro?currentPage=2».

Day, Felicia, et al. The Guild. 2007. Web. «http://www.watchtheguild.com/».

Hagedorn, Roger. "Technology and Economic Exploitation: The Serial as a Form of Narrative Presentation." Wide Angle 10.4 (1988): 4 -12.

Hayward, Jennifer. Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997.

Heim, Michael. Virtual Realism. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Herskovitz, Marshall and Zwick, Edward. Quarterlife. 2007. «http://www.quarterlife.com/theshow/view».

Hughes, Linda K. and Michael Lund. The Victorian Serial. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991.

Jenkins, Henry. "'Do you Enjoy Making the Rest of Us Feel Stupid?' alt.tv.twinpeaks, the Trickster Author, and Viewer Mastery." Fans, Bloggers and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: New York University Press, 2006. 115-133.

Jenkins, Henry. "Interactive Audiences? The 'Collective Intelligence' of Media Fans." Web. «http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/collective%20intelligence.html».

Jones, Steven E. The Meaning of Video Games: Gaming and Textual Strategies. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Kogan, Lauren. "Once or Twice Upon a Time: Temporal Simultaneity and the Lost Phenomenon." Film International 4.2 [20]: 2006, 44-55.

Lessig, Lawrence. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. London: Bloomsbury, 2008.

Loiperdinger, Martin. "Lumière's Arrival of the Train: Cinema's Founding Myth." The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists 4.1 (Spring 2004): 89-118.

Mateas, Michael. "A Preliminary Poetics for Interactive Drama and Games." First Person: New Media as Story, Performance and Game. Eds. Noah Wardrip-Fruid and Pat Harrigan. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004. 19-33.

Murray, Janet. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

Nunes, Mark. Cyberspaces of Everyday Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Parfeni, Lucian. "YouTube Streams 2 Billion Videos Daily." Softpedia. Web. May 17, 2010 «http://news.softpedia.com/news/YouTube-Streams-Two-Billion-Videos-Daily-142159.shtml».

Roiphe, Katey. "The Language of Facebook." The New York Times. August 13, 2010. Web. «http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/15/fashion/15Culture.html».

Ryan, Marie-Laure. Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Smith, Barbara Hernstein, "Narrative Versions, Narrative Theories." Critical Inquiry 7.1 (Autumn, 1980): 213-236.

Soja, Edward W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1996.

Turkle, Sherry. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Weisman, Jordan, Lee, Elan and Stewart, Sean. The Beast. 2001. Web. «http://www.cloudmakers.org».

Notes

[1] The narrative of Lonelygirl15 moved through several (sometimes contradictory) plots as it responded to sudden notoriety and expansion, but in brief its focus was on 16-year-old Bree and the mysterious cult of which her family were members. As the cult's presence became more ominous, Bree and her best friend Daniel (along with other characters who were gradually drawn into the story) sought to fight back and unlock the deeper mysteries surrounding its purpose and goals.

[2] Cinematic myth has it that when the Lumière brothers first screened their 50-second film, L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de la Ciotat (Arrival of the Train at La Ciotat Station) in 1895, the audience was frightened of the moving image of a train heading toward them and some even ran, terrified, from the theater. This has been challenged as unfounded in recent years (see Loiperdinger), but the story remains a stubborn piece of bedrock in cinematic history.

[3] Danah M. Boyd and Nicole B. Ellison define social networking websites as "web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system" (2007).

[4] Mark Nunes has proposed a useful model in Cyberspaces of Everyday Life (2006), with his emphasis on cyberspace as "lived space" in our society of network communication. Nunes challenges the conception that the "space" of cyberspace is purely metaphorical, "an artifact of language" (5), and rightly argues that this fails to account for materiality and presence.

[5] Consider, for example, mass-authored "round-robin" or "composite" novels, which became popular as early as the late nineteenth century. These novels occupy another significant branch of my research.

[6] See, for example, Roger Hagedorn, "Technology and Economic Exploitation: The Serial as a Form of Narrative Presentation" in Wide Angle 10.4 (1988), 4 -12 and Jennifer Hayward, Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera, and Hughes and Lund, The Victorian Serial. In The Act of Reading, Wolfgang Iser describes how many readers in the nineteenth century "often found a novel read in installments to be better than the very same novel in book form" and attributes that pleasure to the strategically-placed narrative gaps between installments (191).

[7] The entire experience of The Beast as it played out in 2001 is chronicled at «www.cloudmakers.org».

[8] As Steven E. Jones notes in The Meaning of Video Games, viral marketing ARGs will often piggyback on an existing fanbase and community in order to launch products that fanbase will likely enjoy and latch on to.

[9] A New York Times article featuring a work of serialized fiction unfolding across Facebook and Twitter is perhaps evidence that more attention is being drawn to this sort of activity. ("The Language of Facebook," by Katie Roiphe, 13 August 2010.)