Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 34 (2018)

We the Affectariat: Activism and Boredom In Anxious Capitalism

A.T. Kingsmith

Abstract: On a political, economic, and social terrain of increasing xenophobia, inequality, and apathy, the project of radical social transformation—collective attempts to shift the set of shared beliefs, ideas, and moral attitudes which operate as a coalescing force within society towards a more egalitarian future—is largely in disarray. This essay probes this decline of transformative politics by locating its disarray in the emergent disconnection between the central focuses and tactics of left politics and the current structures of oppression in late capitalism. As a response to this disarray, it argues for a repositioning of affect—a pre-personal intensity of existential orientation—if radical politics are to begin to close this emerging disconnect. It bolsters such claims by: 1) introducing a framework of affect and its relationship with activism; 2) linking the advent of reactive forms of affect management to the rise of the 'affectariat' in the 20th century, 3) exploring the phenomena of anxiety in conjunction with accelerated capitalism, technology, and a return to moral panic, 4) probing the failure of contemporary activism to respond to anxiety and theorizing some alternative tactics for politicizing affect in a time of increasing democratic malaise.

“Activism has to confront real obstacles: war, poverty, class and racial oppression, creeping fascism, venomous neoliberalism. But what we face is not just soldiers with guns but an affective capital: the reactive society, an excruciatingly complex order. The striking thing from an affective point of view is the zombie-like character of this society, its fallback to automatic pilot, its cybernetic governance. Neoliberal society is densely regulated, heavily over-coded. Since the control systems are all made by disciplines with strictly calibrated access to other disciplines, the origin of any struggle in the fields of knowledge and power have to be extra-disciplinary.” — Brian Holmes, The Affectivist Manifesto>, 2004

“Neoliberalism has exalted the multiplicity of the social actors; it has brought the all-social back to plurality: and now the State, in all its sovereignty and with the anxiety of the general equilibrium, intervenes in every little struggle, in every fragment of movement. Oh, how beautiful this neoliberalism is, allowing us to see the Government as the counterpart of every singularity in the process of struggle!” — Antonio Negri, The Winter is Over>, 2013

Introduction

The 2016 presidential victory of Donald Trump brought more emotion to a US election than that of any previous candidate. There is a startling euphoria among supporters during his rallies—not to mention a unique feeling of fear and anxiety he sparks in liberals, and even in many conservatives. When, at the end of 2016, Patrick Healy and Maggie Haberman of The New York Times analyzed 95,000 words from Trump’s speeches, interviews and rallies, they observed a “pattern of elevating emotional appeals over rational ones,” a tactic also practiced by populist politicians like Joseph McCarthy and Barry Goldwater.

The reason why Trump’s victory—due, as Michael Kazin (2016) points out, to the slow, drawn-out collapse of a popularised left and subsequent rise of a populist right—should be considered an emotional phenomenon is not merely because of the anxious reactions he inspired, but because Trump’s campaign successfully deployed affect to convince Republican (and Democrat) voters that he is an anti-establishment candidate offering an alternative to the status quo—something that (what we will, for the purposes of this article refer to as) ‘the left’ has failed to do for decades.

The ‘left’ has failed to do so because there is an emergent disconnection between the central focuses and tactics of left politics and the current structures of oppression in late capitalism. From the 2011 dismantling of the Occupy encampments in Zuccotti Park to the perpetual dispersion of Black Lives Matter protests in Dallas, the seeming inability of left-leaning social movements to develop viable, populist, long-term alternatives to the destabilizing processes of capitalism is directly related to the left’s failure to respond to the increasing gap between older strategies of action and updated flows of repression.

If the left wants to close this emerging disconnect we argue that a return to affect—that pre-personal intensity of an utmost existential orientation—is crucial. The vital relationship between affect and activism is not a particularly new one. For decades autonomous social and political movements have cohered around communities of action that provide emotional ‘highs’ of excitement and conflict. Pauline Bradley (1997) describes a social struggle as ‘better than Prozac,’ ‘emotionally momentous’ and able to bring about life-changes which drugs, labels, and hospitalisation could not. However, various forms of power seem to have undermined these emotionally reinforcing effects of activism by making the experience of protest feel increasingly disempowering and traumatic.

To probe this disconnect further, we will embark on a series of augmentations that briefly trace the advent of different reactive forms of affect (misery and boredom) which underpin the twentieth century rise of what we call ‘the affectariat’ before exploring the phenomena of anxiety in conjunction with late capitalism, technology, and the present return to a state of socio-moral panic. Finally, we will probe the failure of contemporary activism to respond to such anxieties and theorise alternative tactics for addressing affect management. We take up these lines of flight to highlight the ways contemporary left politics lacks a praxis that will help us undertake the revolutionary task of gradually releasing our repressed visceral and affective desires from the current static realities of neoliberal capitalism—realities such as the NSA, CCTV, performance management reviews, unemployment, financialisation, the privileges system in the prisons, the constant examination and classification of young schoolchildren—a system in which a xenophobic candidate like Trump can manipulate our emotions in order to convincingly present his brand of proto-fascist demagoguery as an alternative to the establishment.

In actively confronting this condition of our collective anxieties, we move to develop a Marxist-Deleuzian framework of affective activism, an approach in which radical affects of active-becoming are contrasted with those of reactive-blockages, to better understand transformations in the structures of oppression and to theorise a next step for activism that seeks to push through the limits imposed by the affective alienation of capitalism in order to replace our position as Oedipualized, defenseless, guilt-ridden puppets in internal straight-jackets, with free, empowered, de-securitised, uncoded subjects equipped with alternative frames that transform our fears into affective projectiles of attack.

Locating an Affective Activism

Marx (1975: 269) wrote the goal of liberation was “the fulfilment of the personality… governed by immediate enjoyment and personal needs.” Augmenting out from Marxist and anarchist thought, activists writing in many traditions—such as Raoul Vaneigem (1967), Gayatri Spivak (1985), Hakim Bey (1994), Feral Faun (1999), and Silvia Federici (2006)—have similarly called for a return to immediacy and viscerality.

Although feeling and affect are routinely used interchangeably, it is important not to confuse affect with feelings and emotions. As Brian Massumi’s (1987) definition of affect makes clear, affect is not a personal feeling. It is a pre-personal intensity corresponding to the passage from one experiential state of the body to another. Affect implies an augmentation, mutation, or diminution in that body’s capacity to act. In other words, feelings are personal and biographical, emotions are social, and affects are pre-personal.

A feeling is a sensation that has been checked against previous experiences and labelled. It is personal, biographical, and largely individualistic because people have (seemingly) distinct sets of lived sensations from which to draw from when interpreting and labelling their feelings. An emotion is the projection or display of a feeling. Therefore, unlike feelings, the display of emotion can be either genuine or feigned.

Affect—what Spinoza (1677) refers to as affection, the capacity to affect and be affected—are non-conscious, transversal experiences of intensity that manifest as dividual moments of unformed and unstructured potential. Of the three existential orientations discussed here—feeling, emotion, and affect—affect is the most ‘abstract’ in that, as Manuel DeLanda (2002) notes, it is a non-conscious, bodily phenomenology that cannot be fully realised in, or reduced to, the sub-stratum of language. Affect is always prior to and/or outside of consciousness. By adding a quantitative dimension of non-reductive intensities to the quality of an experience, affect is the body’s way of preparing for action in a given circumstance. The body, for Massumi (2002: 30), has an intersubjective interface that cannot be entirely captured by semiotics or reduced to language because it “doesn’t just absorb pulses or discrete stimulations; [the body] unfolds contexts.”

At any moment hundreds, perhaps thousands of stimuli impinge upon the human body and the body responds by infolding them all at once and registering them as an intensity. Affect is this intensity—a pure potential—a measure of the body’s readiness to act in a given circumstance. Silvan Tompkins (1995: 88) explains that affect has the power to influence consciousness by amplifying our awareness of our biological state:

The affect mechanism is like the pain mechanism in this respect. If we cut our hand, saw it bleeding, but had no innate pain receptors, we would know we had done something which needed repair, but there would be no urgency to it. Like our automobile which needs a tune-up, we might well let it go until next week when we had more time. But the pain mechanism, like the affect mechanism, so amplifies our awareness of the injury which activates it that we are forced to be concerned, and concerned immediately.

Without affect feelings do not ‘feel’ because they have no intensity, and without feelings transformative political action becomes impossible. In a time of increasing precarity, financialisation, and sweeping neoliberal reforms, affect plays an important role in formulating politically active relationships between our bodies, our environment, and others.

By forcing us to confront the question: ‘What latent thing do you and I, two utterly powerless, simulated individuals, share that might, if activated in some way, endow us with a common sense of things, and from there a collective potency?’ affect reminds us that viscerality is not some sort of authentic self buried by oppression, rather, it is something newly constructed from the wreckage of defeat. And while the proletariat—as a global signifier under which we can converge to transform our societies—may have been dismantled by forty years of globalisation—the affectariat, that is, the existential orientation which non-consciously organises against the fascists in our heads—has the power to transform our approach to social transformation by reminding us: ‘You are not alone in this—in this dead-end job, this bottomless debt, this paralyzing depression.’

The power of affect lies in the fact it is unformed and unstructured (abstract). It is affect’s very real (material) abstractivity that makes it transmittable in ways feelings and emotions are not, and it is because affect is transmittable that it is potentially such a powerful social force. However, as Deleuze and Guattari (1972: 214-17) are at pains to point out, affect functions non-dialectally, as both an active and a reactive force.

When affect is an active force, it can be the drive for social transformation. Affect enables groups of subjects to arrive immanently at dissident positions that may shed light on non-totalitarian alternatives to the status quo. When it is a reactive force, in contrast, affect has its origins in statism and capitalism. It aims to make social space neat and orderly by creating and recreating governable subjects that are conducive to top-down quantification and control whilst simultaneously providing the work-discipline and speed which capitalism demands. Reactive force relies on bodily, emotional and sexual repression, which operate through what Deleuze and Guattari (1972: 350-51) refer to as “a restriction, a blockage, a reduction.” When (as now) reactive force is prominent in the social field, social movements are frequently confronted with more and more impasses.

Reactive force should be theorised in continuity with alienation and decomposition because ultimately, through being disempowered and segmented, reactionaryism is active force turned against itself. Processes of alienation convert active into reactive force, attacking the field of abundance and creating a situation of scarcity that is continually reproduced. In reactive systems, the active forces of a politically empowered and affectively cognizant citizenry are disjointed so as to prevent our flourishing, budding, or connecting to one another. Hence one ends up with a rapidly decomposing post-fact, post-truth, post-shame political order like ours—an order which actively denies life, but keeps bio-politically force-feeding survival and stimulation to a near saturation point.

In their ground-breaking study of the relationship between panic and ideology, Arthur and Marilouise Kroker (1990) chart the ways in which the technological imperatives of modern science and the social demands of popular culture have fused into a hypermodern reality that oscillates between reactive extremes of deep anxiety and giddy euphoria. “Vibrating between poles of despair and ecstasy, the central tendencies of postmodernity may be characterised as a catastrophic implosion of the languages of modern power into a dense and high speed oscillation between meaning and meaninglessness, control and chaos, increased centralization and an orbital spin into abstract and disembodied codes of information,” (1990: 443). Central to the present social situation is this profound paradox in which we are forced to be at home in both the prison house and the pleasure palace.

As the Institute for Precarious Consciousness (IPC, 2014) points out, this antagonism of social, political, and technological forces has been central to radical perspectives for quite some time. We can think of active and reactive force as the social and political principles of anarchist Peter Kropotkin (1896), the affinity and hegemony of Gramscian Richard Day (2005), the constitutive and constituted power of autonomist Toni Negri (1999), the power-to and power-over of sociologist John Holloway (2002), the instituting and instituted imaginaries of psychoanalyst Cornelius Castoriadis (1997), the feminist terms of reproductive labour and its alienation, the eco-anarchist terms of wildness (abundance) and civilisation (scarcity), the poststructuralist terms of productive textuality and the closed text, and even in Buddhist and Taoist terms of life-energy and its illusory forms.

So why are reactive forces, which gave rise to Trump in America, Brexit in the UK, Duarte in the Philippines, and Modi in India, (to name a few), so prevalent today? To answer this question, the mutations of active and reactive force under different phases of capitalism need to be probed. According to the Marxist-Deleuzian framework of affective activism articulated by contemporary theorists such as Athina Karatzogianni, Andrew Robinson (2010) and Brian Massumi (2015), each phase of capitalism has a dominant reactive affect, which is particularly induced by its dominant forms of power—especially in its core regions. In the nineteenth century, the dominant reactive affect was misery; in the Fordist period, boredom; in the neoliberal period, anxiety. Importantly, this is not a static situation. As capitalism is always redefining its own limits, it constantly comes into crisis and recomposes and reterritorialises around new affects—as its power comes largely from its alienating force, the pervasiveness of a particular form of dominant affect management only lasts until strategies of resistance can break down its social source.

This notion of three dominant reactive affects put forward by affective activism parallels Richard Day's (2005) distinction between old, new, and newer social movements. From misery to boredom to anxiety, each phase personalises the dominant reactive affect, blaming the oppressed for their oppression. This is reinforced by social isolation, and by systems of distraction (self-help, consumerism, etc.). According to the writings of the Situationists (2006), every phase of affect management under capitalism is a public secret—something that, though everyone knows and experiences, nobody publicly acknowledges or talks about. As long as the dominant affect of anxiety is a public secret, it remains effective, and strategies directed against its sources cannot emerge.

Thinking of capitalism as a mode of managing our dominant affects presents an alternative to theories that celebrate the rise of immaterial labour—labour that produces informational and cultural content as commodities—as a path to eventual liberation through the unleashing of human creative power. Theories of immaterial labour wrongly assume that capitalism releases human creative potential and that the main problem is merely the privatisation of its product. In other words, they locate the problem not in the processes of capitalism itself, but rather in the ways in which it commodifies outputs.

If capitalism is conceived of as a mode of reactive affect management it clearly does not release human creativity in new forms so much as it traps them in anxiety through a compulsion to communicate in terms of artificial social performances grounded in the dominant system's terms. Simply put, alienation is internal to the functioning logics of late capitalism, not merely the exploitation of its production. For example, presently the dominant narrative suggests we need to take on more stress to keep us ‘safe’ (through securitisation) and ‘competitive’ (through performance management). Each moral panic, crackdown, or new round of repressive laws adds to the cumulative weight of anxiety and stress arising from general over-regulation. Real, human insecurity is channelled into fuelling securitisation. This is a vicious cycle because securitisation increases the very alienation (surveillance, regulation, conformity), which causes anxieties in the first place.

The ways in which capitalism reinforces vulnerability and disposability are illustrative of this alienation. It keeps us fragmented and disillusioned by personalising responsibility for collective crises like rampant inequality and global warming. Instead of being urged to confront the sources of these social ills—for example, the fiscal servitude imposed on the Global South by outrageous IMF loans or a steadfast commitment to expanding fossil fuel capacities—we are told to keep calm, donate to charity, participate in what one New York Times journalist (2016) calls ‘voluntourism’ projects, recycle, refrain from watering the lawn on weekdays, and compost kitchen scraps. All of this is further reinforced by a self-esteem industry that tells people how to achieve success through positive thinking, as if the sources of anxiety and frustration are simply illusory. Philanthropy, therapy, and the self-esteem industry exemplify the ways in which problems that are directly related to our socio-economic reproduction are re-framed in alienating terms of individual psychology.

In a similar way, public secrets are typically individualised. The problems of boredom and anxiety—those familiar, unpleasant ruminations informing psychosomatic turmoil—are only visible at the personal level, their social causes remaining concealed. In other words, each phase of capitalism blames the system’s victims for suffering the system causes. As a result, capitalism vindicates its violences by portraying the fundamental part of its functional logic as a contingent and localised problem—in the same way that capitalist logics fault the poor for their poverty, it blames the depressed for their anxiety.

By rejecting the internal attribution of blame and the individual orientation of therapy, affective activism emphases social oppression and collective responses. This perspective can transform the anger and alienation resulting from the oppressive experiences of capitalism into a more positive, focused kind of discontent. In situating the problem of anxiety socially (as opposed to individually), affective activism affords us the collective creativity to feel anger, both as subjects and as a collectivity, which can overcome earlier prohibitions by making anger an energising force for change, increasing confidence, and enhancing activist relations and coalitions against power.

The Rise of the Global Affectariat

The ‘left’ always seems to flock to questions of ‘who’ and ‘how.’ Who are the vital agents of history? How will global social transformation come about? Right into the late twentieth century, the proletariat occupied the position it did in Marxist thought not because of some sort of a priori proletarian virtu, but because a large majority of Marxists argued that industrial workers (‘the who’) occupied a fundamental position in society that equipped them to transform it (‘the how’) and to lead other social elements in doing so.

The ‘first wave,’ or the ‘old’ social movements characterised by the general strike, were directed against a proletarian context in which misery was the dominant reactive affect. Concealed by capitalism, this misery was revealed by political theorists such as Marx (1857) himself, who saw immiseration as a central impetus for the improvement of the proletarian experience. The movements of this era were machines for fighting misery through wage and welfare struggles for mutual aid. The defeat of misery by the first wave of social movements caused capital to migrate to a new strategy based on boredom.

This dominant affective switch from misery to boredom was made possible in large part due to a mid-twentieth century economic boom—a time during which much of the left was forced to confront the reality that labour leaders (specifically in the United States and Western Europe) were more interested in advantageously positioning themselves on the terrain of power than in leading social change. In other words, the cooptation of the ‘responsible’ elements of the labour movement through institutional reforms and mass consumption was supplanted by the fierce repression of more ‘irresponsible’ elements.

In the case of the United States, the radical and communist left were swiftly purged from the ranks of organised labour. This process began in 1947 with the Taft-Hartley Act’s ‘loyalty oaths’ and culminated in 1949 when communists and alleged sympathisers were excluded from the Congress of Industrial Organisations (CIO) executive board—eleven unions representing more than a million workers were purged from the CIO ranks. In Western Europe, reformism and repression also went hand in hand as the newly designated ‘responsible’ US labour leaders were invited to assist the US government in the postwar reconstruction of Western Europe by setting up new non-communist unions in direct competition with the existing trade union movement. Thus, while great material rewards awaited more ‘responsible’ union members who stuck to the politics of mass consumption, a period of intense repression—culminating in McCarthyism—awaited the ‘irresponsible’ ones who rejected the parameters of the new hegemonic compromise. The defusing of the revolutionary challenge posed by core labour movements was therefore accomplished through the potent combination of intense repression and co-optation.

Of course, neither of these mechanisms would have succeeded in replacing misery with boredom as the dominant reactive form of affect without some fundamental transformations in the structure of business enterprises—that is, the global spread of US corporate capitalism. The wave of US corporate investments in Western Europe in the 1950s and 60s, in combination with the European response to the ‘American Challenge,’ fostered the rapid spread of Fordist mass production techniques in Western Europe. The end result was a weakening of the strongest segments of labour in both Western Europe and the United States from which the movement has never recovered.

On the one hand, as mechanised wide-scale production techniques spread in Western Europe, artisans and craft workers—who had been the backbone of militant European labour in the first half of the twentieth century—were increasingly marginalised from production and thus their bargaining power was undermined. On the other hand, as the geographic relocation and reorganisation of US corporate capital proceeded, the semi-skilled mass-production workers who had previously formed the backbone of the US labour movement in the 1930s and 40s were progressively and relentlessly weakened.

These combined methods of repression and restructuring overcame the anti-capitalist challenge against the dominant affect of misery mounted by the early twentieth century labour movements in industrialised countries. By the 1950s and 60s, according to Ross and Hartman (1960), this transition was referred to as ‘the withering away of the strike’ by industrial sociology literatures—due to a shifting of the socio-economic terrain towards increasing processes of Fordist, Taylorist modernisation based on secure, decently paid but monotonous work that created an experience of a ‘flat’ world with no outside.

While it was unavailable to everyone, the ‘B-worker deal’ of boredom for security underpinned this phase. As early as the late 1940s, boredom began to fully replace misery as the public secret. However, apart from exceptions such as Walter Benjamin and Theodore Adorno, boredom was not recognised as a problem until the 1960s—when the malaise of relentless consumerism and slowing growth brought to the fore discourses which pointed to the newly minted public secret. The inadequacy of existing social movement tactics—such as forming Leninist parties, staging simple A-to-B marches, and calling public meetings (usually denounced as boring in their own right)—linked to their inadequate operation as misery machines fighting against boredom.

Interestingly, in his analysis of power in the twentieth century Giorgio Agamben (2004: 70) defines this “profound boredom” as the state of suspension through which living beings awaken to the fundamental reality of their captivation. It is this awakening—this anxious and resolute foreclosure that characterizes life in late capitalism—that leads Agamben to conclude that boredom-as-tactic is the non-relational estrangement of our relationship to our life-affirming preoccupations and our captivated relations with our environment.

For their part, the Situationists (1967: 18) advanced the claim: “[w]e do not want a world in which the guarantee that we will not die of starvation is bought by accepting the risk of dying of boredom,” while feminist theorists like Betty Friedan (1963: 37) probed at the existential root of malaise and depression among newly relegated housewives: “I do not accept the answer that there is no problem…it cannot be understood in terms of age-old problems of…poverty, sickness, hunger, cold. The women who suffer this problem have a hunger that food cannot fill.” In many ways, the critiques put forward by Situationism and Friedan can be seen as two in a series of similar approaches—critical pedagogy, theatre of cruelty, militant inquiry, countercultural aesthetics, sit-ins, protest camps—attempting a general exodus from the dominant forms of (boring) work and social roles.

While these resistances to Fordism partly succeeded in creating temporary spaces where emancipatory modes of though could spread, capitalism again reconsolidated power under the new reactive affect of anxiety—chasing the mass exodus of the 1960s countercultural revolution by subsuming the whole of the social field through practices such as flattened hierarchies and niche markets. Emboldened by the stagflation of the 1970s, the intensification of attacks on workers in the 1980s was the opening salvo of an accelerated neoliberal project championed by Regan, Thatcher et al.—a project which worked to, once and for all, eradicate, enclose, and recuperate the extra-work spaces where radical exoduses fled as sources of value and production.

As a global system that redefines citizens as consumers whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling on a market which delivers benefits that could allegedly have never be achieved by planning, neoliberalism has gone further than ever before towards permanently entrenching a newly dominant affect of anxiety at an even deeper level at home—reaching out, not unlike Trump today, to core working class groups with more promises of mass consumption—while simultaneously confronting the escalating demands for independence and social justice in the ‘under-developed world.’

After all, the successes of national liberation movements in India and (especially) China eliminated any remaining doubts in the minds of US policymakers about whether capital reforms could be limited to the core. To them, it was becoming quite clear that the longer national liberation struggles dragged on, the more likely they were to spark larger social revolutions. Just as the affective labour-capital conflict between workers and owners was recast as a technical problem of Keynesian over taxation alongside increasing growth and productivity, so, as Arturo Escobar (1995: 33-34) points out, US neo-imperialist dictums such as Truman’s ‘Fair Deal’ worked to recast and reframe the North-South conflict as an entirely technical problem that was amenable to a wider and more vigorous application of the modern scientific and technical knowledge of capital:

In the late 1940s the real struggle between East and West had already moved to the Third World, and development became the grand strategy for advancing such rivalry and, at the same time, the designs of industrial civilisation…The fear of communism became one of the most compelling arguments for development. It was commonly accepted in the early 1950s that if poor countries were not rescued from their poverty, they would succumb to communism. To a greater or lesser extent, most early writings on development reflect this preoccupation.

As a result, the possibility of affective upheavals in the developing world, were met (and defused) through the decolonisation and expansion of the Westphalia system. Legal sovereignty was extended to all nations and enshrined in the charter of the United Nations—where the revolutionary potential of an expanded system of sovereign states could be effectively defused through safeguards such as great power vetoes and permanent seats on the Security Council. Moreover, just as voting rights were skewed in favour of the Western powers (like the old network of the League of Nations) so too, control over the new institutional guardians of the world economy (IMF and World Bank) were weighted in favour of the largest contributors—the rich countries of the world.

Thus in many ways, the concept of development emerged alongside the transition from misery to boredom after the post-war compromise of the 1950s—a US response to the need to offer leadership in a world in which the political weight of Asia and Africa suddenly loomed large—and accelerated with the anxiety-driven neoliberal project of bringing newly independent countries into the global market (and thus under the purview of World Bank and IMF structural readjustment loans). The hegemonic compromise put forward was that with hard work, all the peoples of the world could achieve the ‘American Dream’ by passing through a similar set of stages of development before arriving at the ‘Age of High Mass Consumption.’ The reality, however, was not the universalisation of a high standard of development—a standard which the North itself has not yet fulfilled—but rather the exportation of reactive forms of affect management to more and more people.

Charting the Terrain of Anxiety

Social movements from the 1980s onwards have been faced with the new, neoliberal composition of reactive affect, but this composition has only gained coherence over time. The Invisible Committee (2009: 31) suggests we are kept in a “chronic state of near-collapse,” which is a public secret, while ‘Bifo’ Berardi (2009: 43) adds that multiple anxieties are fuelling a “global panic.” Crucially, this reactive anxiety is generalised—even to the excluded and self-excluded. This weakens the strategies of exodus that undermined the regime of boredom. Simultaneously, anxiety is also personalised: from New Right discourses blaming the poor for poverty, to contemporary therapies which treat anxiety as a neurological imbalance or a dysfunctional thinking style, a hundred varieties of management discourse—time management, anger management, parental management, self-branding, and gamification—all offer anxious subjects an illusion of control in return for ever-greater conformity to the capitalist model of subjectivity.

Anxiety is not just an emotion. Nor is it a symbolic phenomenon. For Jacques Lacan (2014), anxiety is the affective response of a subject being confronted with the trauma of the ultimate dislocation, fragmentation, and decomposition of their identities. Anxiety cannot be symbolically articulated because it is situated at the border between the imaginary and the real—between the phantasmic (narcissistic) and the body. Thus anxiety is not just a question of repression, but of the threat of perpetual deconstruction—the object of which is the permanent (re) inscription of all meaningful signifiers.

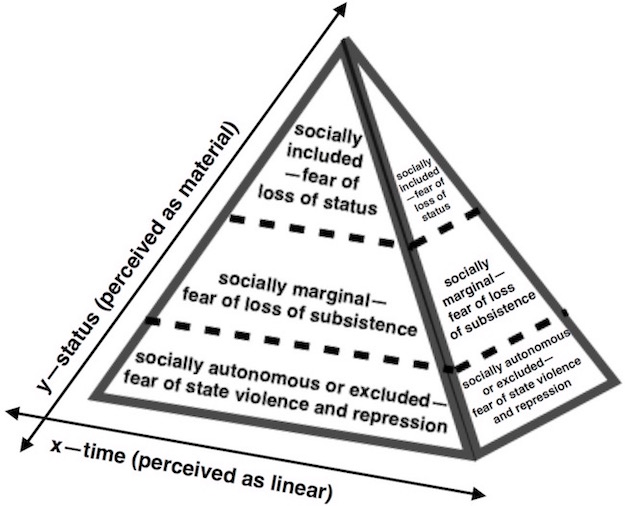

It is important to note that the psychosomatic deconstruction wrought by anxiety is experienced differently across distinct socio-material registers—class, race, gender, ability, sexuality, etc. With the diversity of the extra-subjective experience in mind, Brian McMarvill and Rob Los Ricos (n.d.) make a useful distinction between three variations of anxiety (see Figure I below). For the socially included—anxiety comes from the fear of loss of status. For the socially marginal, fear of exclusion and the loss of subsistence. For the socially autonomous and excluded, the fear of state violence and repression. As a result, people are deemed disposable in that violent tactics can be used against anyone—even privileged subjects—without entailing any systemic illegitimacy.

This limitless disposability creates a perpetual feeling of powerlessness, when people are not in fact powerless. For example, in his studies of unemployed, precarious, and marginalised youths in Eastern and Western Europe, Bifo (2009) suggests that they are often as hopeless about rebelling against current structures as they are about getting work because the desire for 'something more' has been corroded. Hence, anxiety and the resultant feelings of powerlessness seem to undermine the germ of resistance.

Of course, discussions of powerlessness and anxiety are not new. In 1844, Soren Kierkegaard explains anxiety as the dizzying effect of noise, of paralyzing possibilities, of the confrontation with supposedly boundlessness selection—“a kind of existential paradox of choice,” (1844: 34). Analogously, Martin Heidegger (1927) conceptualises anxiety as an indeterminate state of being anxious about nothing in particular—anxiety is experienced in the face of something completely indefinite. Both Kierkegaard and Heidegger’s respective conceptualisations of anxiety are resultant of the transition from a state of non-conscious immediacy to self-conscious reflection—what Jean-Paul Sartre (1943) calls pre-reflective and post-reflective consciousness. In other words, anxiety is the disjuncture produced through the semiotic bombardment of exponential increases in banal (consumer) choices coupled with a decrease in meaningful political alternatives.

In the 1930s, as fascism began to take hold across Western Europe, William Reich theorised anxiety as the result of a conflict between the libido—unconscious desire—and the outer world. What is new about capital’s management of affect under neoliberalism is that anxiety now globally subsumes the whole of the social and emotional field, rather than being concentrated in specific spaces such as sexuality. In other words, we cannot mitigate the problem of anxiety in industrialised societies by suggesting that people were always anxious. As the Institute for Precarious Consciousness (2014) points out, to do so is to conflate the particular neoliberal regime of generalised, reactive anxiety with a much broader category of precariousness or potential vulnerability. Dominant periods of misery and boredom involved vulnerabilities that provoked anxiety. The point is precisely that social movements have strategies proven to defeat many of those older forms of vulnerability, but that these strategies are not as effective in the present period due to the general spread of anxiety across the whole of the social field as a means of control.

There are various mechanisms for this total subsumption of anxiety. Professionalised networking permits communication only along systemically mediated paths; existence becomes reduced to 140 characters or less, and that which cannot be communicated within this limit is systematically excluded. The internalisation of these mechanisms leads to self-surveillance and self-association with quality metrics and social media networks. This requires that people be communicable on dominant terms by way of a bureaucratisation of everyday life under regimes of risk-management, consumerism, and securitisation—all of which require particular social performances that, rather than being hedonistic, compel people to keep up the appearance of happiness and participation.

More than ever, public spaces are subject to growing forms of surveillance and regulation—research by Anna Minton (2012) confirms that security measures such as CCTV and gating intensify anxieties—while risk-management and securitisation impede alternative practices by directing our behaviour in increasingly innocuous ways. Moreover, as Greg Ulmer (2005) points out, on a post-9/11 terrain even our monuments—those processes of collective memorialisation that encode ideal values and forms of behaviours on citizenries—have become subsumed by ‘increasingly hysterical narratives of fear and anxiety.’

Reactive force in neoliberalism functions through an obligation to be communicable, distinct from the prohibition on speaking of earlier periods. Paul Virilio (1977) refers to this reactive phenomenon as telepresence, or the immediate presence of different spaces to one another. Telepresence causes generalised vulnerability to the gaze of others. The result is a political terrain hindered by a culture of groundless consumption and re-consumption underpinned entirely by anxious social performances that, rather than producing sites of creativity and empowerment, compel people to keep up appearances of productivity and enthusiasm in order to maintain their position in a social hierarchy.

Of course, it is always tempting to locate the blame for our total anxious subsumption on technology. If an idea is clickable, it will feed into existing prejudices. This is the nature of a networked society. As the Invisible Committee (2014) points out, supraliminal algorithms curated by Facebook and Google are now based largely on our previous search histories. Social media, now the primary news source for most of the connected world, have pushed us deeper into an echo chamber of interpretation, wherein every version of an event is just another narrative and lies can be excused as an alternative point of view or an opinion, because it’s all relative and everyone has her own truth.

Yet it is important to remember that social media platforms are merely a means through which the dominant reactive affect is being distributed. This desire to take shelter in a personal techno-fantasy is a symptom tethered firmly to an underlying economic, social, and political set of anxieties which have manifested as an impending sense of uncertainty that has spread from individual registers into the whole of the social field. After all, if the empirical data says: ‘you have no economic future,’ ‘the environment is deteriorating at an unprecedented rate,’ ‘and traditional sources of stability and security such as the state and market are culpable in all of it,’ why would you not want to retreat into a curated, striated, and de-politicised space? If you live in a world where political instability in Central Asia leads to the loss of livelihoods in Detroit, where governments seem to have no control over what is going on, public trust in the institutions of authority—politicians, academics, media—buckles under the weight of our collective uncertainty.

Economically, as Bifo continues (2009: 75-7), anxiety is linked to global outsourcing, lean production and financialisation. Indeed, there is a material isomorphism between generalised anxiety directed towards the future, and an economy with an explosion in the quantity of a fictitious, speculative capital in circulation that lacks any prospect of redemption in the real economy. As a result, we who are subjected to anxiety—while experienced at different levels of loss (status, substance, and/or violence)—can be thought of as a kind of affectariat. This focus on affectarity is an attempt to suggest that anxiety is a socially manufactured affect, rather than a personal deficit or individual difference. As Brian Holmes (2003) points out, affectarity is ‘non-self-determined insecurity’ across work and life with insecure access to the means to survive or flourish.

Affectarity is a reaction that uses affective insecurity to impose normalisation. It treats people as disposable—operating by rendering people’s lives ‘contingent on capital.’ Unlike the socio-economic limitations of a term like precarity, affectarity points to the ways in which the violences of anxious-late capitalism permeate through all of conscious, unconscious, and non-conscious life. The anxiety imposed on the affectariat leads to constant bodily over-stimulation and excitation that traps us within a socially imposed impossibility of relaxation that lacks any tangible means of actual affective release.

As the Situationists remind us however, this situation of generalised anxiety and stress is a public secret, not widely recognised in officially tolerated discourses. Research by Beat Weber (2004) suggests that most workers are unstable—psychosomatically, corporally, materially—yet reluctant to admit it due to of social taboos. Recent data collected by the Public Religion Research Institute (2017) corroborated Weber’s hypotheses, finding that a ‘culture of anxiety’ was by far the most common reason given by voters who switched from Obama in 2012 to Trump in 2016. After all, anxiety, depression, attentive stress and so on are recognised, but only as personal problems, explained away as neurological problems, faulty cognitive schemas, or a lack of coping strategies. Indeed, the public transcript suggests that we need more stress and anxiety, so as to keep us ‘safe’ and/or ‘competitive.’ Part of the public secret is related to the fact that dominant discourses—prevalent in media, advertising, and popular culture—continue to assume the normality of Fordist life-courses and expectations, against which affectarians necessarily fail.

Just as earlier forms of capitalism used national growth as a vicarious substitute for real welfare, and later foreign wars as a channel for boredom-induced frustration, so today real insecurity is channelled into support for securitisation. For as Arjun Appadurai (2006) points out, the intolerance of in-groups is a way of acting-out anxiety over the collapse of boundaries in the era of exacerbated globalisation. Often, today's crackdowns—such as the increasing moral panics and anti-immigration ideologies on the rise in the majority of ‘democratic’ states—seek to uphold the structure of Fordism—i.e. nationalism, community integration, ‘respect,’ etc.—in a context where the infrastructure is long-gone. Thus we have reached a vicious plateau where, as securitisation continues to intensify the sources of insecurity, more people will die during the period of a normal week than would during a month of social upheaval, and relatedly, more insecurity is caused in a normal week of securitised harassment and disposability than in a month of demonstrations.

Responding to Anxiety in the 21st Century

During active periods of mobilisation such as the May 1968 student’s movement people felt a sense of empowerment, an ability to actively express themselves, a sense of authenticity and de-repression or de-alienation that acts as an effective treatment for psychosomatic despondency. A similar kind of affective plateau, the contagious opening of previously unimaginable political possibilities, however impermanent, is what is needed in order to activate radical alternative tactics and strategies over the long term.

We can refer to this moment as what some radical feminist epistemologies call the click, that is, the moment in which our societal inequities are realised. The click is the instant at which experiences and feelings suddenly make sense in relation to the repressive bureaucracies of capitalism—something quite different from conceptualising structural violence in the abstract. Afterwards participants feel that they know the impact of affect management, that they have an active, affective answer to the ‘why?’ of resistance.

This is crucial for the emotional transformation of anger and fear into a sense of injustice, a type of empowered anger that is less resentful and more focused, a move towards self-expression, and a reactivation of resistance. ‘The click’ brings about validation and focus to our reactive anxieties, a focus which is different from the hopelessness and frustration experienced previously in that it exercises voice, it moves the reference of truth and reality from the system to the speaker, contributing to a reversal of perspective—a reversal in which we see the world through our collective positions and desires, rather than through the limits of a one-dimensional system.

Such experiences have become rarer in recent years. Anxious individuals are faced with immense difficulties in acknowledging their reality and pain in a world in which something must be counted by ‘quality’ regimes or mediated by television, the Internet, or the media assemblage to be validated as ‘real.’ Many of the affectariat are unaware of the fact that they belong to an oppressed group because the repressive bureaucracies of the society of control have become normalised and their psychological effects personalised. The unacknowledged nature of anxiety as a public secret within dominant political, economic, and social discourses further reiterates this point.

Social movements today do not have the proper mechanisms in place for combating anxiety. Calls for deliberate exposure to high-anxiety situations—physical confrontations with the police, open marches in the streets—are indicative of the reactionary indisposition of contemporary social movements towards anxiety. For example, a traditional tactic, what activists call the “do-ology,” is that of the vague injunction, “Just stop being afraid!” Yet anxiety is not simply the spectre haunting action. It is a material force—the psychoanalytic apparatuses of control are very much material. The question of overcoming the spectres of anxiety is rarely as simple as consciously rejecting it.

The intensified securitisation of the surveillance state makes this process of recognition and resistance even more difficult as dominant affect management takes on the form of pre-emptive control techniques that stop protests before they start or before they can achieve anything. Kettlings, mass detainments, stop-and-searches, lockdowns, pre-emptive arrests, group infiltrations, and practices of disposability, such as violent dawn raids and unmitigated police brutality, are all examples of these kinds of tactics.

What’s more, psychosomatic torture techniques—‘punishment by process,’ as Michel Foucault (1977) terms them—keep individuals fearful and feeling vulnerable through the abuse of procedures designed for other purposes, such as keeping people on pre-charge or pre-trial bail conditions in order to disrupt their everyday activities, using no-fly and border-stop lists to harass known dissidents, needlessly putting people’s photographs in the press, arresting people on suspicion, using pain-compliance holds, or quietly making known that someone is under surveillance. While fear of state interference has been a tactic of control for centuries, today such tactics are inflated and reinforced by an ever-expanding web of visible surveillance gridded across public space which acts as strategically placed triggers that re-enforce fear, trauma, and anxiety.

Needed now are not just better tactics for confronting pre-emptive control or circumventing psychosomatic torture. Needed are long-term strategies for disrupting this lynchpin of subordination. Needed are active machines for combatting anxiety.

This is something which does not yet exist, because what the Situationists (2006) call a reversal of perspective has yet to be accomplished. Today’s main forms of resistance are largely ineffective precisely because they are based in reactive struggles against previous forms of affect management. But these old strategies are no longer working. Power has mutated, and as a result, any political project that is not open to confronting this global event of anxiety is doomed to be incapacitated by anxiety’s everyday fervour.

Most of the strategies employed by current social movements tend to mirror what has worked in the past. Strikes, wage struggles, co-operatives, partisan political alternatives, street protests, the refusal to work, working to rule, and occupying various public spaces have proven to be highly effective tactics in combating earlier manifestations of affect management, but they are largely ignorant of the ways power is modularised today.

Take Occupy’s attempts at capturing Zuccotti Park and other public spaces. Occupy failed to initiate lasting socio-economic change through its actions. Moreover, its anti-corporate messages were subsequently coopted by the partisan machine of Democratic presidential hopeful Senator Bernie Sanders. As Andrew Conio (2015) points out, Occupy’s failure was due, in large part, to its unwillingness to alter its tactics to confront the affective anxieties produced by the ubiquitous surveillance machine operating at the core of late capitalism. Public spaces where people can engage in free speech and assembly unobstructed by state and corporate power do not exist anymore.

For example, when Black Lives Matter occupied a Minneapolis police station, their movements were surveilled and recorded by a dozen adjacent security cameras. When rioters in London occupied their neighbourhood streets and shops to protest the police shooting of Mark Duggan in 2011, the state stood aside, let the riots run their course, and then proceeded to round up over 5000 people by cross-referencing their actions with thousands of hours of CCTV footage. And when a pro-Palestinian demonstration broke out in Toronto in 2012, police were able to intercept and shutdown the march by following the detailed instructions posted by organisers on various social media sites.

What has self-securitised actions such as these is the gap between radical processes of thought and traditional practices of action. Simply put, though Occupy and other recent social movements continue to illuminate the ways in which late capitalism is deployed as power for violating populations according to dominant socio-material logics controlled by white, wealthy, masculine, minoritarian groups, their mobilisations take place on a plane of traditional tactics. They protest, march, and occupy—all strategies which have been proven less effective in our securitised climate of anxiety as the dominant affect. Such strategies still matter—they continue to prove essential for building solidarity through and across groups and movements—but their political referents are no longer sufficient in the affective struggle to de-mystify and dismantle the public secret of anxious capitalism.

We must re-direct our energies towards creating active configurations of sufficient power for interrupting the dominant construction of anxiety; a reversal of perspective, a unifying break, a click, a moment in which it is realised that tactics must be immanent to thought. While traditional tactics can and still work effectively against more traditional forms of violence and repression, an affective activism can help to directly confront our anxieties by conveying that it is ‘good’ and ‘positive’ to express our viscerality, to be collectively angry and to convey anger every time we confront the affect management of capitalism.

Such a visceral emancipation is crucial in transforming our anxiety into active forces that enable re-composition, such as love, courage, laughter and focused anger. As a result, the consciousness-raising processes of affective activism are psychologically positive in untying knots and releasing active force because they allow for a recognition of anxiety as a social affect reinforced through rhetorics of performance management. In turn, this recognition can shift perceptions of the social field from a game of competitive success to a conflict scenario and a narrative of oppression and liberation.

According to Antonio Negri (2013) such a vector of contemporary struggles is most likely to materialize (on urban, industrialized terrain) as a sort of general metropolitan strike—a totalizing confrontation of capital in the sphere of circulation, that is, not at an increasingly unlocatable point of production but in the metropolis, the site where life and work tend to pass over into one another in an economy increasingly defined by immaterial, precarious work in the tertiary (or service) sectors. “To attack the global form of power is to affect the entire chain of production,” (2013: 12). For Negri, to engender this diffuse form of activism means the deployment of a range of tactics disseminated outside of traditional strategic horizons. Simply put, to take terrain means not just to seize the city at its crucial check-points—in order to overturn existing forms of power—but to render the city ‘untakeable,’ a diffuse production of subjectivities that are affectively ungovernable under previous logics.

In other words, as work by the IPC (2014) and others has been at pains to point out, developing an affective activism of active-becoming as resistance against the dominant form of neoliberal affect management requires a grounding which acknowledges that:

- The transformation of reactive affects into movement-focused anger and courage is only viable through large reconfigurations of horizontal connections that stave off both meaninglessness and isolation;

- Modern reactive anxiety and its resultant feelings of powerlessness actually contain the transformative potential for active resistance to capitalism because anxiety and related emotions (depression, frustration, trauma, excessive stress, etc.) provide a clear focus needed for organising.

After all, Donald Trump won the election in large part because he was able to get an unexpected number of centrist and left-leaning votes. As has been discussed at length in mainstream and alternative US media, this swing cannot be entirely explained by the widespread and instantaneous resurgence of racist, xenophobic values in the American electorate because, in many ways, Trump’s anti-establishment platform appealed to the affectariat—we precarious, anxious people who are looking for alternatives (as Obama’s gleeful rhetoric of ‘hope and change’ did so effectively in 2008, and again in 2012).

Of course, Donald Trump is vehemently establishment—as Paul Waldman (2016) of The Washington Post points out, Trump’s newly appointed 'anti-establishment' cabinet owns more wealth than the annual GDP of 87 countries—but the point remains: reactive forces (such as the aforementioned forces which gave rise to events such as Brexit and the stunning victories of Modi and Duarte), are prominent today not (entirely) because of a grassroots shift to the right, but because the reactionaryism of right-wing forces continues to offer an anti-establishment alternative (however illusory) to desperate affectarians willing to try anything new to alleviate their anxieties—as Appadurai (2006) reminds us, such reactions always feed the very anxieties people wish to alleviate.

In an age of anxiety, building social transformation on the left requires a turn towards active and affective activism—anger over fear, collectivity over anxiety, anticipation over sadness. At our current preliminary state, such reconfigurations require:

- Producing new non-dogmatic theories relating to experience (our own perceptions of our situation are blocked or cramped by dominant assumptions, and need to be made explicit);

- Recognising the reality and the systemic nature of our experiences (we need to affirm that our pain is really pain, that what we see and feel is real, and that our problems are not only personal);

- Transforming emotions (people are paralyzed by unnameable emotions that need to be transformed into a sense of injustice);

- Creating expressive voice (the exercise of voice moves the reference of truth and reality from the system to the speaker, contributing to the reversal of perspective—seeing the world through our extra-subjective and dividual perspective and desires, rather than the system’s).

The point of an affective activism is not simply to recount experiences but to transform and restructure them through their transversal theorisation. Participants change the dominant meaning of their experience by mapping them with different assumptions. This is often done by finding patterns in experiences that alleviate anxiety by providing political awareness of the origins of affects while simultaneously gesturing towards the power of group support. Beginning by seeing personal problems and small injustices as symptoms of wider structural problems has the power to initiate the ‘frightening’ (active) as opposed to the ‘frightened’ (reactive) characteristics of a politically salient affectariat.

As Andrew Robinson (2009: 174) warns in his work on the crises of left politics and social transformation, “we are scared to experiment, scared to dream, scared even to hope for something better for fear of invoking the dread totalitarian spook of the utopia that is One, singular and thus all-encompassing and intolerant of difference.” Simply put, one of the causes of immobilism on the left—due, in part, to the affective reverberations of the 'failed experiments' of the twentieth century—is a resistance to developing new tactics for new terrains. Social transformation need not be theorised as a break or rupture in an otherwise crystallised or omnipotent system. New energies are present in this system as lines of flight, leakages that remind us systems are always something being produced, systematised. Our energies are the result of an ongoing affective process—one this is always incomplete and imperfect. Movements evade, they temporarily evacuate various controls and captures, and this energy—itself propulsive, constituting, instigating—is what we need to generate.

Social movements are only a frightening force against affect management when they do not succumb to anxiety. Moving forward, we must work toward providing an alternative to processes that begin and end with the development of critical capacities, as well as to approaches that funnel critical development into traditional organisations. Of course, the approach put forward here is but the possibility for affective transformation in a context where the left seems largely blocked. Ultimately, the process of formulating new strategies is experimental and unpredictable. But by reconnecting with our experiences now—rather than theories from past forms of affect management—recognising the shared, systemic nature of our experiences, and working to transform emotions and construct dis-alienating spaces by unifying through patterns in our shared experiences, affective activism is a form collective care that has the potential to mutate into affinity groups within a wide network of autonomous organisations that have the critical and tactical capacities to move away from reaction and towards active social transformation.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor. 1974. Minima Moralia. London: Verso.

Agamben, Giorgio. 2004. The Open: Man and Animal. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Appadurai, Arjun. 2006. Fear of Small Numbers. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly Silver. 1984. ‘Labor Movements and Capital Mitigation: The US and Western Europe in World-Historical Perspective.’ In Charles Bergquist, ed., Labour in the Capitalist World-Economy, 183-216. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Barron, James and Colin Moynihan. 2011. ‘City Reopens After Park Protesters are Evicted,’ The New York Times, 15 November. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/16/nyregion/police-begin-clearing-zuccotti-park-of-protesters.html?mtrref=undefined&gwh

Baudrillard, Jean. 1975. The Mirror of Production. St Louis: Telos Press.

Berardi, Franco. 2009. Precarious Rhapsody. New York: Minor Compositions.

Benjamin, Walter. 1999. The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Beutler, Brian. 2016. ‘Conservatives Are Desperate to Pretend Donald Trump Never Happened,’ The New Republic, 8 August. https://newrepublic.com/article/135871/conservatives-desperate-pretend-donald-trump-never-happened.

Bey, Hakim. 1994. Immediatism. New York: Autonomedia.

Bradley, Pauline. 1997. 'Liverpool Dockers Dispute - Better than Prosac: Proof that the Personal IS Political,’ Asylum. http://www.asylumonline.net/sample-articles/liverpool-dockers-dispute-better-than-prosac-proof-that-the-personal-is-political/.

Castoriadis, Cornelius. 1997. The Imaginary Institution of Society. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Cohn, Nate and Toni Monkovic. 2016. ‘How Did Donald Trump Win Over So Many Obama Voters? The New York Times, 14 November. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/15/upshot/how-did-trump-win-over-so-many-obama-voters.html.

Conio, Andrew. 2015. Occupy: A People Yet To Come. New York: Open Humanities Press.

Cox, Daniel, Rachel Lienesch, and Robert P. Jones. 2017. ‘Beyond Economics: Fears of Cultural Displacement Pushed the White Working Class to Trump.’ Washington, DC: Public Religion Research Institute. https://www.prri.org/research/white-working-class-attitudes-economy-trade-immigration-election-donald-trump/.

Day, Richard J.F. 2005. Gramsci is Dead. London: Pluto.

DeLanda, Manuel. 2002. Abstract Science and Virtual Philosophy. New York: Zone Books.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. 1972. Anti-Oedipus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press (Translated by Brian Massumi, 1987).

Deleuze, Gilles. 1992. ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control,’ October, Winter 59.

Dubriwny, Tasha N. 2005. ‘Consciousness-Raising as Collective Rhetoric: The Articulation of Experience in the Redstockings' Abortion Speak-Out of 1969. Quarterly Journal of Speech 91, no. 4, 395-422.

Dyer-Witheford, Nick. 2005. ‘Cyber-Negri: General Intellect and Immaterial Labour,’ Pp. 136-62 in The Philosophy of Antonio Negri: Resistance in Practice, edited by Timothy S. Murphy & Abdul-Karim Mustapha. London: Pluto.

Edwards, Richard. 1979. Contested Terrain: The Transformation of the Workplace in the Twentieth Century. New York: Basic Books.

Ekman, Paul. 1980. ‘Facial Signs of Emotion Experience,’ Journal of Personal and Social Psychology 39, no. 6, 1125-1134.

Escobar, Arturo. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Faiola, Anthony. 2011. ‘London riots: Cameron vows ‘fightback’ amid public debate over police response,’ The Washington Post, 10 August. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/cameron-on-riots-we-will-not-put-up-with-this/2011/08/10/gIQA9z2O6I_story.html.

Faun, Feral 1999. Feral Revolution. http://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/feral-faun-essays.

Federici, Silvia. 2006. Precarious Labour: A Feminist Viewpoint. http://inthemiddleofthewhirlwind.wordpress.com/precarious-labor-a-feminist-viewpoint/.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Friedan, Betty. 1963. The Feminine Mystique. London: WW Norton and Co.

Gelderloos, Peter. 2015. The Failure of Non-Violence. New York: Left Bank Books.

Goldfield, Michael. 1987. The Decline of Organized Labour in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Guattari, Félix. 1984. Molecular Revolution. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Guattari, Félix. 1992. Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Gupta, Arun. 2015. ‘What Became of Occupy Wall Street?’ Counterpunch, 6 November. http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/11/06/what-became-of-occupy-wall-street/.

Hardt, Michel & Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Healy, Patrick and Maggie Haberman. 2016. ‘95,000 Words, Many of Them Ominous, From Donald Trump’s Tongue,’ The New York Times, 14 November. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/06/us/politics/95000-words-many-of-them-ominous-from-donald-trumps-tongue.html.

Heidegger, Martin. 1927. Being and Time. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Holloway, John. 2002. Change the World Without Taking Power. London: Pluto.

Holmes, Brian. 2004. The Spaces of a Cultural Question. http://www.republicart.net/disc/precariat/holmes-osten01_en.htm.

Institute for Precarious Consciousness, The. 2014. ‘Anxiety, affective struggle, and precarity consciousness-raising,’ Interface 6, no. 2, 271-300.

Invisible Committee, The. 2009. The Coming Insurrection. New York: Semiotext(e).

Invisible Committee, The. 2014. To Our Friends, New York: Semiotext(e).

Juris, Jeffrey S. 2008. ‘Performing Politics: Image, Embodiment, and Affective Solidarity during Anti-Corporate Globalization Protests,’ Ethnography 9, no. 1, 61-97.

Karatzogianni, Athina and Andrew Robinson. 2010. Power, Conflict and Resistance in the Contemporary World. London: Routledge.

Karatzogianni, Athina 2012, WikiLeaks Affects: Ideology, Conflict and the Revolutionary Virtual. Pp. 52-76 in Digital Cultures and the Politics of Emotion: Feelings, Affect and Technological Change, edited by Athina Karatzogianni and Adi Kuntsman. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Kazin, Michael. 2016. ‘The Fall and Rise of the U.S. Populist Left,’ Dissent Magazine, Fall. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-fall-and-rise-of-the-u-s-populist-left.

Kierkegaard, Soren. 1844. The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Oriented Deliberation in View of the Dogmatic Problem of Hereditary Sin, New York: Liveright Publishing.

Kingsmith, A.T. 2016. ‘Why so serious? Framing comedies of recognition and repertoires of tactical frivolity within social movements,’ Interface 8, no. 2, 286-310.

Knabb, Ken. 2006. Situationist International Anthology. New York: Bureau of Public Secrets.

Kroker, Arthur, Marilouise Kroker, David Cook. 1990. ’PANIC USA: Hypermodernism as America's Postmodernism.’ Social Problems 37, no. 4, 443-459.

Kushner, Jacob, 2016. ‘The Voluntourist’s Dilemma,’ The New York Times. 22 March. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/22/magazine/the-voluntourists-dilemma.html.

Kropotkin, Peter. 1896. The State: Its Historic Role. http://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-the-state-its-historic-role.

Lacan, Jacques. 2014. Anxiety: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. New York: Wiley.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. 1996. ‘Immaterial Labour.’ Pp. 132-46 in Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, edited by Paulo Virno and Michael Hardt. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Luxembourg, Rosa. 1906. The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Matin, Lundi. 2016. ‘Reflections on Violence,’ Anarchist News, 1 May. http://anarchistnews.org/content/reflections-violence.

Marx, Karl. 1939. Grundrisse: Introduction to the Critique of Political Economy, London: Penguin Books.

Marx, Karl. 1975. Early Writings. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Massumi, Brian. 2015. Politics of Affect. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

McCormick, Thomas J. 1989. American’s Half Century: United States Foreign Policy and the Cold War. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

McMarvill, Brian and Rob Ricos. ‘Empire and the End of History,’ Green Anarchist 67.

McGuire, Patrick. 2015. ‘Toronto Police Chief Bragged About Monitoring Protesters and Anonymous Is Pissed,’ Vice Magazine, 19 March. https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/watch-torontos-police-chief-brag-about-spying-on-political-protesters-263.

Minton, Anna. 2012. ‘CCTV increases people's sense of anxiety,’ The Guardian, 30 October. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/oct/30/cctv-increases-peoples-sense-anxiety.

Moody, Kim. 1988. An Injury to All: The Decline of American Unionism. London: Verso.

Negri, Antonio. 1999. Insurgencies: Constituent Power and the Modern State. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Negri, Antonio. 2013. The Winter is Over: Writings on Transformation Denied, 1989-1995. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

New York Times Editorial Board, The. 2016. ‘Donald Trump’s Scary Election Day Gambit,’ The New York Times, 12 October. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/13/opinion/donald-trumps-scary-election-day-gambit.html?_r=0.

Perez, Rolando 1990. On An(Archy) and Schizoanalysis. New York: Autonomedia.

Peterson, Abby 2001. Contemporary Political Protest: Essays on Political Militancy, Aldershot: Ashgate.

Prins, Nomi. 2016a. ‘Donald Trump’s Anti-Establishment Scam,’ Truth Dig, 11 July. http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/donald_trumps_anti-establishment_scam_20160711.

Prins, Nomi. 2016b. ‘Trump Wins (Even If He Loses),’ Tom’s Dispatch, 10 July. http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/176162/.

Pomerantsev, Peter. 2016. ‘Why We’re Post-Fact,’ Granta, 20 July 2016. https://granta.com/why-were-post-fact/.

Radosh, Ronald. 1969. American Labour and United States Foreign Policy. New York: Random House.

Reger, Jo. 2004. ‘Organizational ‘Emotion Work’ Through Consciousness-Raising: An Analysis of a Feminist Organization.’ Qualitative Sociology 27, no. 2, 205-22.

Reich, Wilhelm. 1980. Character Analysis. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Robinson, Andrew and Simon Tormey. 2008. “Is ‘Another World’ Possible? Laclau, Mouffe and Social Movements,” in The Politics of Radical Democracy, eds. Adrian Little and Moya Lloyd. Edinburgh: Edinbugh University Press.

Robinson, Andrew and Simon Tormey. 2009. “Utopias Without Transcendence? Post-Left Anarchy, Immediacy and Utopian Energy,” in Globalization and Utopia: Critical Essays, eds. Patrick Hayden and Chamsy el-Ojeili. London: Palgrave.

Robinson, Andrew. 2010. “Symptoms of a New Politics: Networks, Minoritarianism and the Social Symptom in Žižek, Deleuze and Guattari,” Deleuze Studies Vol. 4. No. 2, 206–233.

Ross Arthur M. and Paul T. Hartman. 1960. Changing Patterns of Industrial Conflict. New York: Wiley.

Rupert, Mark. 1995. Producing Hegemony: The Politics of Mass Production and American Global Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sartre. Jean-Paul. 1943. Being and Nothingness. New York: Routledge.

Shreve, Anita. 1989. Women Together, Women Alone. New York: Ballantine.

Sorel, Georges. 1915. Reflections on Violence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Press.

Spinoza, Benedict de. 1677. Ethics, Penguin Classics.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1999. Critique of Postcolonial Reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tompkins, Silvan. 1995. Exploring Affect: The Selected Writings of Silvan S. Tompkins. Ed. Virginia E. Demos. New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Ulmer, Gregory L. 2005. Electronic Monuments. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Vaneigem, Raoul. 1967. The Revolution Of Everyday Life. New York: Rebel Press.

Virilio, Paul. 1977. Speed and Politics: An Essay on Dromology. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Virno, Paolo. 2004. The Grammar of the Multitude. New York: Semiotext(e).

Waldman, Paul. 2016. ‘If you voted for Trump because he’s ‘anti-establishment,’ guess what: You got conned,’ The Washington Post, 11 November. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/plum-line/wp/2016/11/11/if-you-voted-for-trump-because-hes-anti-establishment-guess-what-you-got-conned/?utm_term=.7ef5d3dfe30e.

Weber, Beat 2004. Everyday Crisis in the Empire. http://republicart.net/disc/precariat/weber01_en.htm.

Weissmann, Shoshanna. 2013. ‘Obama For America to Continue Administration Trend Of Corporate Cronyism,’ Policy Mic, 26 April. https://mic.com/articles/34795/obama-for-america-to-continue-administration-trend-of-corporate-cronyism#.7W5iqiBjw.

Xaykaothao, Doulay. 2015. ‘Black Lives Matter demonstrators dig in at Mpls. police precinct, undeterred by rain, cold,’ MPR News, 17 November. http://www.mprnews.org/story/2015/11/17/black-lives-matter-occupies-4th-precinct.

Žižek, Slavoj. 1999. The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology. London: Verso.

Notes

- As opposed to the intersubjective and interdisciplinary, the notion of extrasubjective and extradiciplinary will be deployed here. When exploring the political potentials of affect the concept of extrasubjectivity seems more useful because individualistic subjectivity—and the intersubjective relation between individualistic subjectivities—is bypassed insofar as the social and affect are directly linked to one another in the production of social states of affairs. As a result, responsibly is attributed to a more affective collective responsibility, thereby surpassing our need to deal in/with the liberal notion of individual responsibility.

- See, for example: Weissmann (2013); New York Times (2016); Beutler (2016).

- See, for example: Cohn and Monkovic (2016).

- A political spectrum which insists on enforcing various ideological distinctions between the left and the right has become somewhat out-dated on a spectacular political terrain in which both liberal and conservative parties are more concerned with furthering processes of financialisation abroad and expanding the reach of neoliberalism at home. Thus the distinction made here, while largely illusory—especially in the case of partisan politics within liberal democratic states—is justified because signifiers of left and right are familiar terms that allow this essay to cover more conceptual ground that would otherwise be possible.

- See, for example: Peterson, 2001; Juris, 2008; Karatzogianni, 2012.

- The distinction between feelings and emotions was highlighted by an experiment conducted by Paul Ekman (1980) who videotaped American and Japanese subjects as they watched films depicting facial surgery. When they watched alone, both groups displayed similar expressions. However, when they watched in groups, the expressions were different. Thus we broadcast emotion to the world—sometimes that broadcast is an expression of our internal state other times it is contrived to fulfill social expectations.

- The concept of affect is transversal. Prime among these are the categories of the subjective and the objective. Although affect is all about intensities of feeling, the feeling process cannot be characterised as exclusively subjective or objective—nor can they be wholly individualistic or collective. For this reason Deleuze (1992) develops the concept of the dividual (or dividuality), which functions as a physically embodied subject that is endlessly divisible via the modern technologies of control, like computer-based systems.

- See, for example: Escobar, (1995: 133-4); Berardi, (2009: 43).

- See, for example: Baudrillard, (1975: 58); Guattari, (1984: 89-90); Pere (1990: 24-9).

- As Pomerantsev (2016) points out, this equalling out of truth, shame, fact, and falsehood is both informed by and takes advantage of the all-permeating relativism of late capitalism thought, which has trickled down over the past thirty years from academia to the media and then everywhere else. This school of thought has taken up the maxim by someone like Trump: ‘there are no facts, only interpretations,’ to mean that every version of events is just another narrative, where lies can be excused as ‘an alternative point of view’ or ‘an opinion’, because ‘it’s all relative’ and ‘everyone has their own truth.’

- This three-pronged transition is somewhat of an oversimplification of course, but one that is, I think, justified by the overall point that I am trying to make. The idea that ‘no one is bored’ today is a simple over-generalization. Surely there are people experiencing terminal boredom just as they are terminal anxiety—likewise, those who are bored are subjected to the same anxious compositions as those whose suffer anxiety surely experience boredom. When using the term dominant affect, this is not to say that this is the only reactive affect in operation. The new dominant affect can relate dynamically with other affects. For example, a call-centre worker (in the Global North or South) is bored and miserably paid, but importantly, it is anxiety that keeps her/him in this condition, preventing the use of old strategies such as unionization, sabotage and dropping out.

- Also known as a sanctioned ignorance in Spivak (1999), a social symptom in Žižek (1999: 138-40), and a culture of silence or submersion in Freire (1970).

- See, for example: Guattari (1992); Lazzarato (1996).