Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge

Ecologies of Love and Toxic Ecosystems:

Lessons from the Holocaust in Cavani and Bertolucci

Dr SerenaGaia a.k.a. Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio

PDF

PDF

Abstract

This study analyzes two classics of Italian cinema from an ecosexual perspective. Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970) and Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) share a theme: the 20th century Holocaust in Europe where circumstances are extreme and the ecosystems that host people’s lives are replete with toxicity. The study integrates elements of Deleuzian and film theory, political history, the history of cinema, and cultural discourses about fluid and inclusive practices of love like bisexuality and polyamory. It focuses on the relationship between mise-en-scène, or representation of the physical, emotional, interpersonal, and political ecosystems where characters’ lives unfold, and the styles of sexual and amorous expression they deploy in their intimate scenes. Its approach is unique. It empowers a vision of how the energy of love behaves in toxic ecosystems, surviving as love for love or erotophilia. When the auteurs explore the inner landscapes of the films’ protagonists via Deleuzian time-image sequences, the sexual fluidity and amorous inclusiveness present therein become visible as a way to save love for love in the midst of extreme ecological toxicity. In Bertolucci the fear of love prevails: Marcello kills the woman who inspired love in him. In Cavani this expansive sense of love manifests the imagination of a world where “it is safe to live because it is safe to love.” The author claims that Cavani succeeds because her diegetic structure is organized rhizomatically. The inner landscapes of multiple interconnected consciousnesses are made visible in the interlocked time-image sequences of her dyad Max and Lucia.

1. Overview

This station in the circle is a visit to two ecosexual classics of new-wave auteur cinema where the time-image is used as a research tool about the recent past of Italy and its planetary significance. The Conformist, released in 1970, and The Night Porter, released in 1974, are cinematic renditions of “sheets of the past” from recent Italian and European history that share the wider horizon of the 20th century Holocaust as a theme. Each classic combines the cinematic modes of “movement-image” and “time-image” identified in Deleuze’s philosophy of cinema to tell a story about the energy of love and its behavior in toxic ecosystems. This article offers an analytical observation of how these modalities are organized in the diegetic structure of each film. We will observe how, when threatened with pervasive toxicity, the energy of love can survive as love for love or erotophilia.

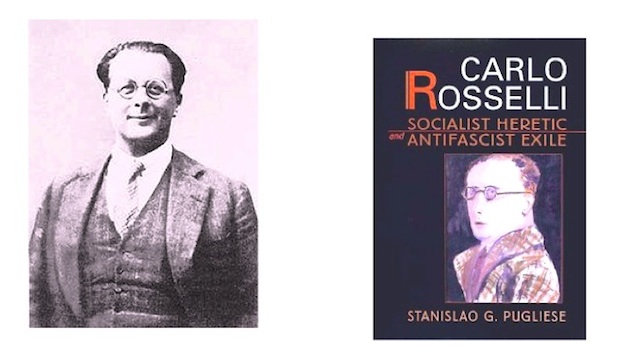

The Conformist is about the killing of Guistizia e Libertà leader Carlo Rosselli, a secular Jew slain as a French exile in 1937. It is based on the interpretation of Alberto Moravia’s novel of 1951 by Bernardo Bertolucci and his filmmaking team. The Night Porter is about internment and interpersonal intimacies between officers and prisoners in a deportation camp during World War II. In The Night Porter, auteur Liliana Cavani is also the main researcher, with her series of intimate interviews with Holocaust survivors informing the work of the filmmaking team.

Both auteurs invent a truth worth believing based on the Deleuzian principle that “the artist is creator of truth, because truth has to be created” (Cinema II, 146). They celebrate amorous inclusiveness and sexual fluidity as practices that make the energy of love more expansive and abundant. Memorable performances by key people in the film’s collaborative teams include Dominique Sanda’s as Anna Quadri, Jean-Louis Trentignant’s as Marcello Clerici, Stefania Sandrelli’s as Giulia Clerici in The Conformist; Dirk Bogarde’s as Max Aldorfer, and Charlotte Rampling’s as Lucia Atherton in The Night Porter.

The experience of a gendered embodiment each director brings to the film and production team is also specific. Bertolucci’s time-image sequences are “arborescent,” or organized around only one character, the anti-hero. Cavani’s time-image sequences are more “rhizomatic” in that they explore the inner landscapes of multiple protagonists. Their intertwined emotions become more visible and resilient. As the stories unfold, different outcomes occur. In Bertolucci’s case, the fear of love prevails and erotophilia disappears. Marcello kills Anna, the woman who inspired love in him. In Cavani’s case, both Max and Lucia are killed, but love for love survives the lovers whose choice represents the wish for “a world where it is safe to love because it is safe to live.” Our claim is that Cavani’s rhizomatic organization of the time-image sequences sutures viewers to an ecosexual perspective on auteur cinema where love for love comes across as more resilient, more capable of overcoming the fear of love that tends to prevail in toxic ecosystems.

As documents of how the arts and humanities, and the art of cinema in particular, function as the sciences that create the belief systems we need, these two films organize the camera’s research work around the Holocaust as a theme that begs questions of transnational significance: What is Fascism? How does it come to inhabit our inner ecosystems? What is captivity, enslavement, torture, abuse? How do these experiences register in the ecosystem of those who suffer them and inflict them? What is love? How does its energy survive in toxic ecosystems? These are the overarching epistemic questions engaged in the two films. They are transnational in nature as well as very specific in their facticity, as becomes the Deleuzian practice of observing both difference and repetition in the rhizomatic formations that constitute the materials for gnoseological research in the art of cinema.

The art of analytical observation we exercise in our visit is guided by our interest in ecosexuality. The ecosexual movement proposes new metaphors for the relationship between sexuality and ecology. Its cultural practices are designed to help the human species reconnect our metabolism to the metabolism of the earth. This partner we all share is us and we are ecosystems. As we envision the earth as a lover, we realize the significance of abusing its ecosystems, including ourselves. As we become aware we cannot claim exclusivity of this necessary partner, we also come to appreciate all those who share her with us. In these terms, ecosexuality operates as an emerging arena of cultural discourse open to aligning sexuality with ecology, and to revealing the amorous visions of love for love that persist, sometimes in a coded form, even in the most toxic ecosystems.

The analytical observation offered by the two auteurs, Cavani and Bertolucci, and their filmmaking teams, conveys lessons that are very simple. When ecosystems are rife with fear, love is impracticable and its energy flees. But love for love stays as a possibility in the inner ecosystems of those whose belief systems are based in erotophilia. If love is the ecology of life, it makes no sense to kill it. Yet the toxicity of the ecosystems that host human life can be extreme, including an extermination camp where Lucia and Max first meet, or a regime where political assassination is the ticket to one’s career, as in Marcello’s case. What can we learn from the self-destructive behaviors of our species? That’s where ecosexual love is useful. When such extreme behaviors are present, we observe the need for a paradigm shift. Ecosexual love can be described as the love that reaches beyond genders, numbers, orientations, races, ages, origins, species, and biological realms, to embrace all of life as a partner with equal rights. As an element of transformation in this shift, ecosexual love reconfigures love as the ecology of life (Anderlini and Hagamen 2015, 13). Erotophilia, or love for love, is the renewable energy that emanates from it.

In The Conformist and The Night Porter situations are extreme. Ecosexual love is the trope that organizes our arts of analytical observation in the discussions presented here.

2. New Waves and Exorcisms

The “new wave” of organizing films around non-linear time was inaugurated in French cinema. It allows the camera to unfold “sheets of the past” of Deleuzian reminiscence, including memories of collective phantasms and fears that need exorcizing through the magic of the screen. In the 1970s, this wave takes hold of many auteurs in the Italian film industry. As we have seen, for Deleuze the brief and intense period and movement of Italian neorealismo marks the shift between classical and modern cinema, with the former based on movement-image, the latter on time-image. Neorealismo is when time-image and movement-image coincide: the motion camera is the instrument in the science of recording history, and experience coincides with the consciousness of viewers. In Deleuze’s view, after neorealismo, the time-image tends to prevail over movement-image, and from today’s perspective we can observe that this is true at least in relation to European cinema. Nonetheless, in the horizon of Deleuze’s theory, time-image and movement-image are modalities related to perspective and technique, production and fruition. There is no objective or epistemic difference between them.

Auteurs of Italian cinema are also known as registi or registe, namely the men and women who hold together the team and project of a film. For them, the call to research non-linear time in the 1970s via cinema manifests as an impulse to revisit the “present” of neorealismo, which is now the recent past of Italy. The camera thus researches the microscopic dimensions of recent history to assess the nature of the “disease” constituted by the ventennio (1922-43) of rule by the Fascist regime. Time-image sequences are used to search for symptoms of this disease in people’s inner ecosystems and to exorcise them for the sake of humankind’s future.

In our two visited films, the respective auteurs propose majestic juxtapositions of movement-image and time-image sequences, each in its ability to connect the mise-en-scène with change, quality, and readability of the energy of love present therein. In both films, we observe how erotophilia manifests as elements of ecosexual love present on the scene, including the potential to love beyond genders and numbers. In the time-image sequences, the camera explores how these elements coexist in the diegesis despite the mise-en-scène and its ecosystemic toxicity. Marcello is the emissary whose inner ecosystem has installed Fascism as its mode of operation. His mind is the object of time-image cinematic exploration for Bertolucci. The officer Max, the prisoner Lucia, and others in the Lager’s unit are the web of people whose interconnected minds Cavani observes analytically in her interlocked time-image sequences.

An ecosexual perspective brings our attention on the difference and repetition of the predicaments the film’s protagonists are in. When it turns out the mission of getting his former professor killed also involves killing the woman who has awakened the energy of love trapped in his toxic inner ecosystem, we understand that Marcello’s predicament is self-defeating. We also understand why both Max and Lucia give up their lives and livelihoods to make sure what they experienced in the extermination camp can be memorialized as love, despite the extreme toxicity of its hosting ecosystem. When love is forbidden, is life really worth living? We can see that Bertolucci’s and Cavani’s cameras organize their analytical observations differently. According to Cavani’s camera, love for love is more resilient. The lovers stay true to their love for love or erotophilia. At the same time we become aware that, no matter what happens to our favorite characters or anti-heroes, we come away with the ecosexual awareness that “a world where it is safe to love is a the only kind of world where it is safe to live.”

3. Amorous Inclusiveness and Sexual Fluidity

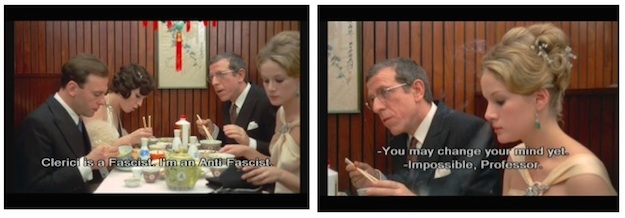

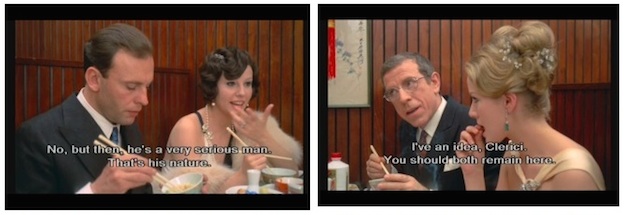

The elements of ecosexual love known as amorous inclusiveness and sexual fluidity organize pivotal scenes in each film and make the emotions of significant characters readable. For example, in Paris we observe Anna love both Marcello and his wife Giulia equally, in an effort to heal the inner toxicity they carry within from Fascist Italy. In Vienna, we observe Max accepting the accustomed affection of Bert, the gay dancer who was also a mate in the Lager unit, even while he is focusing his attention on Lucia. These elements are recognized today as practices of love that characterize polyamorous and bisexual communities and make their sex-positive ecosystems hospitable to expanded networks of emotional sustainability and ecosexual love.

These rhizomatic ecosystems support all participants in practicing the arts of love so as to sustain the kinds of paradigmatic transformations that allow the force of love to stay present in their expanded family networks and communities. The work of these two filmmakers models and anticipates some of these transformative practices. For example, practicing polyamory involves learning to welcome our lovers’ beloveds as metamours. Thanks to the art of amorous inclusiveness, “metamours” are lovers by interposed person rather than rivals. Another practice involves experiencing the emotion of compersion when beloveds receive the love they need, regardless of who the giver is. Thanks to the art of sexual fluidity, we experience the pleasure of our beloveds as our own, rather than experiencing jealousy. In The Conformist, we observe Anna doing exactly this when she welcomes Giulia and Marcello into her Paris home, even while she is aware of Marcello’s connivance with the Fascist secret police. A similar situation occurs in the Night Porter’s Lager, where Lucia begins to experience Max’s tortures as a form of initiatory love and he in turn becomes enamored with her. The camera studies how the energy of love activates their inner ecosystems. This way of studying consciousness through cinema delineates paths to personal and planetary sustainability that uphold the epistemic task Stanley Cavell delineates for this art: cinema is to “save love for the world” even when this cosmic energy is almost extinguished.

4. “Past” and “Present”: Time-Images and Movement-Images

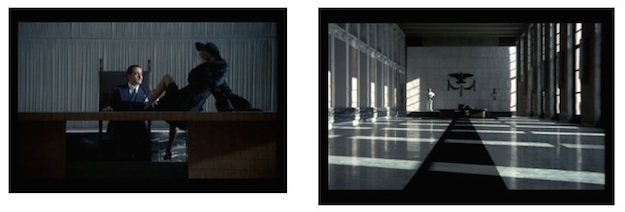

The examples we offer reflect a style of 1970s, new-wave, self-reflexive cinema that addresses planetary questions while it is typical of Italian auteurs in this era. They choose a “present” for the film where they locate the movement-image sequences. For The Conformist, this “present” is Marcello’s 1937 chauffeured trip from Paris to Savoy where the ambush that kills Quadri will occur. For The Night Porter, it’s the 1957 hotel in Vienna where Max and Lucia accidentally meet while ex Nazis are also converging in the Austrian city. This “present” is used as a root directory for the time-image sequences that photograph the inner landscapes of the characters under observation. So, for example, during Marcello’s trip, or when Lucia and Max meet, a certain occurrence is recorded in a movement-image sequence. The sequence photographs the outer landscape: the ecosystem where the movement occurs. The occurrence causes an upheaval in one or more than one character’s inner ecosystems. The camera abandons the movement and jumps into the personal ecosystems to photograph the emotional upheaval that has triggered the processes of memory retrieval. Marcello recalls Anna’s premonitions. Lucia remembers shots while Max was filming. Sheets of the recent past are so unveiled. Planetary questions surface. Why was an entire generation deprived of its most promising leaders? What were the Nazi and Fascist regimes really trying to achieve when they interned people and forced them to labor for free? Why was the energy of love so feared?

Bertolucci and Cavani’s cameras work very similarly. Both rely on “flashbacks” as a cinematic form of “stream of consciousness” technique. Both refer to “storia,” the Italian word that means both story and history and organizes historiography as the narrative science of time and space in relation to human and planetary existence. Both achieve a majestic suture between the two modalities in terms of narrative technique. More to the point, both use what Deleuze calls “time-image” to film “love for love” as the way the force of love persists in the toxic ecosystems. However, in confirming the resilience of love, in studying the power of love for love to transform human and planetary existence, Bertolucci fails where Cavani succeeds. Marcello betrays Anna, the woman who represents love for him. Max and Lucia experience their love fully and come to trust each other completely, even as they are aware that others will kill them. Why? How can the auteur keep her viewers sutured to this sacrificial love? The answer is in Cavani’s use of “time-image.” It’s a “rhizomatic” use in that the minds from which memories are retrieved are multiple, including, most prominently, Lucia and Max, and, to a smaller extent, Bert, the gay dancer who is in love with him. So we are invited to observe exactly how Max and Lucia connect their consciousness as the upheavals occur. Their physical presence to each other evokes fear that transforms into love as their shared memories are retrieved in their inner ecosystems.

It is understandable that when it comes to non-linear cinema, the “sheets of history” that directors from Italy become obsessed with reflect a concern with the country’s recent descent into Fascism: a regime of fear and ignorance where the energy of love fled the region’s ecosystems. The motion camera becomes the research instrument of the science of time and space called history. Art cinema uses it to reinterpret the past and invent a new future. This correlates with the documentary tradition founded by neorealismo of referring to historical events and interweave them with fiction. As in Aristotle, a philosopher often referred to in the country’s educational system, “drama is the microcosm of history.”

However, in these films the camera is not used to exonerate Italians from historical responsibilities, as often happened in neorealismo, where the image of “Italiani brava gente” persisted to confirm the idea that Italians were substantially “good people” deceived into the wrong alliance by a blind leader who landed them on the wrong side of history. As the time-image confirms, this explanation is just not consistent with storia as written in the microcosms of the emotions experienced in people’s personal ecosystems. On the other hand, other “sheets of the past” emerge as memories are retrieved. They reflect ways that time inhabits space in the ecosystems familiar to the people of Italy, including reverberations from pre-Roman antiquity, that reflect ancient belief systems according to which love is an art whose forms of expression are infinite, earth is a sovereign deity and nature is the supreme protagonist of all that is.

The “sheets of history” to which the films we visit refer are very specific.

For The Conformist, the drama is about how valuable cadres are killed. The Jewish expatriate Carlo Rosselli, was, with Piero Gobetti, a founder in the Giustizia e Libertà movement. This movement could have saved Italy from Fascism: in the critical period when Fascists squads took advantage of the new county’s internal tensions and inherent weaknesses, the combination of justice and freedom advocated by the Giustizia e Libertà group could have constituted a sustainable alternative. However, the regime prevented this and consolidated itself by pushing leaders into exile and then getting them killed. Gobetti was done with in 1926, and eleven years later Rosselli’s turn came. A squad of French hit men was hired by Fascist police to eliminate him as a threat to the system. Bertolucci tweaks this based on the “authority” he gets from Moravia’s novel of 1951.

The present time location is the day of the ambush on the road from Paris to Savoy in 1937. Marcello’s memories occupy all the time-image sequences in the film. They begin in Rome in 1917 and continue onwards to the “last supper,” when the former professor and student dine together with their respective wives Anna and Giulia, on the evening before the ambush. A “future” location features what happens to Marcello the day the king of Italy surrenders and the armistice is declared in Rome in 1943. The epistemic question that besieges the movie is: Why does a species become self-destructive?

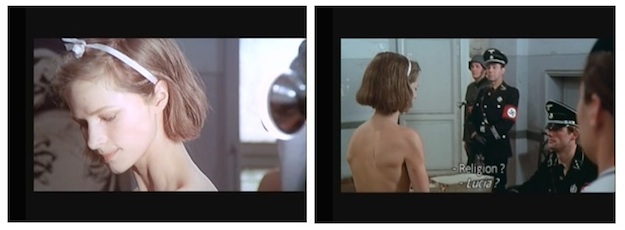

For The Night Porter, the drama is about the teen-age daughter of a socialist who is perhaps Jewish. She arrives at the forced labor camp a virgin, the innocent child of intellectual privilege. In the Lager she becomes an entertainer for the Nazi officers, upon being initiated in BDSM performances by one of them, Max. She understands she has lost her rights and entrusts herself to him. We observe how Bondage, Domination, and Sado-Masochism become part of her existence as she learns to navigate the camp’s toxic ecosystem.

The present time location is the Vienna hotel where Max and Lucia meet again in 1957, as she accompanies her American husband who is a conductor on tour. Two years after the return of Austria to Western Europe (1955), a number of ex-Nazi also converge in that city. In the early 1950s, Cavani’s conducted multiple interviews with Holocaust survivors for RAI, Italy’s public television system, extracting personal memories from women, getting them to speak. That’s her “authority” for making the film. The memory location is an unspecified concentration camp in Nazi Germany and its territories in Northern Europe, could be Dachau, in an unspecified year between the massive deportations of Jews, socialists, gay people, and other dissenters to the forced labor of camps, and the first signals of defeat that resulted in the extermination of prisoners known as the Holocaust or Shoah in Hebrew. The epistemic question that besieges the movie is: What happens to love when situations become extreme?

5. Auteurs’ Sheets of Personal History

The auteurs also have sheets of personal history as registi/e. Both Cavani and Bertolucci are directors with a history of seriously interrogating the boundaries of socially constructed notions of monogamy and monosexuality. In their films, they present concrete cinematic images of “amorous inclusiveness” and “sexual fluidity.” In these sequences, these practices of love anticipate the aspects of ecosexual love participants appreciate in bisexual and polyamorous communities. “Amorous inclusiveness” comes across as the ability to include more than one person in one’s amorous life and emotional landscape. “Sexual fluidity” is the ability to love someone regardless of gender. These abilities are presented in narrative contexts that enhance their potential to get love for love to persist even in extreme circumstances. For example, in all three feature films of her “German Trilogy,” including The Night Porter, Liliana Cavani focuses on what scholar Marjorie Garber has described as “bisexual triangles” where love is sustained by fluidity and inclusiveness (2000). Bernardo Bertolucci is known as a director with a “bisexual” sensibility. Both express these expanded notions of love in erotic terms quite explicitly while they also benefit from mainstream distribution system thanks to the ethos of “auteur cinema.” As a result, a wider public is exposed to their transforming ideas.

6. Ecosexual Diegesis

To better explain how the auteurs involve their collaborators in expressing these themes and suture the public to the artistic intents of the films, we will direct our analytical observation to the diegetic ecology of each feature.

In functional understandings of sexuality, it is often thought that one’s most important sexual organs reside between one’s legs. The groin is after all the area where the reproductive functions are located for primate species. But in an ecosexual context, “sexuality” is just a modern way to describe the arts of love whose forms of expression are infinite. If we allow nature to inspire the arts of love, we observe that sex in nature happens for all kinds of reasons: recreation, fun, social lubrication, pleasure, play, health, friendship, youthfulness. So as an alternative, we offer a special bit of ecosex-positive wisdom. As a sapiosexual would put it, the most important sexual organ sits between ... one’s ears. Sapiosexuals, the cousin erotic species of ecosexuals, are the ones who find intelligence especially alluring. And, as any of them can witness, it’s the mind that turns one on for most people. More specifically, the prefrontal cortex is where the imagination resides, where the fantasies that aliment desire are conceived. That area is known as the third eye in Tantra wisdom, and it’s directly connected to other areas in the chakra system, including the heart, sex, and root chakras.

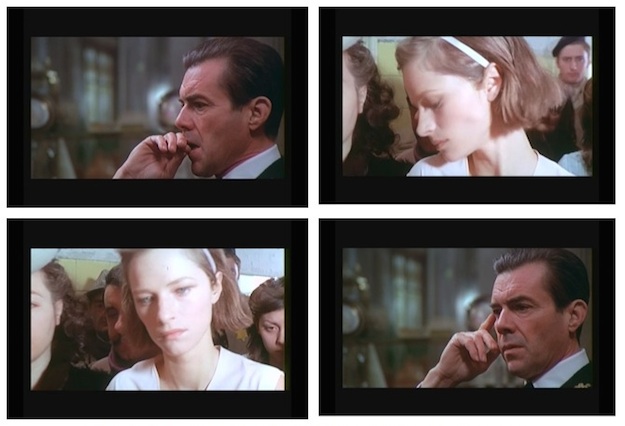

This way of locating the source of erotic energy within a person’s ecosystem explains a lot of what happens on account of the different ways that Bertolucci and Cavani use the time-image sequences. In The Conformist, memories emanate only from Marcello’s mind as he thinks of Anna during the trip. As a result, we observe very clearly that he never comes to know how Anna’s “organ” feels. The Night Porter is very different. As we will see, Max and Lucia’s gazes meet on camera in the initial movement-image sequence. Cavani uses time-image sequences to link that meeting of the gazes to the activation of erotic energies in their inner ecosystems. Memories emanate from their two minds and we know how both of them feel. We see how their “organs” reconnect as they remember their near-death experiences. If you try for size our bit of sapiosexual, ecosex-positive wisdom, you’ll get a sense of why this makes all the difference.

In The Conformist, the train of memory begins when Marcello is molested by Lino. As a kid, Marcello was a bit of a sissy, and his classmates teased him cruelly. Lino, a chauffeur, rescued him and took him to his room. There, Lino stroked Marcello sensually very briefly, upon which Marcello accidentally shot him with a pistol then escaped believing Lino was killed. In The Night Porter, Lucia’s emotions gain traction when she remembers Max dressing her wound right after a torturous session of initiatory shooting.

7. Root Directories: Rhizomatic Uses of Time-Images

This brings us to the claim that sustains our journey. While in both films the camera researches the presence of love for love in the toxic ecosystems, the two auteurs run this search very differently. Bertolucci’s Marcello ends up witnessing the murder of the woman who has inspired this emotion in him: Anna, the professor’s wife whose amorous vision includes Marcello, Giulia, and her own husband Luca Quadri. The fear of love wins. As they reconnect in Vienna, Cavani’s Max and Lucia experience their love more deeply. They become aware that “a world where it is safe to love is the only world where they’d choose to live.” So Cavani’s gaze affirms the force of love for love in a way that Bertolucci fails to do. Why? Our claim is that this is possible cinematographically because Cavani chooses to have multiple “organs” from where the memories emanate.

We might consider sapiosexuality as part of the ecosexual horizon in both films, but for Cavani this mindful proclivity applies to both her female and male lead. When these erotic imaginations come together, the trains of memory meet, the consciousnesses connect, trust begins, and love for love wins over the fear of love.

The root directory of The Conformist is established from the beginning. Marcello rides in the car with Manganiello, the chauffeur accomplice who holds him to the plan mandated by the regime. Manganiello reveals that, contrary to Marcello’s expectations, Anna, the professor’s wife, is in the car with him, and will be killed since the secret police can’t afford any witnesses. Throughout the drive from Paris to Savoy, Marcello’s mind is on Anna. His memories unfold as to why he is in this predicament. That’s how we learn what happened from the day he met Lino, in 1917, to the previous evening. At the ambush site, the diegesis is still “arborescent” in its memory retrieval. No memories from Anna’s mind proceed from time-image sequences in the film. Nonetheless, if we deploy the trope of ecosexual love, we can infer that Anna most likely loves Marcello, because we observe that her love is inclusive. When they arrived from Italy, Anna welcomed both Marcello and Giulia as metamours. While hosting them, Anna even modeled compersion for him when she made Giulia’s honeymoon happier by charmingly seducing her. However, Marcello’s mind is disconnected from others and confused. At the ambush site, he freezes and does nothing for the woman who modeled inclusive love for him.

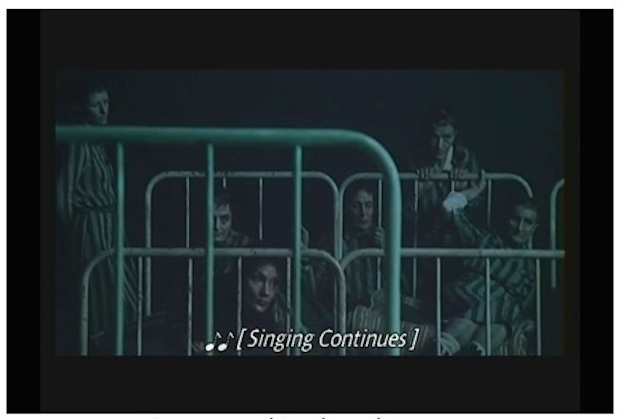

Between Max and Lucia things are

quite different. We observe her as a

naïve teen-ager

when she arrives at the camp. As she

entrusts herself to Max, his initiations make inroads in her ecosystem and she

transforms into an expert dancer who entertains Nazi officers, BDSM style. She gets the knack of Lager life and learns

to navigate the system.

From the initial scene at the reception of the hotel where Max usually works the night shift, we observe how the chemistry of both Max and Lucia’s inner ecosystems changes dramatically as their eyes meet. In this movement-image sequence we observe Lucia in her role as accompanying wife. She is with the American orchestra conductor on his European tour as Max perceives and gradually recognizes her. We see Max perturbed, confused as he addresses the man’s request for keys. Finally, we see Lucia’s inner upheaval in her eyes as they meet his. The energy field between their eyes is dense with intensity, concealed surprise, magnetism, and fear.

This meeting of the gazes is so powerful on screen that it sutures viewers to the film’s journey. At the end of this journey Max and Lucia experience exactly 26 seconds of freedom as they, dressed as the personas by whom their drama was experienced, walk in an amorous gesture along the bridge where Klaus and Bert are about to shoot them.

Here we would like to pause and offer a second take on the claim we propose. We agree that the intent of both films is to retrieve the presence of love for love, or erotophilia, in toxic ecosystems. Time-image sequences are used to excavate under this toxicity until a clean sheet appears. Cavani is more successful in this retrieval and this can be further explained via Deleuzian metaphors too. As we have seen, Bertolucci’s diegesis is “arborescent.” All memories are retrieved from one mind: Marcello’s. As a result, Anna and Marcello’s “organs” are not connected cinematically. Hence, Marcello never understands the inclusive, fluid nature of Anna’s love for him. Cavani’s diegesis is more “rhizomatic.” The two main “organs” are equal in their force of memory retrieval. Memories are also retrieved from the store shared by Max and Bert, and we learn that this gay dancer had a crush on Max since Lager times. We get to observe how Max and Lucia’s memories are similar. When their bodies connect again, the two threads of remembrance meet: they become interwoven. The lovers find again the connectedness that sourced the wish to survive in the Lager. This force is alive between them. They understand the fluid, inclusive nature of their love and choose to re-experience it.

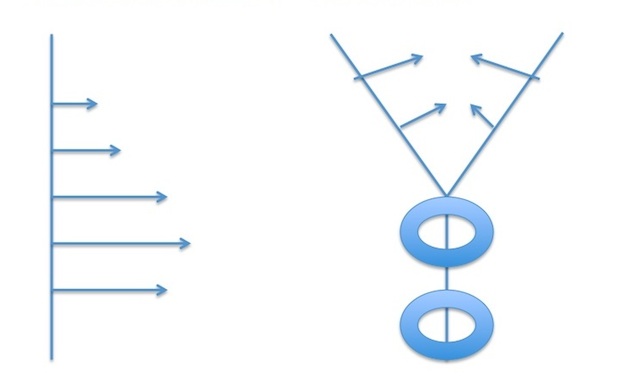

If we were to chart the diegetic structure of the two films, the resulting diagram would look like this:

In the early time-image sequences, we observe Marcello experiencing premonitions about a woman like Anna: one who experiences sexual freedom and is not afraid to be who she is. This happens first when Marcello visits the Fascist Ministry where he gets his assignment to make contact with the exiled professor, and then have him killed. The mise-en-scène deploys the straight lines of Fascist architecture: an ecosystem designed to instill obedience, meekness, fear. But the woman Marcello observes entertain the minister looks voluptuous, seductive, free.

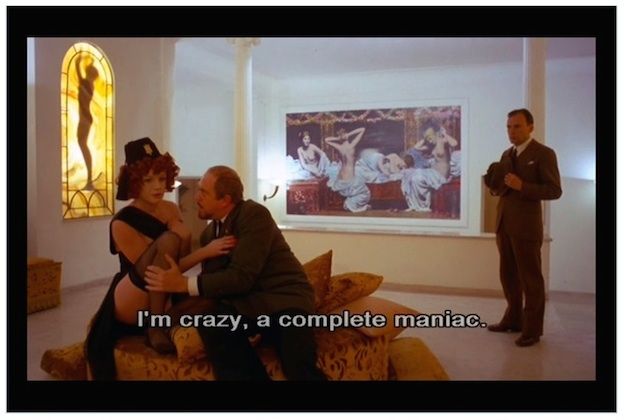

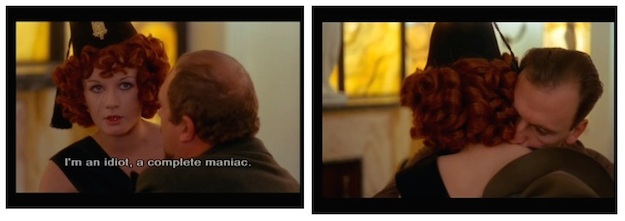

The second figuration of Anna comes when, on his way to Paris to honeymoon with Giulia, Marcello stops at the border city of Ventimiglia. The Anna figure is in a bawdy house and declares herself “pazza” (crazy) repeatedly then wraps him in a warm hug. A figuration of the accomplice who keeps Marcello on task and chauffeurs him is there too.

While Bertolucci focuses on Marcello’s inner emotions as memories surface in the time-image sequences during the car drive, we meet Anna as a figuration: someone who isn’t really the professor’s wife, but looks like her and announces to Marcello a promise of love and freedom.

With Cavani we observe a parallel development of separate time-image sequences that emanate from the meeting of gazes between Max and Lucia at the hotel desk. The energy field created by this eye-to-eye meeting is so powerful that both need a pause from their daily tasks to process the emotions therein. Max sits alone near the opera marquis in a pensive mode that leads into the first time-image sequence. Lucia is in her room when her conductor spouse calls for water. His presence buffers the impact of having Max in her room. To connect with her emotions she retreats into the bathroom. Memories begin to converge as we see the inner film of the same scene shot from two different points of view.

As Max responds to the conductor’s request for room service, we observe how Lucia initially resists the power of memory retrieval the meeting of the gazes has activated within her.

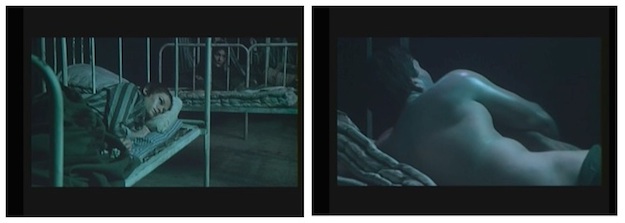

What follows is an extended time-image sequence that expands on Lucia’s experience of entering the camp. Here we experience the confusion of her puberty years, when she remembers a ride on the merry-go-round with gunshots in the background while being filmed. Clearly, things happened very quickly for her. Her protected adolescence was shattered by the deportation which happened very abruptly as they usually did. This is the first time she re-experiences those moments as her emotions are triggered.

There is enough overlap in what the time-image sequences make visible for each witness to be credible to a viewer. We observe the convergence of erotic energy in the field between them begin. At the same time, Lucia and Max’s perspectives remain quite distinct. But the overlap is sufficient to motivate Max to get a seat in the theater pit near the area where the conductor’s wife sits. In their respective trains of time-image memory retrievals, we observe the holographic pattern begin.

That’s where the second meeting of the gazes occurs. The andante con moto movement of Mozart’s The Magic Flute brings out all the power of operatic music to exalt the emotions in the drama of existence. Here we observe the prefrontal cortexes of Max and Lucia activate in synchronicity as the process of retrieval continues with the first sexual scenes.

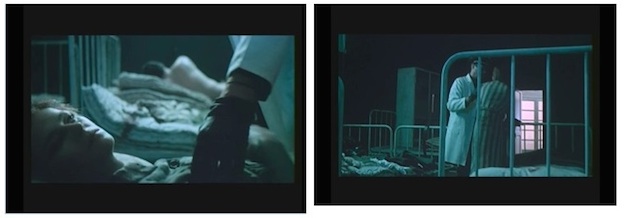

This meeting of the gazes activates the root directories of both inner ecosystems onto a powerful experience of memory retrieval where Lucia’s initiations to sexuality at the camp are in focus. The first time-image sequence photographs the upheaval in Max’s inner landscape and the memories that surge therein. At the Lager, in the common room, an officer is sodomizing a prisoner while others watch, mesmerized by the spectacle of some life therein. The thrusts are perfectly synchronized to the rhythm of Mozart’s climactic scene. Lucia’s affect now is as dejected as other prisoners: victims of modern slavery who have lost their right to self-possession thanks to human abuse. She is mesmerized by the sodomy scene, too, when Max enters the room dressed as a doctor and, in a pretend visit, takes her away from the scene. There is something degrading in the dejection of the prisoners and passive way they watch the scene. We understand that Max feels this is perhaps inappropriate or even dangerous for Lucia. He stages a doctor’s expertise to protect her. While The Magic Flute’s climactic scene continues, we get to move into the inner landscape of Lucia’s personal ecosystem. Max has taken her to a private room and chained her wrists to a bedpost. In uniform he palpates her breasts then inserts two fingers in her mouth. We observe her prisoner affect revived by the attention even though she does not respond to the initiatory abuse.

As we observe the two parallel time-image sequences, we understand what happened to Lucia when Max took her out of the room. We become aware of how he initiated her to oral sex even as he did so without her consent and therefore abusively. We observe how she appreciates the eye contact and personal attention even as she does not respond to the sexual stimulation. We can’t help but consider that the private space and ritual Max has created for Lucia is safer than what might have happened to her in the common room.

The train of memories is powerful enough to get Lucia to stay in Vienna rather than follow her husband to the next station in the tour, Frankfurt. In the next few movement-image sequences we observe how the conductor believes it’s shopping that keeps her. We realize he has a limited awareness of who he is married to. We learn of how Lucia becomes aware of the presence at the hotel of other ex-officers she entertained in the camp unit, including Klaus, Bert, and Hans. At some point Lucia overhears Klaus, the leader of the ex-officers group, exhort Max to help him “file away” all witnesses, or survivors like herself. She calls the switchboard to place a call to Frankfurt presumably to seek help from her husband. And as she waits and relaxes, her next time-image sequence occurs. Here we see that at the camp Max broke the rules just like she did. He came to their dates in civilian clothes. He extended a hand in friendship and she remained indifferent.

We have observed how Cavani’s parallel time-image sequences connect the inner awareness that Max and Lucia experience as their physical persons inhabit the same ecosystem of the hotel where he works, and as the emotional upheavals unfold from the power of eros generated when their gazes meet. This rhizomatic model helps us to understand how their mutual trust and solidarity is built in the movement-image sequences in the film’s “present” in Vienna.

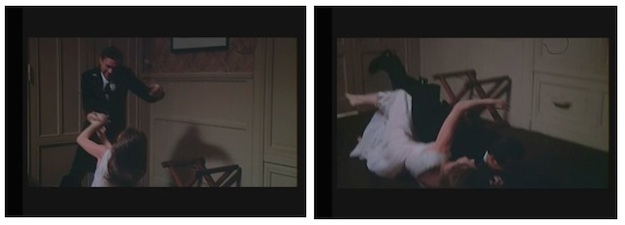

Now we reconnect with Bertolucci’s arborescent time-image sequences as both films approach the time when the two main characters in each film become sexual with each other. We only have access to a sexual scene between Anna and Marcello through his memory. We observe her enter the room of her house in Paris where he is hanging out. Upon which he recalls telling Anna about the pre-figurations that anticipated the significance of her appearance in his life, as the person who could function as a mirror to him, one able to exorcise his fears of love. Anna asks what this woman who looked like her did for a living. Marcello answers: “she was a whore.” Upon which Anna thanks him, her face expanded in a genuine smile, a tad ironic. Then he grabs to kiss her. She resists him and eventually returns his embrace on the bed.

While in this scene we simply observe Marcello’s recollection of having pushed himself over Anna just enough to overcome her resistance, in the corresponding scene of The Night Porter the play of desire and fear is a lot more complex, proving the significance of auteur cinema in using the camera to study the force of erotic love unimpeded by production codes or rating systems. This lovemaking scene is a decisive movement-image sequence that takes place in Vienna in Lucia’s hotel room.

Max reaches his desk to cancel Lucia’s call to Frankfurt then goes up to her room. He wants to know why she is in Vienna at his hotel. He is anxious and smashes a few things. We observe that his erotic energy is activated when he smells her armpits. A race for the door ensues where Lucia tries to escape, even though we know she has stayed for him. By embracing her, he manages to keep her in the room. At that point her erotic energy is activated within and the dynamic changes, as we observe her squat and pull him down until he falls on the floor near her. More emotional and dramatic embraces ensue on the floor itself, until the two finally speak.

Max asks Lucia what to do, and her only reply is “I want you.” As their embrace continues, their non-verbal agreement is to choose each other despite all odds.

Eventually, Lucia moves to Max’s apartment and Max quits his job. On a fishing trip, Max also kills Mario, the only Italian character in the film, who was a cook in the camp unit. Max suspects Mario could give his secret away to Klaus and decides to treat him like an inconvenient witness to be “filed away.” At the funeral, we observe that all the ex-officers are aware of what happened and more than willing to keep the secret.

8. Entrustment: Between Slavery and Freedom

As our parallel between arborescent and rhizomatic time-image sequences continues, we come to the two scenes where Anna and Lucia’s respective feelings are revealed.

Both scenes are presented as time-image sequences. And in both scenes we observe that the two women, Anna and Lucia, are aware of the persistence of slavery in systems that apply human rights selectively and thus produce freedom as the freedom to exploit others rather than to express the energy of love within. Both women are aware that the conflict between freedom to love and freedom to exploit persist within their partner’s inner ecosystems. Therefore, both women entrust themselves to the man before them. Yet while Marcello revisits this scene too late to really act on Anna’s entrustment to him, Max and Lucia, from his apartment where she has now moved, get to revisit her entrustment to him while still a prisoner.

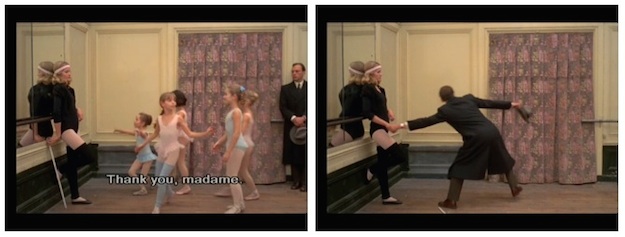

Marcello remembers a visit to Anna’s ballet school. His intent is proposing an escape to Brazil. In which case, he pleads, he would drop everything, including his deal with the Fascist secret police and his honeymoon with Giulia. Anna confronts him with what she knows about him, including that he is a spy working for the Fascist regime. She admits that her husband is aware of this and that’s why he has been received. She voices her disgust for him. At that point, he pleads he’s ready to go back to Rome right away with Giulia. Anna calls him a coward and declares she does not believe him. Then she disrobes and gets sensually close to him. She asks him to hold her. They lock in an embrace similar to the one with the sex worker in Ventimiglia. Anna admits to being afraid. She pleads with him for her husband and herself: “Don’t hurt us.”

In this scene, we can observe what Marcello has trouble understanding. Anna does love him, yet she loves her husband too. To her there is no either/or choice between two rivals. There is a need for inclusion of two metamours. Can Marcello respect her love for the professor he is supposed to kill? If he can, then he can have her love too: her marriage is open and her husband makes no claims to exclusivity. In the time-image sequence, we see Marcello reply to her request that he is not sure. He never imagines that Anna’s love is already his, if only he is willing to share her with others who also appreciate her deeply, and to establish a collaborative alliance with her community while choosing activism for sexual and political freedom as a career.

As the car trip from Paris to Savoy continues, we become more aware of how Marcello feels trapped in his own predicament. Even the chauffeur becomes edgy as he realizes Marcello’s mind is on the woman riding in the professor’s car. We observe how when fear prevails, love flees. Anna entrusted herself to Marcello because she knew neither her husband nor she can stop the secret police. Her hope was to unseat the programming for Fascism from Marcello’s inner operating system.

In The Night Porter we also observe a scene of entrustment. Lucia and Max live together in his apartment. They have chosen each other. And now the hologram of their memories becomes whole. The shopping Lucia did in Vienna guided her toward a pink dress she found in a consignment store. Now we find out what that means to the dyad composed of Max and Lucia. She dons it in front of the mirror while Max is watching. And the time-image that ensues is the first one that emanates from both their minds simultaneously.

In the movement-image sequence, the central dyad in Cavani’s film celebrates the ritual of their commitment as free humans in post-Holocaust Europe, where they believe they have the right to choose each other. This celebration retrieves the memory of their entrustment ritual in the camp, where the toxic ecology of the camp’s ecosystem configured them as master and slave, jailor and prisoner.

9. Compersion

In subsequent corresponding scenes we observe compersion in action in both films. In The Conformist, we observe Anna offer Marcello further proof of her love and acceptance of him by bringing out Giulia’s own sexual fluidity and thus making her more desirable to him. In The Night Porter we observe Lucia’s trick that gets Max and herself to bleed. This brings their awareness of their magical ability to practice love surreptitiously and reciprocally in the midst of the Lager pervasive cruelty. In both cases, the compersive partner experiences the pleasure of the other as his or her own.

Anna wants Marcello to love and respect his own wife Giulia because Anna loves expansively and is aware of how repressed Giulia herself has been in the asphyxiating atmosphere of Fascist Italy. Indeed, we know that Giulia was abused by an uncle and, from Moravia’s novel, we also know that she had a liaison with another woman that she experienced with shame and fear. Anna buys a sensuous dress for Giulia and loosens her up a bit so she can feel charming and enjoy the evening out the four are planning. Anna wants to gift Giulia with the honeymoon in Paris she has been promised by Marcello, in the ville lumière, the city of lights that represents the ecosystem where one’s sexual imagination can expand and be free. Anna is aware that Giulia can use just a tad of seductive attention from herself, and so she caresses her legs just enough to arouse her a bit. The door is open and Marcello is overlooking the scene.

When Giulia responds with a bit of ticklishness Anna drops the tease and proposes to dress her up. Giulia accepts then feels a bit shameful about her nudity. Anna encourages her to be more spontaneous since, Anna claims, she is also a woman. Then Anna turns around per Giulia’s request and looks into Marcello’s eyes through the doorframe. He is now aware that Anna, like him, is attracted to both men and women and can love them equally. Marcello finally sees the fulfillment of his erotic imagination: a woman who can express her love beyond gender to another woman who accepts her sensual tease and does not react with fear. This fear has controlled Marcello since the day he was a kid with Lino, when the man rescued him from his classmates’ cruelty and touched his thighs before giving him the pistol with which Marcello believes to have killed him.

As the drive proceeds, Marcello remembers this scene, and yet his mind is alone as the time-image sequences that emanate from the sexual organ that sits between his ears do not connect to the rhizome of interdependent human existences. He does not know why Anna did this. Was it to prove to him that he did not count? Was it to reveal that she preferred women? Or was it to love him compersively through the love she bestowed on his wife as a metamour? Perhaps Anna was simply trying to arouse Marcello enough to get him to give up his career in Italy and stay in Paris with the expanded family that surrounds the Quadris. We can observe the expansive complexity of Anna’s love if we apply the ecosexual principle of loving beyond genders, numbers, and orientations. However, in the car trip when all this is revisited, Marcello is alone with his doubts and fears.

For Lucia and Max the problem of activating the erotic energy within is quite different. From Max’s initiations, Lucia has learned that camp life is steeped in the kind of Sado-Masochistic cruelty that requires practices of Bondage and Domination that are for real, not for fun as in a container for sexual play where consent is based on a safe-word system. Lucia becomes aware of this when she performs in leathers for the officers in the unit, who all enjoy her seductive allure under Max’s complacent gaze. She sings and the lyrics emblematize her status as prisoner condemned to sadness and whose rights are insignificant. As the words read, if the singer was lucky enough to be happy, she would miss her sadness soon. And sad it is, to be a slave to the Nazi regime, even when one enjoys certain privileges, including the position of princess Salome that BDSM Lucia is inscribed in. Max is totally compersive when Lucia in leathers sits on officers’ laps and poses for them. However, at the end of the dance he surprises her with a cruel gift that reminds her of her abject position. She complained about Johannes, a fellow prisoner who would harass her. At the end of the dance, her reward is a box brought on stage, with Johannes’s severed head inside which is now hers to keep.

The sexuality of Max and Lucia has been wired in this ecosystem of cruelty and extreme toxicity, where life has no value and hearts are bound to bleed, if they have any sensitivity left within them. When Lucia moves to Max’s apartment in Vienna in the movement-image, she is ready to revisit the sensual pleasure she experienced with him in the camp. She is aware that both need to bleed as a Sado-Masochistic way to reenact and consensually access the memories they are seeking. So she locks herself in the bathroom and throws a bottle on the floor. Shards of glass are all over when Max enters with bare feet. She touches his wounds and he pushes down the sole of his foot over her fingers so she gets to bleed too. He raises his hands in surrender to her cruelty. Then the time-image sequence begins that takes them back to the date when he came in civilian clothing and she kissed his chest and nipples sensuously and her response was deliberate as was genuine the pleasure she experienced.

10. Paradigmatic Shifts

The analogy between the two films continues in two subsequent scenes where options are open for paradigmatic shifts. In The Conformist, the south France region of Savoy is where the ambush on Quadri is planned. As Savoy approaches, Marcello’s mind goes to the dinner the night before when Professor Quadri officially made his proposal to him: “Stay with us in Paris. You were one of my favorite students. You will understand a great deal of what’s happening if you chose to do this. It’s an important opportunity for you.” It’s clear from the context that if Marcello considered the proposal, Giulia would not oppose the decision to stay in Paris. Yet Marcello refuses, and, a few minutes later he confirms the appointment with the accomplice who will chauffer him to see that the ambush is successful. It’s the “last supper” for the Quadris. Even though in the dance after dinner Marcello begs Anna to stay in Paris with Giulia, the next morning she chooses instead to accompany her husband to Savoy.

Even though we observe Marcello remember this, we viewers know that he did not accept the proposal because he is on the ride that will ensure that the ambush succeeds.

In The Night Porter, we observe that while living at Max’s apartment, Lucia and Max are besieged. In the movement-image sequences, we observe that the ex-officers of their camp unit have converged in Vienna to meet periodically and clear their consciousness of past responsibilities. They notice Max’s absence and want him to help them “file away” the “dangerous witness” Lucia. He refuses and in retaliation they cut their provisions and sever the power cables too. Bert feels abandoned by Max and Klaus befriends him as an ally in stalking the dyad. Lucia’s husband has telegraphed several times since her move to find out where she is. Hans visits Lucia in an attempt to persuade her to let go of Max. Max quits his job to be near her full time. Life together for Max and Lucia becomes a repeat of the imprisonment experienced in the Lager.

Lucia could end this imprisonment by giving him up and calling the police on him as an ex-Nazi who still does things typical of the Holocaust era, including killing friends on a fishing trip, and kidnapping and imprisoning women. Max reminds her that she is free to do so at his expense if she so wishes. Here is another proposal that involves a paradigmatic shift. Lucia chooses to stay the course of her decision and thus affirms her freedom to express love in the way that feels most authentic to her.

In two subsequent movement-image scenes the reverse analogy is repeated. Along the course of the drive, Marcello’s accomplice and chauffeur Manganiello has become more sensitive to Marcello’s predicament. Manganiello realizes what a senseless fix Marcello is in. And he can feel how this applies in a general way to all those like them. As the ambush site approaches, Manganiello becomes more squeamish about the idea of having to kill a woman. And he senses Marcello can’t take his mind away from her. So to cheer up Marcello he comes up with the cliché that “love can perform miracles.” “L’amore fa miracoli” he exclaims, indicating the possibility that not all bets may be off for Anna and Marcello.

As the ex-officers take turns in stalking Max’s apartment, Klaus finds a way to engineer the murder as he establishes an alliance with Bert. In both time-image and movement-images sequences, we have observed a sensual affection between Bert and Max. As a bisexual man who is attractive to and attracted by both men and women, Max welcomes Bert’s affection even though he does not reciprocate its exclusivity. This mono-poly relationship between a bisexual and a gay man is continuing as the two live in Vienna in the 1950s, and hang out in and around the Hotel Weber and its calendar of events. When Lucia comes back on the scene, Max has less time for Bert and Bert does not offer the compersion Max needs to focus on what’s now most significant to him. So a rift opens between the two, where Bert feels abandoned by Max and seeks revenge rather than giving his friend the space he needs. That’s how Klaus recruits the accomplice he needs to perform Lucia and Max’s murder.

The analogy continues in the final scene of each film. At the ambush site Anna realizes how many thugs have been summoned to make sure her husband is stabbed to death. She does see Marcello’s car in the distance and rushes to it. But the memories from only one root directory have not established the force of love in the energy field between them. Marcello is alone behind the car window even as the woman he loves begs for help from him. The arborescent use of the time-image isolates his consciousness and does not defeat fear.

In the last movement-image sequence of The Night Porter, Max and Lucia have been starved out of the apartment. They attempt an escape by car. While Max drives he sees Bert’s face in the rear mirror. Bert is in the passenger seat of the car that’s following his, with Klaus at the wheel. Lucia is in Max’s passenger seat. Max could make a stop, drop Lucia on the sidewalk, and proceed to safety. After all, that would appease both Bert and Klaus. Bert would get back the lover he thinks he lost to Lucia. Klaus would get to “file away” this dangerous witness. But Max doesn’t do this. Why? Because Max and Lucia’s emotions are connected by the multiple directories of the time-image sequences that sustain the energy of their support system. Max has not followed the procedure for cleaning one’s consciousness in which the other ex-officers in the unit believe. Yet here we see that he has healed. The rhizome has been good for him. Sadly, we see that the minute the two lovers stop their car to take a walk on the bridge, their freedom to love is measured in seconds, as the shots that separate their bodies and kill them reach them exactly 26 seconds after their walk begins. The killers succeed in terminating the life of this dyad, while the affirmation of the force of love in the energy field between them persists. Their death as a two-in-one figure speaks of the virus of love for love or erotophilia that, as a code, entered their personal ecosystems in the extremely toxic camp life they experienced as a master/slave duo. Eventually this code became the link between them that was activated when their gazes met again at the hotel in Vienna. This time they hoped to be free to love each other more fully, and found out that slavery and abjection were still well embedded in the social environments of post-Holocaust Europe.

11. Sharing Authority and Erotophilia

As we conclude our visit to these two majestic studies of human behavior in the throes of toxic ecosystems, we may want to offer some consideration about the nature of erotophilia in cinema.

Erotophilia may be described as the practice of cinema that studies the presence of love for love in devitalized ecosystems, including humans. It is important to keep in mind that the possibility of this practice is related to artistic freedom in the production system.

The European practice of auteur cinema, or cinema d’autore, is one way of protecting this freedom. The success of strategies that employ this system depends on an auteur’s willingness to share “authority”: allow the force of love itself to connect “sheets of the past,” including energy fields between characters, shared memories, and past existences.

Cavani brings to the role of auteur her experience as a woman, with an enhanced awareness of interdependence, symbiosis, and sustainability. Her direction brings together the inner awareness that Lucia and Max share, and offers a view of how love for love can persist in the most extreme circumstances.

These considerations also open an epistemic horizon for cinema. Based on the research offered by Bertolucci and Cavani’s cameras, cinema can certainly be considered the 20th Century art that “saves love for the world.” The arts can be “sciences” that study belief systems and the realities they produce. In cinema, time does inhabit space according to the science of time and space called history. An ecosystem is a system made of interdependent elements whose symbiosis has the potential to sustain life. An ecosexual “truth” worth creating is: “Love is the ecology of life.” Ecosexual Love is the love that reaches beyond genders, numbers, orientations, as well as ages, races, origins, species, and biological realms, to embrace all of life as a partner with important and enduring rights. The practices of sexual fluidity and amorous inclusiveness can resuscitate humankind from its most self-destructive spiels. We must love the Earth we make love on if we want the energy of love to stay with us.

Devitalized ecosystems do not support healthy practices of love. Love survives as love for love, or erotophilia: a virus, or code for an organism, that saves love’s DNA for a better day.

The container of this code is a practitioner of ecosexual love. In Porter’s Vienna scenes, this practitioner is Max, who initiates Lucia, has “imagination,” takes risks, and loves inclusively. Lucia performs ecosexual love in the camp’s BDSM entertainment scene. In The Conformist this practitioner is Anna, who initiates Marcello and Giulia, loves compersively, and welcomes enemies as metamours.

Finally, as our knowledge of love expands via cinema, we may come to an awareness that resonates with the wisdom of love. Does erotophilia in cinema help design a cure for a species that becomes self-destructive? Does it exorcize “Fascism” in all its manifestations, as per Cavani and Bertolucci’s wish? Does it manufacture the love necessary to clear ecosystems of their toxicity? From the auteur cinema of Cavani and Bertolucci we can learn that, in the absence of a space where love can be practiced freely, the presence of love for love is visible in the awareness of those who are willing to overcome fear.

12. Conclusion

In Cavani’s and in Bertolucci’s hands, the art of cinema becomes the science that helps humans invent the belief systems we need. Its teamwork practice is also the humanistic science that studies the belief systems humans have with cinematic precision.

Indeed, The Conformist studies the tension between Anna and Marcello to find proof that the difference between Fascism and a politics of love in which everyone wins is in how we respond to the impulses that guide our personal ecosexual systems. Bertolucci’s camera studies Anna’s awareness of her sexual fluidity and amorous inclusiveness. She owns these impulses and channels their energy into a life of expanded ecosexual love. Marcello remains trapped by his own fears. His inability to love turns him into a murderer.

The Night Porter studies the reunion of Max and Lucia and the way these two survivors choose to memorialize their past relationship as love. The camera observes how they pledge their lives to their shared belief in the presence of love for love within, even when surrounded by the concentration camp exterminating machine. Their pledge is proof that love for love is the only way to bring the flow of this vital energy back into one’s ecosystem, even when it’s almost extinguished. Surviving the extermination of one’s fellow humans is per se a challenge to one’s ability to feel. When they embrace this challenge, Lucia and Max invent the belief system they need. Their rhizomatic bond is resilient as they chose an elegant exit together and thus code the film as a diegetic space where love for love wins.

Works Cited and Consulted

Anapol, Deborah. Polyamory in the 21st Century. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2010.

Anapol, Deborah. Polyamory: The New Love without Limits. San Rafael, CA.: IntiNet Resource Center, 1997.

Anderlini-D’Onofrio, Serena. “I Don’t Know What You Mean by ‘Italian Feminist Thought.’ Is Anything Like that Possible?” In Giovanna Miceli Jeffries ed. Feminine Feminists: Cultural Practices in Italy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. (209-232.)

—. Gaia and the New Politics of Love: Notes for a Poly Planet. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2009.

—. “Polyamory,” in Jo Eadie (Ed.) Sexuality: The Essential Glossary (164–165). London: Arnold, 2004.

— ed. BiTopia: Selected Proceedings from BiReCon 2010. Routledge, 2011.

Anderlini-D’Onofrio, SerenaGaia and Lindsay Hagamen, eds. Ecosexuality: When Nature Inspires the Arts of Love. Puerto Rico: 3WayKiss, 2015.

Beer, Siegfried. “The Soviet Occupation of Austria, 1945-55.” Eurozine. Retrieved September 3, 2016. http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2007-05-24-beer-en.html.

Block, Susan M. The Bonobo Way: The Evolution of Peace through Pleasure. Los Angeles: Gardeners and Daughter, 2015.

Brinkema, Eugenie. “Pleasure in/and Perversity: Plaisagir in Liliana Cavani’s Il Portiere di notte. Dalhousie Review: 84: 3 (2004): 419-439.

Cavani, Liliana. The Berlin Affair. Rome, Italy: Italian International Film, 1985.

—. The Night Porter. Rome, Italy: Ital-Noleggio, 1974

—. Beyond Good and Evil. Rome, Italy: Clesi, 1978

“Chakras.” Wikipedia. Retrieved September 3, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chakra.

Cottino-Jones, Marga. “’What Kind of Memory?’: Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter.” Contention 5: 1 (1995): 105-111.

Cunning Minx. Eight Things I wish I’d Known about Polyamory: Before I Tried It and Fakked Up. CreateSpace, 2014.

De Santis, Giuseppe. Italiani Brava Gente. (Attack and Retreat.) Rome, Italy: Galatea Films, 1964.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema I: The Movement Image (1983). Hugh Tomlinson tr. University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

—. Cinema II: The Time-Image (1985). Hugh Tomlinson tr. University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Tr Brian Massumi. University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

—. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. New York: Penguin, 2009.

Diamond, Lisa. Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2008.

Dietrich, Marlene. “Wenn Ich Mir Was Wünschen Dürfe.” Retrieved Sept 3, 2016. http://lyricstranslate.com/en/wenn-ich-mir-was-w%C3%BCnschen-d%C3%BCrfte-if-i-could-wish-something.html

Marrone, Gaetana. “The New Italian Cinema.” In Elizabeth Ezra ed. European Cinema: 233-249. Oxford University Press, 2004

Garber, Marjorie. Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Giustizia e Libertà. Wikipedia, Entries in French and English. Retrieved August 27, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giustizia_e_Libert%C3%A0; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giustizia_e_Libert%C3%A0.

Johnson, Jeff. “The Counterfeit Self: Ontological Doubt and Narrative Structure in Bertolucci’s The Conformist. NEMLA Italian Studies: 27-18 (2003): 61-73.

Kidney, Peggy. “Bertolucci’s Adaptation of The Conformist: A Study of the Functions of the Flashbacks in the Narrative Structure of the Film.” Film and Literature (1986): 97-106.

Klein, Fritz. The Bisexual Option. American Institute of Bisexuality, 1993.

Kline, Jefferson. Bertolucci’s Dream Room: A Psychoanalytic Study of Cinema. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1981.

Kolker, Robert. Bernardo Bertolucci. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Marcus, Millicent. “Preface.” Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism: XIII-XIX. Princeton University Press, 1987.

Marrone-Puglia, Gaetana. The Gaze and the Labyrinth: The Cinema of Liliana Cavani. Princeton University Press, 2000.

—. “Il portiere di note / The Night Porter.” The Cinema of Italy. Bertellini, Giorgio ed. London: Wallflower, 2004.

Moravia, Alberto. The Conformist. London: Steerforth, 1999. (Originally published as Il conformista in 1951.)

Micheletti-Tonetti, Claretta. Bernardo Bertolucci: The Cinema of Ambiguity. New York: Twayne, 1995.

Milan Women’s Bookstore. Sexual Difference: A Theory of Social-Symbolic Practice. Indiana University Press, 1990.

Loshitzky, Yosefa. The Radical Faces of Godard and Bertolucci. Wayne State University Press, 1995.

O’Healy, Aine. “Desire and Disavowal in Liliana Cavani’s ‘German Trilogy’.” Queer Italia: Same-Sex Desire in Italian Literature and Film. Gary Cestaro ed. New York: Palgrave, 2004.

O’Leary and O’Rawe and Catherine O’Rawe. “Against Realism: On a ‘Certain Tendency’ in Italian Film Criticism.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies: 16 (2011): 1: 107-128.

Orr, Christopher. “Ideology and Narrative Structure in Bertolucci’s The Conformist.” Film Criticism: 4: 3 (Spring 1980): 41-48.

Pietropaolo, Laura. “Sexuality as Exorcism in Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter.” Women in Italian Culture. Ada Testaferri ed. Ottawa: Dovehouse, 1989.

Pugliese, Stanislao. Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Anti-Fascist Exile. Harvard University Press, 1999.

Ryan, Christopher and Cacilda Jetha. Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality. New York: Harper, 2010.

Sapiosexual. Urban Dictionary. Retrieved on September 3, 2016. http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=sapiosexual.

Schermer, Victor. “Sexuality, Power and Love in Cavani’s The Night Porter.” Psychoanalytic Review: 94: 6 (2007): 927-941.

Siegel, Carol. Male Masochism: Modern Revisions of the Story of Love. Indiana University Press, 1995. (Discussion of The Night Porter: 81-87.)

Silverman, Kaja. The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Trahan, Heather. “Relationship Literacy and Polyamory: A Queer Approach.” Electronic Thesis or Dissertation. Bowling Green State University, 2014. OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. 16 Jun 2016.

—. The Rhetoric and Composition of Polyamory. Retrieved January 7, 2016. https://rhetcomppolydiss.wordpress.com/about/.

Veaux, Franklin and Eve Rickert. More than Two: A Practical Guide to Ethical Polyamory. Thorntree Press, 2014.

Waller, Marguerite. “Signifying the Holocaust: Liliana Cavani’s Portiere di notte.” Italian Women Writers from the Renaissance to the Present: Revising the Canon. Maria Marotti ed. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996.

Notes

- For this study I am indebted to all the students who’ve taken my course in Italian cinema at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, to the community of fellows at the University of Connecticut Humanities Institute (2012-13), and to all the leaders and avatars of the Ecosexual Movement who cherished and included me in their events and projects.

- The expressions “sheets of the past,” “movement-image,” and “time-image” come from Gilles Deleuze’s two treatises on cinema (1986 and 1989, passim). “Sheets of the past” refers to the camera’s ability to photograph layers of history in the mise-en-scène that surrounds a film’s action or diegesis (Cinema II, 98-125). “Movement-image” refers to the cinematic modalities where the camera organizes cinematic time around the emotions of the external movement (1986). For example, a cowboy chases an “Indian,” and viewers’ emotions become organized around this chase. In the mode of “time-image” the reverse occurs: movement follows time, and the inner time of consciousness comes into view (1989). For example, a significant person from somebody’s past appears, and the camera jumps to the traumatic memories that this appearance produces.

- About Carlo Rosselli as a historical figure, see Pugliese (1999). About the novel that inspired the film, see Moravia (1951).

- About Cavani’s interviews for the RAI’s Holocaust documentary series, see Pietropaolo (1989) and Cottino-Jones (1995).

- Amorous inclusiveness and sexual fluidity are elements of ecosexual love, the love that recognizes the Earth as the partner we all share. They are often used in scholarship as stand-ins for bisexuality, the potential and ability to love and be sexual with people regardless of their gender, and polyamory, the potential and ability to run multiple amorous relationships openly, simultaneously, and consensually. For more on these I refer to Anapol 1997 and 2010; Anderlini-D’Onofrio 2004, 2009, 2012; Cunning Minx 2014; Diamond 2008; Klein (1993); Ryan 2010; Trahan 2016; Veaux and Rickert 2014. These elements are a very strong presence in the oeuvre of both Bertolucci and Cavani.

- “Rhizomatic” and “arborescent” are two elements in the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari. The first represents horizontality, difference and repetition, and resilience. The second represent verticality, sameness, and vulnerability. Both elements use metaphors from the plant world, where trees and rhizomes coexist (Deleuze and Guattari 1987).

- I refer to the often quoted tagline from my own book, Gaia and the New Politics of Love (2009).

- For more about the cultural practice of ecosexuality and the ecosexual movement, I refer to the multivoiced collection Ecosexuality (2015), Anderlini and Hagamen eds.

- Deleuze discusses the movement-image in Cinema I (56-70). The time-image comes up at the end of Cinema I, where he addresses the relationship of French new wave and Italian neorealismo in Cinema 1 (205-210), and at the opening of Cinema II (1-24). For more on the relationship of French nouvelle vague, or new wave cinema and its reverberations in Italian and European cinema, I also refer to Marrone, in Ezra ed 2004 (233-249).

- For more on neorealismo as a cultural matrix of Italian cinema in subsequent decades, I refer to Marcus (1987).

- The majestic use of flashbacks in The Conformist has been widely studied and has inspired many filmmakers, including Cavani. It has been diagrammed in Kidney (1986). The majestic orchestration of flashbacks, movement-image sequences, and operatic effects within Cavani’s film has been aptly analyzed by Pietropaolo (1989).

- Same reference as in endnote 6.

- The intersections of amorous inclusiveness (aka polyamory) and sexual fluidity (aka bisexuality) as elements of ecosexual love are addressed in a number of interrelated sources, including Anapol (1997, 2010), Anderlini (2009), Anderlini and Hagamen (2015), Block (2015), Diamond (2008), Ryan and Jetha (2010), and Trahan (2016).

- The neologism “metamour” is used in open-relationship communities to refer to the other partners of one’s lover(s). As an important element in today’s polyamorous lexicon, “metamour” denotes the sense of friendliness among participants in open-relationship systems that is typical of these amorous inclusive communities (Cunning Minx 2014; Veaux and Rickert 2014, passim). Polyamory is “a state of being, an awareness, and/or a lifestyle that involves mutually acknowledged, simultaneous relationships of a romantic and/or sexual nature between more than two persons” (Anderlini-D’Onofrio, in Eadie 2004, 164-65).

- The practice of compersion is discussed at length in a number of seminal texts that polyamorous cultures refer to. Deborah Anapol, an avatar of polyamory, describes compersion as a spiritual and embodied practice in her two books (1997, 64; 2010, 121-22). As she explains: “Compersion means to feel joy and delight when one’s beloved loves or is being loved by another” (2010, 121). My discussion of compersion resonates with this: “Rather than denying one’s programming for ... jealousy ... [v]ia a number of spiritual and body practices, one learns to transform this self-destructive energy into ‘compersion,’ the ability to derive pleasure from the love our partners receive and enjoy independently of us” (Anderlini-D’Onofrio 2009, 156). A shorthand for compersion is “the opposite of jealousy.” For more on metamours, I refer to Cunning Minx (2014), Trahan (2016), on compersion to Anapol (1997), and Anderlini (2009).

- In philosophy “rhizomatic” is a descriptor used refer to a formation that expands horizontally by a mixture of variance and aggregation. See also endnote 5.

- The documentary character of neorealismo is addressed in Marcus (1987), and the reference to Aristotle is from the Poetics. The school systems of Italy present Aristotle as a philosophical figure more valuable than Plato due to his realism and appreciation of mimesis, the art of imitation by which we all learn to do the simple things of life, including walking, speaking, and making love. In modern film criticism, neorealismo has often been coupled with populist forms of nationalism that often conceal misogyny and heteronormativity (O’Leary and O’Rawe, 2011). In this study, we offer a new perspective that correlates neorealismo with sexual energy and global ecologies.

- The phrase “Italiani brava gente” comes from the title of a 1965 Giuseppe de Santis homonymous movie that narrates the tribulations of the Italian battalion that joined the Nazi army in the failed 1942 attack on Russia. Retrieved August 27, 2016. https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italiani_brava_gente_(film_1965).

- For more on Giustizia e Libertà, its leaders and significance in Italy and Europe, I refer to Pugliese (1999), and to the relevant Wikipedia entries. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- For a study of “bisexual triangles” in Cavani I refer to Garber (2000). Cavani’s German or European Trilogy is a set of three films she directed between 1974 and 1985. Each film is organized around a “bisexual triangle,” and set at a significant time in German history. The Night Porter (1974), referring to the Holocaust period and its aftermath, inaugurates the series. The bisexual triangle is made of Max, a dainty bisexual man, Bert, a closeted gay man in love with him, and former prisoner Lucia, a BDSM entertainer. Beyond Good and Evil (1978), set in a 1880s Germany at the height of the national unification movement, is about the transgressive, brief, and intense love affair of a homophobic Frederick Nietzsche, a sexually ambivalent Paul Ree, and a maverick Lou Salome. The Berlin Affair (1985), set in Berlin at the height of Hitler’s “purges,” is about the love affair of a German couple imbricated with the regime and the young daughter of Japanese ambassador to Berlin. Each storyline denotes the impossibility of these relationships in a sexual regime of mononormativity dominated by the Oedipal syndrome. The persistence of the trope in Cavani’s work denotes an interest in pursuing the imagination of a world where bisexual triangles coexist with a post-Oedipal sexual fluidity and amorous inclusiveness. For more on this aspect of Cavani’s work I refer to Silverman (1977), Waller (1995), O’Healy (2004), Marrone-Puglia (2000).

- Sexuality is very significant in Bertolucci, by all accounts one of the auteurs most sensitive to the sensuous and lush beauty of nature and human nature in all their forms. A salient trope in Bertolucci scholarship is his erotic slash mentorial relationship with Godard, a mentor in the art of cinema he admired and whose ideological purity he envied. In a cultural scenario organized around the Oedipal syndrome, Bertolucci cannot love his mentor and hate him too. In The Conformist, Marcello is clearly caught in this syndrome. However, Anna Quadri and her husband are not. Quadri invites Marcello to stay in Paris and become part of his activist pod. Anna initiates both Marcello and his wife Giulia to the pleasures and freedom of open relationships, with the consent of her husband. Bertolucci revisits the theme of open relationships in subsequent films including Besieged (1998) and Dreamers (2003), where a bisexual triangle is at the center of the diegesis. Scholars with a special sensitivity to Bertolucci’s ambivalence toward the monosexual culture dominated by the Oedipal syndrome where he evolved as a filmmaker include Kolker (1985) and Micheletti (1995). Kolker reports Bertolucci’s self-deprecating remarks: “I’m Marcello and I make Fascist movies, and I want to kill Godard who makes revolutionary movies and who was my teacher” (215). In A Thousand Plateaus (1987) and Anti-Oedipus (2009), Deleuze and Guattari envision a post-capitalist sexually fluid, amorously inclusive culture of fluxes and plateaus (see also Kolker 185). In this culture, Marcello can enjoy Quadri and his wife Anna, Anna can enjoy Marcello and Giulia with Quadri’s consent, and Quadri can enjoy his wife and his former student. In her discussion of The Conformist, Micheletti openly refers to Anna’s bisexuality and the “primal scene” in which Marcello witnesses her seduction of Giulia (99-101). Micheletti understands Anna as emotionally monogamous and therefore does not envision her amorous inclusiveness.