Scenes from a Mall

Sudipto Sanyal

Bowling Green State University

Well, the world is gettin' weary, and it wants to go to bed,

Everybody's dyin', except the ones that are already dead.

The answer we're all seeking is starin' us right in the face

All we gotta do is [mumblemumblemumble].

— Hugh Laurie, "The Protest Song"

Scene 1

[1] Bright sunny day, no hint of rain, too warm for my long black coat. While official estimates put the hordes of people gathered on the National Mall, Washington, District of Columbia, at approximately two hundred thousand, Stephen Colbert insists it's actually six billion.

The Porta-Potty Predicament

[2] Row upon row of porta-potties along the northern length of the Mall obstructs all view of the faraway stage. The more reckless daredevils among the rally attendees have already clambered atop some to see things better.

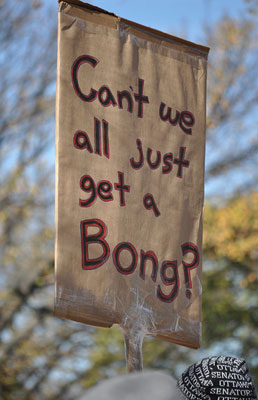

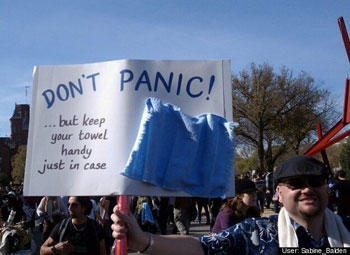

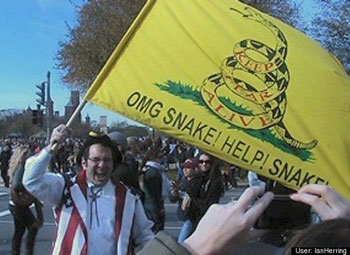

[3] Incidentally, the pre-rally rumours of a porta-potty predicament, i.e., a lack thereof, have been greatly exaggerated; the crisis is averted, thanks, perhaps, to Larry King's generous gift of the first potty for the rally. For some strange, marine-related reason, the Marine Corps refuse to share the 800 or so porta-potties they have organised for the runners in the Marine Corps Marathon, which is to happen the next day. Indeed, marathon organisers promise to padlock their potties beforehand, thereby making the numerous Smithsonian buildings all around the Mall jittery about the state of their loos post-rally. Sometimes, not charging admission fees can come back to haunt you.

Note 1

[4] Thanks, however, to the six billion or so people making their way to the Mall, what would normally have been a half-hour trip by the subway takes us close to two. The line at the metro station extending well beyond the Walmart-sized parking lot outside, and estimated wait times being about the same as the time it might take to just walk to the Mall, we decide to take a cab. This costs us about fifty bucks more, but money no object when sanity is at stake. Also, this is America; no one walks.

Helpful Hint 1

[5] When attending a large gathering (circa 6 billion) – be it to protest partisanship in the media or to drink tea and play croquet – it is always useful to try and arrive at the venue at least a few hours before the event is scheduled to begin, or you might, for a proper view, end up having to scale either the Air and Space Museum facade, or signalposts. Or, of course, porta-potties (see above).

There's something happening here, what it is ain't exactly clear...

[6] The event is, of course, Jon Stewart's Rally to Restore Sanity, in devious cahoots with Stephen Colbert's sister event, the March to Keep Fear Alive – they are, as we find out soon enough, the same thing (not so much a rally or march, really, as a sort of casual milling-about-on-the-grass), thus luring both the sane and the fearful to the same event.

[7] Conceived as a way to satirize the media and its coverage of the political process, the Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear took place on the 30th of October, 2010 – the afternoon before Devil's Night, incidentally – on the hallowed greens of the National Mall in Washington DC, and, as far as rallies go, was remarkably punctual.

[8] To set it in context – Glenn Beck's Restoring Honor rally was held on August 28th, a self-professed "historic" rally that, if he was to be believed, was so earth-shatteringly, monumentally, mind-blowingly, momentously, epochally, astonishingly, sensationally, phenomenally, staggeringly and galactically brilliant that it marked "a turning point in America." Not content, of course, with merely making history, Beck told his listeners on the June 10th broadcast of Premiere Radio Network's The Glenn Beck Program that, because "the government wants to shut [gathering at the Mall] down, because god forbid you have people, you know, gather at the Lincoln Memorial," the 8-28 rally would be making "double-history," which, admittedly, is quite a lot of history to make in one day.Other expressions – only the most skeptical will call them hyperboles – used by Beck to predict the sheer wonderfulness of his rally included calling it "a defibrillator to the heart of America," "the Woodstock of the next generation," "a shockwave," and so on and so on.

[9] It was against this background that the Stewart/Colbert rally was organised, and while Stewart maintained that his rally was never intended to counter Glenn Beck's rally, in timing, effect and consequence, it was nothing if not politically oriented. Indeed, one might argue that Stewart's excuse – "the march is merely a construct... merely a format... to be filled with material that Stephen and I do" – is in itself a confirmation of the thoroughly politically-entrenched nature of the rally in a postmodern world where form itself is often seen ascontent and where the medium may very well be the message.

[10] In all honesty, though, and perhaps because of Stewart's constant disavowals, no one really knew exactly what the rally was about for the longest time. The media was thoroughly confused – CNN's T. J. Holmes called it a "...something...we're trying to figure it out" – and most commentators simply didn't know what to make of it.

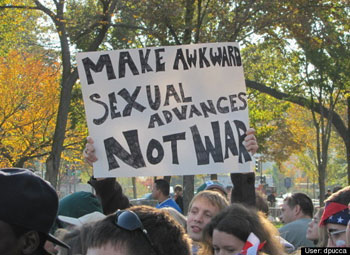

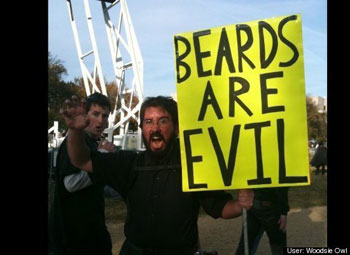

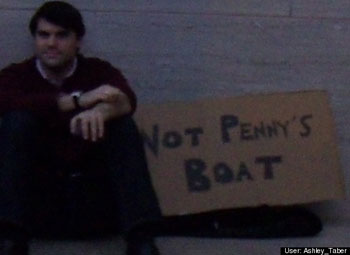

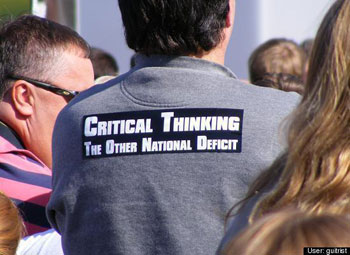

[11] This points to an interesting conundrum about the position of satire in the modern Western world. As Matt Russell shows in "How Irony Killed Satire: An Earnest Investigation," satire now frequently functions as a blank signifier, emptied of its transformative potential. If anything, it now works within a space of absence, where the potential for satire is almost always more powerful than its exercise.

[12] Consequently, the Rally to Restore Sanity incorporates this space of absences to open out a new sort of space, that of the double. At the level of form, the rally is double-formatted – first, as a rally and all that the word implies, and second, as a fairly hermetically enclosed rock concert (acts as diverse as Tony Bennett, Kid Rock, Ozzy Osborne, The Roots, Mavis Staples, etc. performed intermittently throughout the duration of the gathering) interspersed with non-musical 'segments,' such as the handing out of "Medals of Reasonableness" and "Fear," Sam Waterston reading out the greatest poem ever written, Colbert's 'Are You Sure?' ("Did you hear that? No? You're probably going deaf," is how it begins), and other special guests like Kareem Abdul Jabbar and R2D2 (yes, yes, that annoying robot). On another level, that of intent, the rally might be thought of as an absence of signifiers, an empty framework that, because it had no obvious political point, allowed all who attended to fill it with their own expressions; hence the surreal diversity of signs, in support of everything from marijuana legalisation to free hugs. Indeed, right in front of the Capitol even sat a group of people with picnic baskets, quite topless, offering to pose for pictures with you.

[13] In the strictest sense, then, and in a sort of Barthesian twist, the rally isn't really a rally; but it isn't not a rally either. It's a bird...it's a plane...it's, well, not exactly clear.

Interlude, allowing an explanation

[14] Why have I made the long trek from Bowling Green, Ohio, to Washington, DC? The minor detail of my having planned the trip before I knew about the rally notwithstanding, I think I am thrilled with the way Colbert has been pitching his side of things. A Rally to Restore Sanity is quite alright, but there is a fundamental infelicity at the heart of such a premise – it presumes an independently pre-existing structure of 'sanity' and includes itself (i.e. the organisers, the attendees, its supporters, etc.) in it, and it implies that the 'insane' (whom it has designated thus) are aware of their 'insanity' (a contradiction in terms!) – hence the call to saner arms; discussion, debate, cordial arguments over dessert, perhaps.

[15] There is a paradox at play here. While Stewart announced that this was a rally for those who didn't go to rallies, it still had to be in the form of one. And the purported "timeless message" it would spread – "Take it down a notch, for America" – had serious, earnest undertones, no matter how comedically delivered.

[16] But Colbert's announcement of a March to Keep Fear Alive tapped into a long tradition of unsettling satire, from Juvenal, Jonathan Swift and perfectly reasonable proposals for preventing the children of poor people in Ireland from being a burden on their parents or country, to American Psycho's blistering indictment of consumer capitalism and Colbert's own show, The Colbert Report. It made no attempt at conveying a sincere message, instead holding up in bright neon lights a metanarrative of fear as its cause – make of that what you will, come to the party dressed up as you will, rail against what you will, root for whom you will. Stewart's rally implies a moral position confident in sanity, however defined, and an attempt to impel people towards that position (it also, as Bill Maher pointed out, traded in false equivalences, by "pretending the insanity is equally distributed" over Right and Left); Colbert's merely inquires into a subtext present in contemporary popular discourses of nationhood and tries to provoke further discourse about it in a display of free play – the four qualities of the rhetoric of satire that Dustin Griffin identifies in Satire: A Critical Reintroduction.

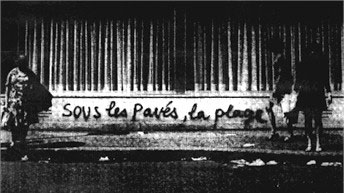

[17] Colbert and Stewart focus their critical lens, then, in the same direction, but Stewart's approach is straightforward, earnest, sane; Colbert's, though, is insane and absurdist, bordering on Dada modes of protest in its deliberate irrationality and its stupendous overblownness. It is here, perhaps, that the problem of the differend that Jean-Francois Lyotard articulates comes into play. For Lyotard, the differend points to an irresolvable conflict "for lack of a rule of judgement applicable to both arguments.... A wrong results from the fact that the rules of the genre of discourse by which one judges are not those of the judged genre or genres of discourse." In other words, Stewart's mode of engaging in conflict with a position different from his is to argue from within his own paradigm (as Thomas Kuhn would term it), not realising that it is a different paradigm from that of those he has a beef with (much like an argument between an atheist and a believer – one argues on the basis of reason, the other on faith; each mode is legitimate within each person's paradigm, but illegitimate within the other's). Hence, the perceived insanity in public life and media is countered by a seemingly healthy dose of sanity, but the opposing phrases – rules of each discursive regime, that is – remain in dispute.

[18] Colbert's method, however, is to enunciate conflict by co-opting the terms of the opposition and blowing them all out of proportion (some might say, taking them to their logical limit-situation), thereby highlighting the inconsistencies and absurdities at the heart of that discursive order. Throughout the rally, Colbert and Stewart keep up a parodic debate between reasonableness and fear, with Colbert usually expressing victory on each point. In the finale, however, Colbert and his giant papier-mâché puppet Fearzilla are made to melt into the stage by Peter Pan, played by Daily Show correspondent John Oliver, who leads the crowd in an anti-fear chant, thus handing Stewart and the forces of reasonableness ultimate victory. In the process, this ensures a veering back to earnest, rational modes of protest/conflict, a denial of the open-endedness of Colbert's Dada form of protest, and a discomfort with ending what was supposed to have been a parodic rally parodically (hence, Stewart's earnest, far-from-satirical concluding speech). Could Tom Lehrer really have been right all those years ago when, in the aftermath of Kissinger being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, he declared satire to be dead?

[19] To get back to the rally then, well, sanity can sometimes be overrated, but Hitler's never going out of fashion.

Collective Fetishistic Disavowal

The most basic coordinates of our awareness will have to change, insofar as, today, we live in a state of collective fetishistic disavowal: we know very well that this [a "rogue nation" obtaining a nuclear weapon and announcing its "irrational" readiness to use it] will happen at some point, but nevertheless cannot bring ourselves to really believe it will.

- Slavoj Žižek, Living in the End Times, x

[20] The mad and virtuosic Slavoj Žižek warns us from approaching capitalism as a psychological problem, i.e., its failures should not be evaluated as private psychoses leading to collapse; rather, it is capitalism's systemic faultlines that need to be examined. In much the same vein, perhaps it is necessary to keep in mind certain disturbances that kept rippling, on and off, through the discursive order of the rally that day. Jon Stewart's concluding speech is impassioned, heartfelt, sincere, and elicits cheers that are in their intensity reminiscent of corks popping violently from champagne bottles; it is also naive in its proclamations of nationalist pride in Americans "work[ing] together to get things done every damned day!" We live now, Stewart argues, "in hard times, not end times."

[21] Žižek would disagree. In his most recent book, Living in the End Times, he attempts a political analysis of our contemporary moment as approaching "an apocalyptic zero-point" – not a point in time when things will finally collapse, but a continuum of rapidly-escalating problems (economics, neo-apartheids, ecological issues, etc.). Žižek's point also is that when we now conceive of change in any form – social justice, more tolerant laws, more equitable economic reform, etc. – we engage with issues within the broader purview of the dominant system. Stewart's concluding remarks similarly remain entrenched within the dominant idea of Americanism and its contentments, pointing out the gloriousness of the common American in the equality between an atheist obstetrician and an Oprah-loving NRA member. His easy separation of the media (that he describes, famously, as a "24-hour political pundit perpetual panic conflictinator") from the larger military-industrial-entertainment complex can only operate on the premise that it is not the system itself which creates the symptom, but that it is merely the symptom that needs to be treated, and life goes on, bra, la la how the life goes on.

[22] Conflict, Jon, is the origin of everything. Heraclitus.

Poetry is in the street

[23] Yet, what is truly wonderful is the heterogeneous assemblage that springs forth onto the Mall this afternoon – there are:

,

,

,

,

Little Lebowski Urban Achievers

,

,

,

,

,

,

Hitler Youth

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

Striking nudists

,

,

,

,

Frankfurt Schoolers

,

,

and even Ohioans

.

.

Manufacturing Dissent

[24] Most of these 6 billion attendees are at least somewhat irritated by the state of public affairs, and they've turned up to show it, in bright colours and irreverent smiles. This is a strange, almost Situationist-inspired happening – a rally about rallies, a protest to protest overamplified protestations – where the attendees are far more politically engaged than the organisers. As Raj Patel noted, "Pining for 'sanity' during the rise of the Tea Party is like talking about who leaves the seat up when the house is on fire," but power to Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert and Comedy Central, not for fomenting dissent among the populace, but for renting out the Mall (or whatever the strict procedure for such things is) and turning it into a tangible public space of laughter in the dark (even if somewhat "impotently polite laughter"). It is wonderful, therefore, to see people clambering up the facades of venerable Smithsonian institutions and chuckling incessantly and for no reason at all. The hodgepodges ("combinations of interpenetrating bodies," as Deleuze defined them) that have come together on the Mall (again, only at the level of the attendees, not the organisers) express a structure of feeling that Deleuze might have been greatly in favour of – recall his idea of society as being defined "not by productive forces and ideology, but by 'hodgepodges' and 'verdicts.'" Yet, this is a weirdly quiescent gathering, strangely Situationist-inspired in the surreal poetry of its component pieces, signs, people, but far from radical when experienced holistically (it happens not as provocation but by invitation, for instance). It infuses some much-needed magic into our ennui-ridden everyday lives, functioning somewhat like a larger, more punctual version of a flash mob rebelling against the tyranny of muzak by performing Bolero at the Eldon Square bus centre in Newcastle, for instance, but beyond that, it achieves very little (indeed, far more pointed is the post-rally conversation between Democracy Now!'s Amy Goodman and environmental advocate Van Jones about the media, the upcoming Midterm elections and community organising, held in a packed-to-the-rafters Busboys and Poets on the corner of 5th and K).

[25] However, there is a caveat here, and it's a big one. Looked at conventionally, the rally does indeed achieve very little in terms of any focused political consideration, but this, I think, points to another contradiction in the increasingly absurd state of affairs in this part of the world. Ever since Obama assumed the position of "the leader of the free world," power and authority have come to be represented, however mistaken and racist the bases for such, in his body – as a minority – and in his perceived 'socialist' tendencies, however loose or inaccurate these perceptions. Consequently and suddenly, dissent, a sentiment that has traditionally been associated with the disenfranchised, has become a right-wing commodity. [1] With the rise of the Tea Party in particular, protest as a political methodology has been systematised into a constellation of knee-jerk and violent abruptions. What we are seeing here is a process in which the very act of protest is being co-opted by an ideology/collective sentiment that has conventionally been the target of such action. This involves, of course, a great sleight of hand, an insidious attack on perception and language that relies on obscuring any total shift to the right by tapping into this rhetoric of dissent (and certainly there has been occurring a movement, both in the U.S. and in Western Europe, a gradual movement of the political spectrum towards the right, a trend on which commentators as different as Bill Maher and Slavoj Žižek seem to agree). Thus, while the rally's somewhat anti-politicization message, if it can be called that – it was, after all, aimed at people who don't usually go to rallies, with its implication that they'd stop again after this one – is perhaps theoretically inexpedient, in practice, at this historical moment, against the larger backdrop of the co-optation and manufacture of dissent, such a message might certainly be thought of as desirable in some cases.

Vox populi, vox dei

[26] In a perceptive article on the whole Wikileaks fracas, Saroj Giri points out how the events transpiring recently with respect to Wikileaks demonstrate that 'the truth' has become an end in itself, without necessarily leading to any sort of sustained political action. Meditating on "the multiplying, faceless, rhizomatic swarm... of the anonymous many" that constitutes any kind of politically active public, Giri observes that "as the present WikiLeaks episode shows, the anonymous many seem to be bugging and embarrassing power, but they are without any vision of real change." The crowd on the Mall is wonderfully playful and good-humoured, but at the end of the day, as the clock strikes three, the show comes to an end, and everybody starts to disperse, and an undeniable feeling of having been to a rather substantial block party where you didn't really do much lingers on in the back of your mind.

[27] And sadly, no instances of arson or serious vandalism.

[28] What this abhorrent lack of violent expression and Stewart's insistence, cheered on wildly by the crowd, on toning down the rhetoric of extremism in both media and government points to is a 'hodgepodge' – consisting of movements, gestures, "interpenetrating bodies" – that tends, in its collective inflection, towards the category of what Roland Barthes called "the Neutral." The rally-as-hodgepodge is ontologically premised upon, "dodging or baffling the paradigmatic, oppositional structure of meaning, [it] aims at the suspension of the conflictual basis of discourse." In its attempt at suspending this "conflictual basis," this Neutral hodgepodge functions, as does Stewart, through disavowal – disavowal of a focused objective, disavowal of a particular side, disavowal of overt protest behaviour, disavowal of permanent solutions (one could perhaps draw a delicate link in the "psychotopology" of the rally with that of Hakim Bey's Temporary Autonomous Zones which, forsaking enduring revolution, embrace more fleeting insurrection, concentrating on "temporary 'power surges,' avoiding all entanglements with 'permanent solutions'"). Thus also the hodgepodge's "indifference toward the act of producing and toward the product," as Deleuze and Guattari explain in Anti-Oedipus. For many, therefore, this has been their first – and possibly last – rally

[29] Welcome to Vox Populi Lite. As Tariq Ali asked a couple of years ago in a devastating article in The Guardian, "Where has all the rage gone?" The Neutral, though, reserves the right to silence: "What is taking the shape," writes Barthes in his notes for his lecture course on the Neutral at the Collège de France, "of a collective, almost political – in any case, threatened by politics – demand, is the right to nature's peacefulness, the right to silere.... The Neutral = postulates a right to be silent – a possibility of keeping silent."

[30] Is this the tacit, perhaps unthought, impetus behind this event, the demand for less amplification, more silere? Or have we finally given up dreams of the beach under the cobblestones for glittery (and well-scheduled) fibre optic dissension?

Notes

[1] I'm grateful to Arundhati Ghosh for teasing this idea out during a late-night chat that involved large quantities of alcohol, as most late night chats are apt to do.