An Interview with The Freedom Painters

John Lennon

University of South Florida

I first came across the paintings of the Freedom Painters through a tweet forwarded by Robin Wyatt, who had interviewed members of the group on the streets of Cairo in the midst of the Arab Spring. (For his essay as well as photographs of the paintings, see «http://www.robinwyatt.org/photography/?s=freedom+painters». Twitter led me to The Freedom Painters' Facebook page at «https://www.facebook.com/FPainters/info» which, in turn, led to emails and phone calls with the administrators of the group. The following two interviews with Noha Ahmed Abd El-Mageid, a spokesperson for the group, were conducted in January 2012.

1st set of questions

JL: Please tell us about the first time you went out and wrote on a wall. How old were you? Why do you think you went out and did it?

NA: The first time we ever drew on a wall was in February, after the 25th January revolution. We were all college students, aged 18 to 24. Our purpose, back then, was painting for a better looking Egypt, as well as delivering messages we wanted people to see through these paintings that were all over the streets. Half of us knew each other from a previous project, so we were all enthusiastic about beginning another one. (Our previous project was on cleanliness issues and the garbage on the streets).

JL: How long have you been writing? Who are your influences? How would you describe your style? How often do you go out to write? Were you writing before you joined Freedom Painters?

NA: Some of us were applied arts students and some of us had taken up painting as a hobby. But drawing on walls was a totally new experience for all of us. We used to go out whenever we had the money to do so, and whenever we found the right spot—and that was about once every two to three weeks.

JL: Please tell us about The Freedom Painters: its history, its members, its actions, its projected future, etc.

NA: Freedom Painters first started work on 26th February, when a bunch of young people decided to start a project that would deliver their points of view to ordinary citizens walking down the streets. It started through people that knew each other, and the idea spread fast through a Facebook "event" page. The first time we went out to paint there were about 20 of us, and later we would have 50 to 60 participants every time. Unfortunately, we, as Freedom Painters' administrators, have stopped our action for the time being due to lack of funding to buy paint, and since the graffiti we did was somehow illegal; we need permission from the landowners before painting on walls on their property. However, we will resume our work the minute we have permission to do so, provided we also have the money.

JL: Please tell us about the graffiti scene in Egypt. Is there a large scene? Are you part of a crew? What access to paint/markers do you have? How connected are you to other writers throughout the world?

NA: Just like our group, the graffiti scene began to appear in Egypt after the revolution. Some drew on their own, and others belonged to crews. We buy paint, spray, and brushes with money received through donations collected from people on the street. They see us working, that way they know where their money is going.

JL: Take us through a regular day of planning and writing/painting. We would like to know the everyday stuff that goes into planning and then writing.

NA: We, the administrators, allow those who know how to draw choose the piece of art they want to portray on the wall. We provide them with the colors needed, and they start drawing. When the outlines of the picture are done, anyone can help with painting, under the supervision of the person who drew it.

JL: What is the reaction to your work? Is it generational? What would happen if you were caught (or what did happen if you were caught)?

NA: The reaction was surprisingly good. People from all ages were enthusiastic about it, encouraging us to keep going, and urging us to spread awareness through the paintings, like "do not litter," "vote," and so on. An up-and-coming singer, along with his band, even recorded a video of his patriotic song in front of one of our pieces which said, "If I wasn't an Egyptian, I would have wanted to be one." And we never got caught in the year that we worked together.

JL: What, in your view, is the point of graffiti? Do you think of it as art? Vandalism? Is it political? Fun? Resistance? All of the above? None of the above?

NA: Graffiti has always been known to deliver messages and threats from and to gangs. It is still being used as a way of delivering messages, but now it delivers a different kind of message. It is also in trend with the Arab Spring, so yeah, we can basically say that the year 2011 was the year that saw the rise of a new graffiti—a revolutionary one.

Follow-up questions

JL: You stated that the administrators of Freedom Painters knew each other and worked on other political/social issues like "cleaning issues, and the garbage on the streets." Could you explain this more fully? Please tell me about this project.

NA: That project was a campaign dedicated to cleaning the streets of the neighborhood we live in. We did another one after that which involved painting the pavements of our neighborhood.

JL: You started as The Freedom Painters on 26th February. Who came up with the name, and why?

NA: One of the administrators suggested the name, and we approved of it because it was a bit related to what we were doing, and it also captured the mood of the time we were working in (after the revolution).

JL: As revolution spread throughout Egypt, a large number of people took to the streets to demand a governmental change. Why did you all feel there was a need for art? What role, in your opinion, does art play in the revolutionary process? As a side note to this question (and answer only if you feel comfortable doing so), did you participate in the demonstrations in Tahrir Square? Could you explain the reasons for doing so? How did that experience affect your artworks, specifically?

NA: [During the revolution] people thought of different ways of expressing their opinions— some by demonstrations, others through court trials, etc. We thought art was the easiest, simplest way of getting to people's hearts. Everyone on the streets would definitely get ninety percent of our paintings. Whether they agreed with it or not, they still understood what we had to say.

And no, none of us were in the Tahrir Square demonstrations.

JL: Is graffiti art? The reason why I ask this question is that in your responses, you seem to repeatedly make the point that you view yourselves as artists and that graffiti was a form that you adopted to get your messages out to the public. So would you consider yourselves artists who use the medium of graffiti to express your views (just like some artists would use, say, metal, to express their art)? I just want to have a clear idea of your relationship with graffiti.

NA: I can't really provide one answer to this question; we had over 30 painters and artists who participated in this and each and every one of them joined us for a different reason. Some wanted to draw out of passion for art; some wanted people to see their drawings; and some wanted to see their own drawings on the streets. Some, on the other hand, wanted to deliver a message to the public, be it by putting their own opinions across to people, or by making people think about an issue through their graffiti.

JL: Could you tell me a little more about yourselves—age, gender, economic situation, religious affiliations, (if you have any)? Could you then relate how these aspects of your identity affect you as an artist? For example, graffiti in the US is seen as a male dominated subculture (although there are NUMEROUSexceptions). Were there any special pressure/expectations for female participants in the Freedom Painters? If you consider yourself religious, how does this relate to the topics that you choose for your art?

NA: The administrators of the group consist of four men and four women, aged 19 – 23, all medium level. Artists from all genders and of all ages were welcomed to join us; there were no added expectations from or pressures on any one.

JL: How much are you aware of graffiti writers throughout the world? Had you followed or been in contact with graffiti writers before the Freedom Painters came into existence?

NA: Not really. We became interested in knowing more after we actually started the project.

JL: Are the Freedom Painters still on hiatus? How do you go about finding funding sources to buy paint? How much have you already collected?

NA: Unfortunately, we have not been doing graffiti for a while now. Our earlier source of funding—donations from people on the streets—is not going to work anymore.

JL: I was really interested in your view on asking permission to do pieces on walls. There are some in the graffiti community who believe that all walls—private or public—belong to anyone who can hit them. In fact, some believe that the harder (and more illegal) the wall the better. Do the Freedom Painters believe in working within the legal system, and therefore see their work not as vandalism but sanctioned art?

NA: It is true that any wall is a public wall, but for us, it is not okay for anyone to just draw anything. And I am not just talking about the subject of the painting—it's more about the colors, the shapes, how good the artist is. After all, we are part of a team, and anything drawn on a wall has the team's name on it, not an individual's. So taking permission is necessary just to make sure the owners of the property know what is going to be portrayed on their wall.

JL: In the past year plus of being part of The Freedom Painters, have you seen a change in responses to graffiti? For example, how does the SCAF see The Freedom Painters (or graffiti in general)?

NA: I'm not sure how the SCAF sees graffiti, but I believe that it is illegal to draw on a public wall without permission. That's another reason we had to stop, and also why we had to check the subject of the drawings, so as not to let anyone draw anything insulting.

JL: You mentioned that most of you are in university. Do you see a connection between The Freedom Painters and your university education?

NA: No, not really. Many of us are in different universities, but the love of drawing—one of the many reasons we formed a group—is what brought us all together at the end.

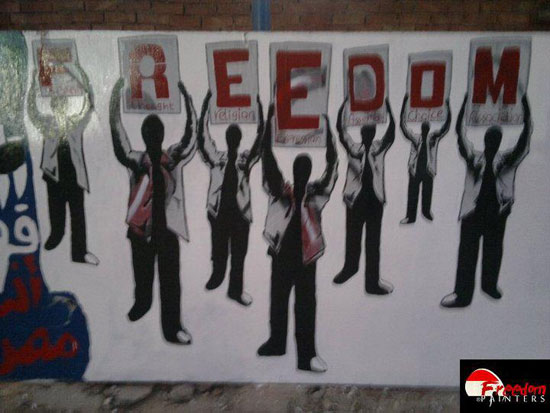

NA: This is in Hassan el Mamoun Street, by Israa Elghazali, one of the administrators. She got the idea from a picture she saw. The picture kind of says it all: people holding letters of the word "freedom."

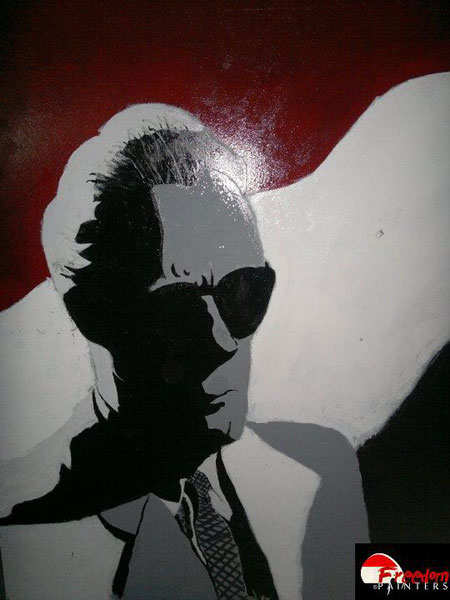

NA: This is a painting of Taha Hussein (Egyptian Nobel prize-winning author, who won the award in1988) by Noran Morsy, another administrator, in Hassan el Mamoun Street. This is pretty much a commemorative piece.

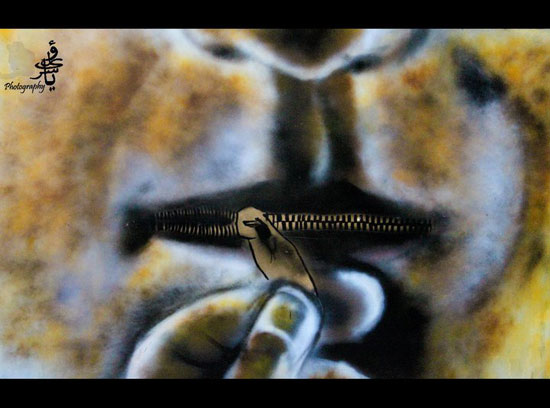

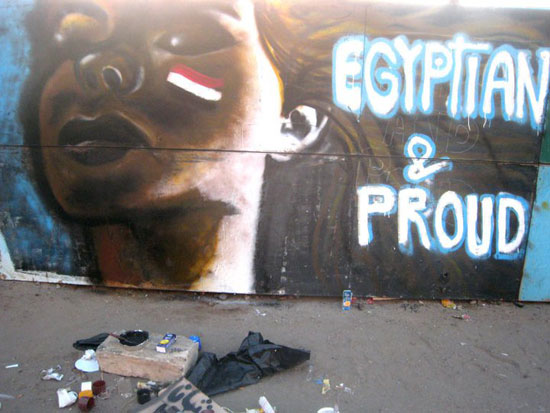

NA: This piece is by Khaled, one of the artists who joined us every time we went painting. He is studying dentistry, and as the picture shows, Egyptian and proud.

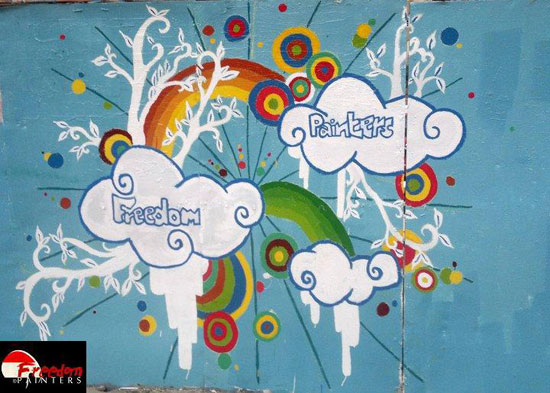

Here are some other photographs of their work that can be found on the streets of Cairo: