Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 38 (2022)

Fallen: Generation, Postlapsarian Verticality + the Black Chthonic

Cecilio M. Cooper

University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Abstract: Man’s fall from Edenic grace as well as Satan’s mirrored expulsion from heaven shapes Judeo-Christian territorialization of vertically oriented space in the Atlantic World. Subterranean registers underlie ecological layers stretching up from the globe’s immediate terraqueous surface to celestial extremes above. Engaging afropessimist and demonological analytics, this article probes how underground space is territorialized as a diabolical province. Moreover, it assesses how subsurface realms are portrayed as racialized components of a celestial-terrestrial-aquatic territorial amalgam. Signaling geographic location and cosmological import, the occulted chthonic realm below is an infernal site between Earth’s crust and core. By examining how verticality inflects blackness’ circulation throughout alchemy, scripture, property law, demonology, and ecocriticism, I show how it serves as a fulcrum for postlapsarian territorialities.

While adherents of all three Abrahamic faiths (i.e. Judaism, Islam, and Christianity) have instrumentalized enslaved African-derived persons to stoke their conquests, the Eurocentric traditions of the Christian denominations among them seem to have most inspired the architects of settler-colonial governance in the New World. They not only championed their petitions for unshared rule as licit, but also sacredly sanctioned by the concentrated sovereign power of a single peerless deity. In order to proffer a cosmological account of Atlantic World territorialization, we must examine how theological doctrine undergirds renderings of territory as a convergence of epistemological, ontological, economic, and ecological exigencies. By assessing how cosmology inflects cosmography, I show how blackness is intrinsic to colonial world-making and world-breaking enterprises. Cosmology encapsulates comprehensive explanations of the universe’s structure and maturation. Cosmography describes codified attempts to graphically map the known world and beyond. While my larger project engages land law and property law as instruments of territory formation, it does not treat the (necro)politics of possession as reducible to their juridical domain. Political theology persists as a discursive field in which deliberations around cosmology, space, and authority seem most legible. Yet, this essay’s cardinal preoccupation with (anti)blackness is expressed through a decidedly demonological rather than purely theological mode of appraisal. A measured “reframing of political theology with or as political demonology [emphasis in original]” allows me to elucidate how blackness is inextricable from ideas around both the chthonic and the postlapsarian. Chthonic underworlds get cordoned off as blackened diabolical provinces in ways that impel the Fall of Man and buttress postlapsarian racial realities. What I term the black chthonic circulates symbolically as a subsurface incubator for counter-culture, hell, chaos, death, darkness, indeterminacy, decay, disorder, extraction, and much more. The following pages trace circulations of chthonic blackness throughout alchemy, scriptural exegesis, occult iconography, and ecocriticism, which are regimes of knowledge that often straddle science and magic.

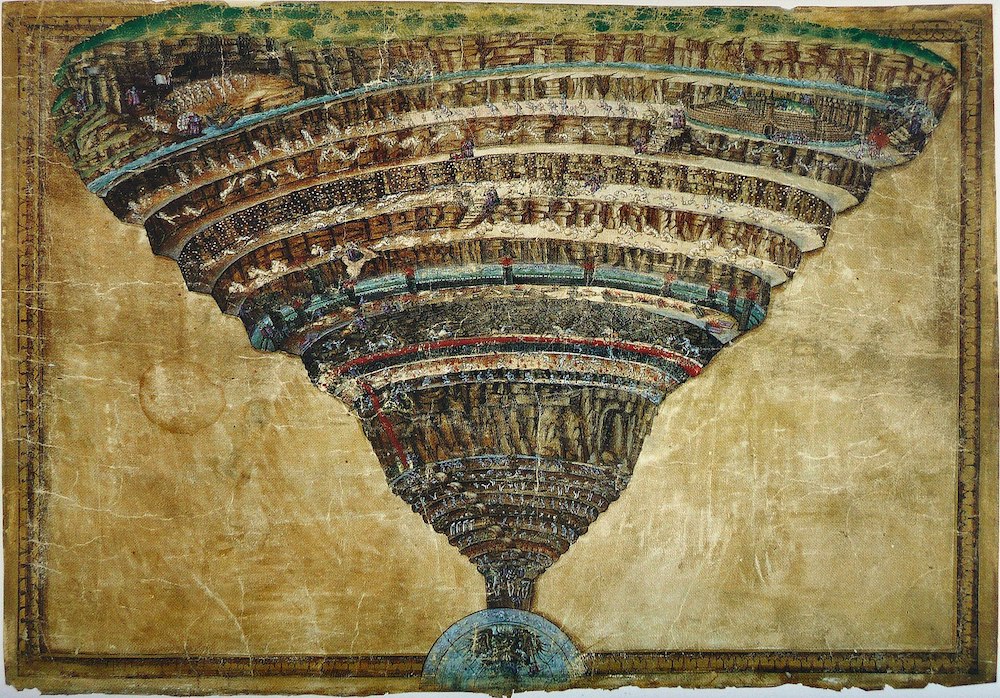

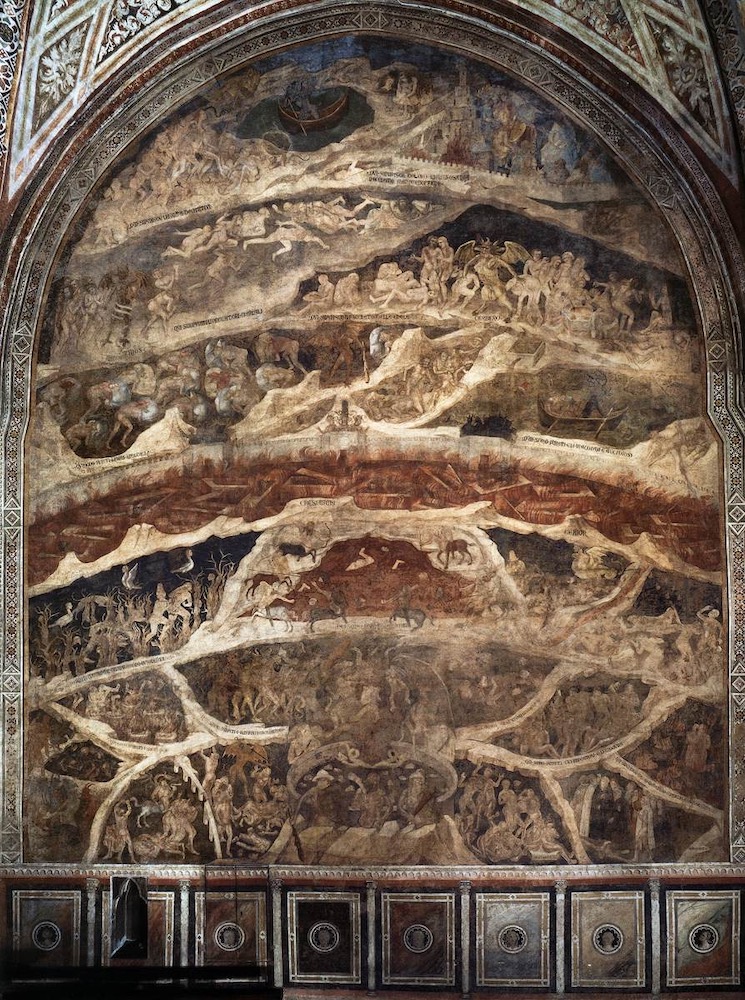

Subsurface realms are indeed racialized aspects of the celestial-terrestrial-aquatic amalgam that suffuses Atlantic World territory. Subterranean registers underlie ecological layers stretching up from the globe’s immediate terraqueous surface to celestial extremes far above. The territorialization of subterranean or subaquatic space is theologically inflected by Man’s fall from Edenic grace as well as Satan’s mirrored expulsion from heaven. When the cisgender-heterosexual dyad of Adam + Eve plummet from sacred lofts toward the sinful earthly plane, these prototypical humans draw nearer to abyssal hell below. What lies underground is widely reputed to be a habitat for supernatural entities, light-deprived extremophiles, and precious minerals. Signaling geographic location and cosmological import, the occulted chthonic realm is an infernal site between Earth’s crust and core. Monotheist Abrahamic faiths and polytheist Greco-Roman traditions alike attest that chthonian realms pulse with shadowy telluric energy. Water tables, mines, crypts, and roots are also among what populate earthly recesses beneath us.

Ultimately, I aim to excavate what disavowedly tethers blackness to chthonic concepts, organisms, and architecture in ways that fuel slavocratic settler-colonial pursuits. My foray into political demonology as a mode of critical black inquiry troubles much of black studies and political theology’s customary engagements with questions around the sex-gender binary, worldliness, and the profane. Political demonology emanates from the occult study of witch-hunting and supernatural evil, which represents unions between witches and demons as idealized orgiastic bestiality. Relatedly, “demonic grounds” are those chaotic places and positions beyond the policed thresholds of dominant symbolic systems. It is in this vein that I interrogate blackness as a fulcrum of Atlantic World racial schemas hinging pre- and postlapsarian territorialities to chthonic and abyssal fallenness. The following paragraphs begin to lay out the analytic scaffolding through which my ongoing considerations of darkness, chaos, and verticality alight.

Surface + Verticality |

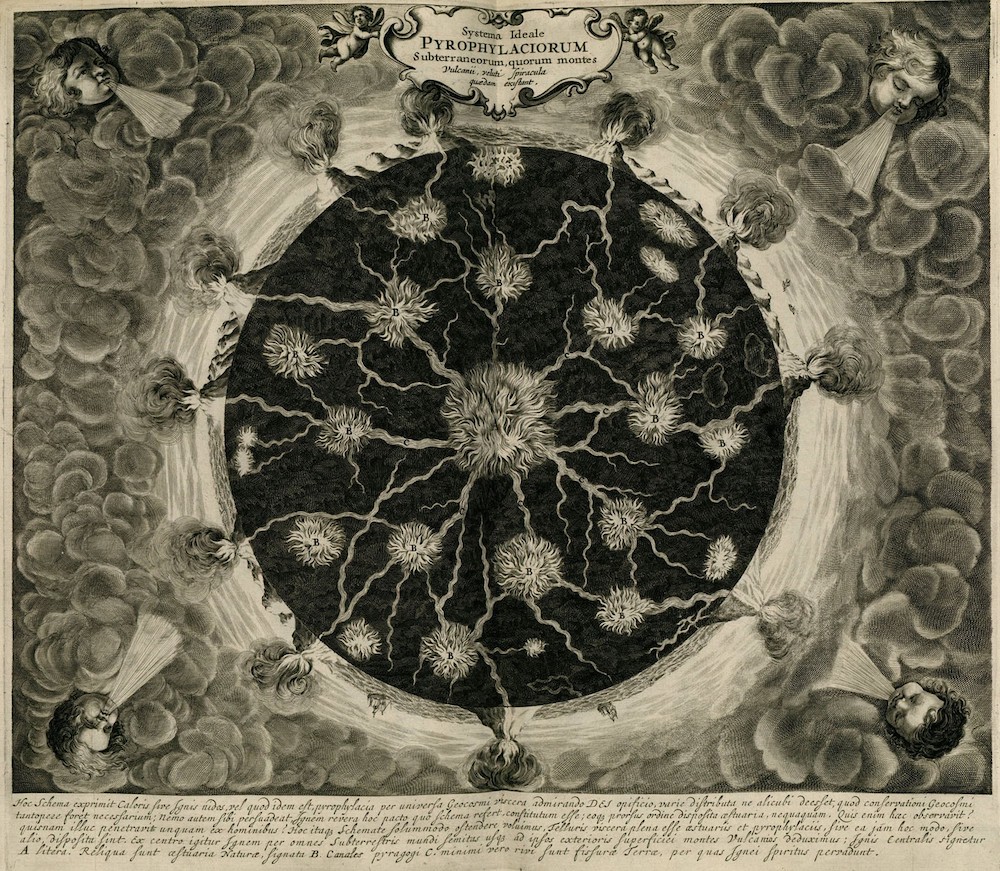

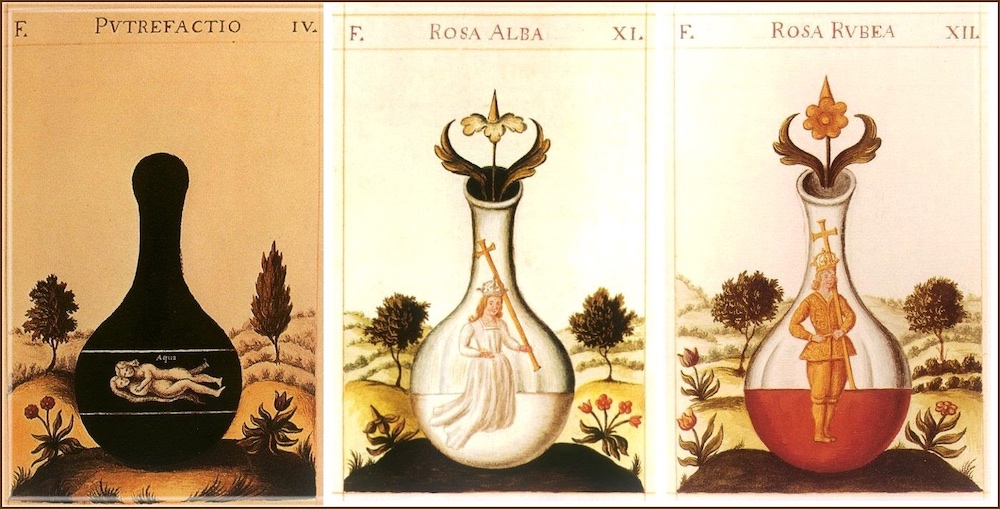

Subsurface, terraqueous, and celestial realms together comprise a worldmaking territorial order structured in accordance with monotheist doctrines. As we descend through territorial space toward the planet’s core, we confront increasingly debased positions within a vertically oriented hierarchy. Theocratic valorization of an omnipotent and omniscient Lord serves as the cosmographical basis for Atlantic World territorialization. Whether approaching space as a linear, planar, or multi-dimensional concept, cosmography aims to comprehensively map the ordered universe from the perspective of human observers. Cosmography traditionally embraces astronomy and cartography, which are disciplines dedicated to celestial and terrestrial space. Alchemy, anatomy, and demonology merit mention as offshoots of cosmographical study for several reasons: alchemy speculates that celestial forces transform metal mined underground into superior substances topside, anatomy charts and classifies bodily components in ways that complement cartographic grammars, and demonology probes how diabolical beings from the subsurface realm of hell influence terrestrial activity.

Aristotle promoted the idea that the universe was tiered such that the weightless Empyrean floated atop the heavier elements of earth, air, fire and water beneath. Ptolemaic perspectives positing geocentric and geostatic configurations of the cosmos also became thickly inscribed onto early modern cosmographic imaginaries. So the idea that a stationary Earth served as the focal point for other celestial bodies’ orbits made the planet also seem an echo of God’s cosmological centrality.

The celestial realm is the summit of territorial order because it is believed nearest the supreme deity’s vaulted throne. The terrestrial plane just beneath cushions Adam’s landing after his rectilinear fall from grace. These demonic grounds comprise a cosmological interval flanked by the superlunary and subterranean-subaquatic realms. Sin gestates and spreads across the globe, penetrating its exterior and befouling its substrates. Evil arises from the depths of hell below; this diabolical province countervails the lofty heavens.

I foreground the cosmological significance of surface and verticality because focusing solely on conflicts that erupt upon the face of the Earth as the spatial limit of colonial encounter amounts to confusing the flat cartographic map for the multidimensional expanse of the territory. My concern with the black chthonic diverges from tendencies to exclude subsurface phenomena when itemizing the contested veneers of territorial sites. The terrain of conquest is at once empirical and supernatural, hypogeal and extraterrestrial. Rather than allow legible surface activity to continually overshadow what transpires in submarine, underground, or empyrean spheres, I believe other territorial factors should be examined in concert. This essay gestures towards that end.

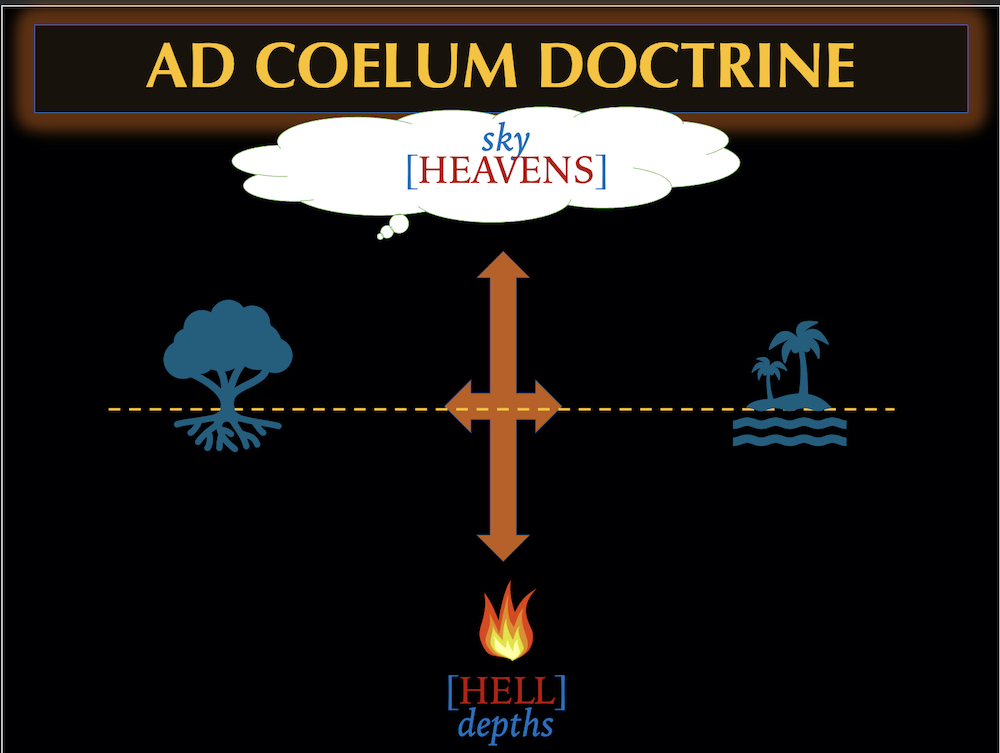

Ad Coelum Doctrine |

My approach to territory as a multidimensional possession draws from a principle of property law. The ad coelum maxim outlines how a parcel of land, the area overhead, and that directly underneath it together constitute a vertically oriented unit of territory perpendicular to the planet’s surface.

Encased by thick concentric layers of mantle and an outermost layer of life sustaining crust, the Earth’s iron rich core is the geological heart of chthonic space. The core serves as the embedded reference point through which property law and land ownership have been legally determined. Jurists typically translate the original maxim cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum from Latin to mean that a deed covers ownership of a column of space between the planet’s surface up to the sky above (coelum). Subsequent invocations of the maxim append et ad inferos so that the indefinite area in question not only extends up from topsoil to the atmosphere’s upper limit (coelum), but also down to the center of the Earth (inferos). In practice, cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et ad inferos would mean that “each landowner in the United States supposedly owns a slender column of rock, soil, and other matter stretching downward over 3900 miles from the surface to a theoretical point in the middle of the earth.” Antecedents to twenty first-century applications of the ad coelum doctrine (alternately termed the cujus est solum maxim) to international aviation, pollution, petroleum, water, and mineral rights have been traced to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English common law.

What I wish to highlight for the purposes of my argument here are the slippages between uses of geographic and geological locations (airspace and underground) for theological and demonological concepts (heaven and hell) within modernist jurisprudence. To me this reflects how legal, political, and economic understandings of territory are deeply infused with Judeo-Christian precepts. One is still likely to see coelum translated as “heaven” and inferos as “hell” alongside “sky” and “to the lowest depths,” respectively, when framed within the maxim’s context. For example, Oxford’s Guide to Latin in International Law directly states than an abbreviation of the maxim usque ad coelum (et ad inferos) means “All the way to heaven (and all the way to hell).” A symmetry is devised between heaven and hell that resonates with the congruity of the microcosm with the macrocosm. In rarer instances, the ad coelum maxim is shown as ending with et ad infernos rather than et ad inferos. Though inferos and infernos are nearly identical in spelling, the latter more accurately conveys “hell” in Latin than the former. Inferos describes lower places or statuses like ‘inferior’ would. However, infernos is “…comparable to the English “infernal,” an adjective meaning hellish. It inclines the reader to think of the flames and torments of hell.” Distinctions between hell as a harrowing existential condition and hell as a plottable physical location are conflated within legal scholarship on the ad coelum maxim. It is beyond the ambitions of this essay to conceptually trace just how the problem of netherworld geography became firmly affixed to property law. Yet, the ad coelum maxim warrants acknowledgement because it evinces the demonological underpinnings of territorial sovereignty.

Given that the parameters of the maxim are anchored by and oscillate the Earth’s molten outer core as a focal point, perhaps terming it the “ad inferos maxim” might be more apt shorthand than the “ad coelum maxim’s” emphasis on a firmamental roving target. An amorphous cloudless sky might appear static when viewed in short increments of time from naked eyes. However, celestial landmarks like constellations, moons, or other planets shift position because they and Earth simultaneously rotate and orbit along their own paths. At midday, the sun shines directly overhead appearing perpendicular to the ground. Yet by sunset, the sun recedes below the horizon due to the Earth’s constant spinning. In other words, “…what we customarily call the vertical is simply the horizontal at a particularly steep angle.” This is just one instance where verticality’s tendency to slope into and out of horizontality is discernible, thereby revealing the unstable rationale for a whole sector of property law. So, while this essay zeros in on verticality as a topical focus, it does not assume that verticality and horizontality are strictly bifurcated spatial orientations. The vertical and horizonal vectors of cosmographic grids may vary in magnitude and direction while sharing similar capacities for structuring sociopolitical power differentials.

Disscensus |

It is imperative that we accentuate (anti)blackness’ intimate relation to infernal territoriality in order to illuminate some misunderstood aspects of its cosmological and ontological registers. Even supposedly degodded scientific expositions on blackness and Black people tend to latently espouse ideas around natural causality and universalist objectivity. When not appraised from theocentric vantages, blackness then gets regarded as a cosmological integrant best understood via secular lenses competing for a similar degree of authority. Whiteness, a symbolic antidote to blackness’ inherent sinfulness or privation, is valorized as blackness’ superior obverse within this framework. Via the confluence of hermeneutics with empiricism, thinking along these lines conduces towards inhabiting and magnifying a supernaturally imbued epistemological gaze in ways that anticipate the panopticon. Subverting this orientation to questions around race and pre- and postlapsarian territoriality necessitates approaching certain research questions from demonological viewpoints. We can then more acutely pinpoint when the infinite possibilities imminent to black existence have been instead reduced to irredeemably damned villainous side characters or temporarily disgraced sinners still eligible for delayed salvation.

Going further, I argue that blackness, the fulcrum of Atlantic World racial schemas, structures the prelapsarian and postlapsarian territorialities that hinge to Abrahamic conventions to falling and fallenness. When Adam and Eve were evicted from paradise after archangel Lucifer and his allies were cast out of heaven, they plummeted toward the earthly plane along the same downward trajectory. God demoted Lucifer from his exalted stature for disrupting celestial consensus around the Almighty’s supremacy and His singular favor for humankind. Eve subsequently consuming fruit from the Tree of Knowledge also directly contravened God’s prohibition on partaking from it. Committing moral transgressions shapes how mortal, divine, and infernal beings are able to navigate the parameters of Judeo-Christian territoriality.

From a demonological standpoint, one might find that dissensus precipitates descent in the aforementioned biblical scenes. Here I marshal two inflections of ‘descent’ as I think about fallenness emerging both from Lucifer’s rebellion in Heaven and Eve’s defiance in Eden. Descent: 1) temporally, it describes lineages of ancestry; and 2) spatially, change from higher to lower positions. ‘Dissensus’ speaks to the juxtaposition of worldviews with, nonetheless, ranges of affinity between them. These worldviews are—to a degree—commensurable and mutually intelligible but one never becomes a replica of the other. Politics occurs in the dissensual gaps and intervals between them, in keeping with Jacques Rancière. Pushes toward consensus aim to police what is left unreconciled in these gaps and intervals until they are filled and worldviews converge under palls of political homogeneity. Descensus, a Latin word for descent, figures prominently in theological writing on Jesus Christ’s voyage to hell over the three days between his entombment and resurrection. Latin vocabulary used to sketch this event was later modified from descenus ad inferos (descent to the lowest depths) to descenus ad infernas (descent to hell) to bolster the idea that those already doomed to hell before Jesus Christ’s carnation could still be saved. Consequently, what was once understood as a neutral underworld for the dead (inferos) becomes conceptually indistinguishable from hell as the afterlife prison for sinners (infernas).

Disscensus is a portmanteau that I offer as a potentially expository merging of descent with dissensus. Disscensus speaks to blackness’ multifaceted cosmological function as a theological scandal hidden in plain sight. A thanatological kind of fallenness seems inherent to blackness in Judeo-Christian schema. Though Adam and Eve owe their existence to God as His first human creation, Satan too counts as their progenitor because he bequeathed his fallenness to them. As a spiritual contagion, fallenness was transmitted asexually to humankind (rather germinally or seminally) via Eve’s seduction. Generation after generation—from Eve to Ham onward—inherit sinfulness as part of Man’s earthly inheritance. The unfathomable depths to which blackness is destined is encumbered by an abyssal descensus. In medical terms, descensus has long been used to describe prolapsed organs. So, I use disscensus then to not only mean falling, but falling out of place. Blackness signifies dislocation. It inheres an anarchic potency and abysmal propulsion such that it is not strictly intelligible within the bounds of time and space. Blackness falls perpetually; it plummets without progressing. Its constant momentum is never punctuated by an arrival. Blackness encounters ground, but it does not stop there. The planetary surface is less a bulwark than an opaque and penetrable façade that blackness traverses en route to subterrestrial recesses and out again. Black fallenness is a cosmological impellent that is paradoxically incited by the intensity of blackness’ ontological stillness. Blackness is vestibular to culture, hovering at the threshold of the habitable world. David Marriott is among those who compelling explicates blackness’ intimacy with abysses and interminable descent via Fanonian readings of libidinal economy. Blackness is abyssal in manner of speaking because, as the extremes of particularity, it is simultaneously incarnated as the nadir of universality. Exemplified by descriptions of the abyss, I also accentuate how the downward motion that is constantly rehearsed in accounts of blackness betrays a cosmographical orientation that is volumetric, vertical, and demonological. What I term black disscensus aims to apprehend how cosmological dislocation and discord dictates how Black existence is demonologically emplotted within postlapsarian domain.

En Stigme Chronou |

Demonological discourse fomented a plethora of texts that trained readers on how to properly diagnose, classify, and manage evil phenomena that threatened to undermine Christian-dominated socio-political order. Reverend John Hale’s account of the Salem witch trials in A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft typifies this genre of writing. Hale was a Puritan pastor from the neighboring town of Beverly. He declares,

Satan sheweth to the Man Christ, all the Kingdoms of the World, and the Glory of them, in a moment of time (En stigme Chronou)…Now we know the World is round, and that a man can see but a small part of it at once. Therefore, that which Satan set before the eyes of Christ, was not all the Kingdoms of the World themselves, but an image and representation of them, and of their Glory, which Satan had framed…If then Satan can make an Image of the Kingdoms of the World, and of their glory which is the greater, then can he make the Image of a man, which is the lesser, and appear to man in such an image...

Hale terms the type of evil angel that arouses demoniacs to wickedness “...Daimon (which we Translate Devil) because they are full of wisdom, cunning, skill, subtilty and knowledge.” Daimon and its variant daemon first appear in Plato’s philosophy. In classical contexts, daimons were supernatural beings without legible agendas. The label referred “more generally to a kind of hidden or numinous force that shapes a person’s life” without clear-cut malevolent or benevolent intent.Daimon’s metamorphosis into demon hearkens to the good/evil moral dichotomy animating Judeo-Christian scripture. Alongside his daimon army, Satan is bestowed the zoomorphic cognomen “the Serpent” and his acolytes purportedly poison their victims in an ophidian fashion. He masterfully manipulates temporality and ocularity “in a moment of time (En stigme Chronou).” He flashes Jesus a composite of all the far-flung kingdoms of the world within a unified frame. Area once concealed beyond the horizon burst into singular view. What is striking about the particular example of devilment that Hale provides is the anxiety it exhibits about the capacity to visually represent the expanse of the world within one person’s field of vision. By allowing Christ in human form to access more knowledge than any human being should have capacity to fathom, Man is sinfully induced to elevating himself above God. Hale’s reference to en stigme chronou derives from the Gospel of Luke 4:5 and is “[p]erhaps the most definite expression of time found in the Bible.” The precise manner through which Christ has momentary access to an omniscient vantage point has been subject to interpretation. Did the Devil levitate Jesus so that he could survey the Earth below from a birds-eye view? Or rather, did the Devil project a panoramic vision into Jesus’ mind without needing to manipulate his body? Set in the wilderness, this portion of Luke’s New Testament Gospel narrates Jesus’ resistance to temptation. Satan’s magnificent display was meant to entice Jesus into requisitioning dominion over the earthly kingdom from his paternal God’s grasp.

Creatio ex nihilo: Gender + Generation |

Atlantic World cosmography spatially represents the planet’s nascence, design, and astronomic position in alignment with Abrahamic exegesis. Logocentric accounts of creatio ex nihilo posit that God spoke the ordered world into existence “out of nothing.” Alternate readings frame the nothingness of Genesis as less akin to complete absence than a limitless abyss. Prima materia is another name for the formless chaotic principle that served as creation’s tenebrous fundament.

Creatio ex profundis, defined as both “creation out of chaos” or “creation out of the watery depths (tehom),” supplants creatio ex nihilo throughout revisions in order to emphasize creation’s indeterminacy. In the former, spirit and matter are alchemically ushered into existence from a zone of nonbeing at the Creator’s behest. In the latter, primordial chaos is a preexistent unruly something also tamed through the commanding power of logos. This Greek term logos can connote the Word of God in earthly registers, unfleshed Knowledge, or secularized language-based systems of governance. Ex nihilo consists of an uncontrollable sea that ascends out of an inky abyss. Land congeals into a habitable world after it emerges beneath vast waters that contract into a smaller pool.

I am amenable to Catherine Keller’s finding that “demonization of the dark belongs to the foundational tehomophobia of Christian civilization.” The dark visual and literary codes used to caricature African-derived peoples were used almost interchangeably with those with which anthropomorphized renderings of demons were crafted. Not only was the “black-skinned demon of early Christian monastic literature…born from the association of blackness with sin and evil…, ” but blackness’ ignoble connotations have been directly attributed to God needing to rescue light from the dark abyss that ignited creation. Subsequently, hell too becomes shrouded in “darkness with regard to seeing God” because darkness signifies “the absence of grace.” Though Lucifer’s name means the “bringer of light,” he is paradoxically dubbed the “prince of darkness” because he is presumed the ultimate harbinger evil. Anti-darkness and antiblackness animate Abrahamic cosmography such that darkness, blackness, and the demonic coalesce via the ways time-space is mapped within its attendant cartography. Creatio ex profundis, “creation out of the watery depths,” is just as speculative a cosmogonic account as creatio ex nihilo, yet feels more explanatory because the former intimates how blackness’ dehiscence shapes Atlantic World territorialization.The dogmatic aggrandizement of creation from nothingness over creation from the chaotic abyss of the tehom is a high-stakes distinction with terrifically racialized implications. Debates around the substance of creation concentrate upon meanings of the Hebrew word compound tohu wa-bohu, appearing in Jeremiah 4:23 and Isaiah 34:11.

Tohu wa-bohu has been translated to mean “utter desolation,” “chaos primeval,” and “formless waste.” Tohu and bohu are barren areas situated above and below where heaven and earth should abide, respectively. When tohu and bohu conjoin into tohu wa-bohu, the distinct sites seem to function as a complex primordial substance alongside light, wind, water, earth, heaven, darkness, day and/or night. Both the Talmud and Old Testament describe the tohu and bohu as existing outside of the universe’s perimeter, abutting creation’s darkness. Tohu wa-bohu’s collision “…with darkness (and probably also tehom), were conceived of as the origins of evil.” Formlessness in the absence of light presented nearly too formidable an obstacle to the partitioning and maneuvering that instilling divine order demanded.

The esteemed account of creatio ex nihilo would seem to violate the law of conservation of matter, which holds that matter is neither created nor destroyed. The idea that matter can only change form is not only consistent with a creatio ex hyles (creation out of matter) hypothesis, but also becomes a cornerstone of the premier experimentation model called the Scientific Method. Scriptural interpretations of ex nihilic creation place chaos or nothingness as initially exempt from this process because there is no credible explanation for its existence at the onset of Genesis. Nihilo has an ontological gravitas that Jacques Lacan notably affirms as the basis of a primal lack. Nihilo can be acted upon by God and wrought into matter because it has supernatural immaterial properties stemming from its immemorial ontological status. In seventeenth-century Lutheran cosmology, a Germanic Protestant denomination, “the original creatio ex nihilo would be followed by a final reductio ad nihilum, a change from being to non-being.” Non-being to being onto non-being again. The end circles back to the beginning. The omega becomes the alpha and the alpha the omega. Rather than the embryonic fundament percolating in creatio ex profundis, darkness looms as creatio ex nihilo’s thanatological protagonist. It is a deathly counter to light, a menace to the desired messianic climax towards everlasting life. Black peoples—the darkest humans, nadirs of degeneration—were death manifest. They were/we are landmarks against which enlightened white Christians could gauge their degree of declension toward obliteration. The dark abyss is demonized and blackness indexes the diabolical. Black existence is marked by chattel status, quivering at the crossroads of moribundity-cum-vivacity. Blackness fluctuates through a swath of interstitial predicaments that appear as extremes. In the creatio ex nihilo origin story, chaos is matter’s fundament and makes the world’s genesis possible rather than serving as the antithetical seed of its undoing. Chaos has no agenda.

In this context, debates abounded as to where in the Mediterranean region (Israel, Rome, etc.) sat the center the of the universe. This omphalos was anthropomorphized cartographically on T-O mappae mundi as Christ’s navel.

If the world was territorially envisaged through the Savior’s splayed body, then partaking of the sacrament meant that Catholics surrendered their mortal coils as microcosms by ingesting morsels of his flesh. These lay people could become extensions of societas Christiana (the Christian kingdom) by welcoming the sacred world into their bodies. The chaotic pollutants that threatened to breach the empire’s walls not only embodied amorphous fluidity, darkness, and otherness, but also the concrete figure of the Antichrist. On this topic, Carl Schmitt notes, “…the Christian concept of the world…saw the empire as a restrainer (katechon) of the Antichrist.” Jesus’ satanic foe, “the Son of perdition” would induce the world-ending apocalypse without the “emergence of a universal eschatological emperor.” Black African and Amerindian peoples’ non-Christian/quasi-Christian/syncretic cosmologies were so disruptive they seemed aligned with the Antichrist’s challenge to the sovereign katechon.

Besides demonic grounds, Sylvia Wynter insightfully deems the planet’s “terrestrial realm” a “post-Adamic” landscape distinct from the “divine/celestial realms” where God rules from on high. The planetary surface becomes the confines where Man, the “fallen heir of Adam’s sin,” is forced to reside. Wynter astutely interrogates what implications “post-Adamic mankind’s enslavement to Original Sin” has for the mappings of astronomical and cartographic space. However, I want to pull Eve back into focus vis-à-vis Wynter’s commentary because it was her anti-authoritarian innovation that sparked the calamitous plot-twist in the Abrahamic family drama. Moreover, I view the fallenness that is commonly attributed to that Edenic scene as a dynamic that was actually initiated by Lucifer’s earlier uprising in heaven. So fallenness, as constitutive of the human, is not only a post-Adamic condition. Fallenness is post-Evic and post-Luciferian; resistance to naming it as such is a hallmark of cisheteropatriarchal political investments.

The Garden of Eden is cited as a flashpoint for gender-based suffering, as maintained by certain feminist outlooks. The spiritual discord chronicled therein would be experienced corporeally thereafter. Ever since Eve was fashioned from Adam’s rib, those assigned female at birth have been among those castigated as inferior variations of a pre-existing male exemplar. Whatever postlapsarian capacities Eve and her progeny would acquire to propagate organic life were facilitated by fleshly interactions between wombs, hormones, genitals, zygotes, and gonads. The ensemble of corporeal characteristics thought endemic to Eve’s ontology belongs to an apparatus that allows reproduction to occur via the fertilization of dimorphic sexual components. The uterus became fetishized as a reproductive locus of feminine dysfunction that would go on to be diagnosed in medical terms as hysteria. Uterine pains associated with menstruation and parturition were also judged fitting punishments for Eve’s impious offense. The Hermetic tradition revises Genesis and casts Adam, God’s first human creation, as an autogamous hermaphroditic figure rather than a cisgender man. In this version, Adam’s gender-extravagance enables him to procreate through self-fertilization. Sex-gender bifurcation, then, was a punitive consequence of the Fall instead of its pristine precursor. This suggests that the male-female dyad is an epiphenomenal condition of Man’s territorialization into the sublunary realm rather than a primeval mitosis that has been corrupted and in need of restoration. The gendered brutality that has been meted out for millennia to right the Fall’s imagined aftereffects is undeniably ubiquitous and devastating. Yet, I do not perceive the first couple’s inception from slimy clay, banishment from Eden, and breeding of cursed offspring as the period when holy procreative violence was inaugurated in the world. Instead, they seem to me belated incidents only made possible by a prior moment when blackness was a maligned albeit essential vehicle for cosmic conception. The contours of the sex-gender binary as we know it only crystallize against a pre-existing primal and incorporeal backdrop of blackness as asexual and chaotic (re)production manifest.

Cosmologically (and temporally) speaking, darkness is always-already because there is no facet of awareness when and where it has not existed. Blackness is therefore bereft of antecedents. Anteriority is foreclosed to blackness because blackness occasions the numinous grounds upon or empty set through which Abrahamic time-space is beheld. The incipient instance of distinction in the universe was the sequestering of light away from preternatural dark, according to scripture. So, blackness as darkness’ quintessence is the ante-binaristic milieu from which all subsequent modes of differentiation—sexual or otherwise—are accomplished. The violence that ensues from classifying life into genres—which is again to say genders—must first disembark from blackness as the launchpad for viability in the universe.

Understanding blackness as integral to material transmutation, Denise Ferreira Da Silva relatedly engages blackness as matter or “content without form, or materia prima.” Some slippages seem to occur in her theorizations of chaos’ relationship to matter that I would like to address. My research finds that the alchemical term materia prima (or prima materia) is not synonymous to consummate matter. Evidenced by blackness’ station at the magnum opus’ inception and the material anarrangement that occurs during this blackening stage nigredo, prima materia is actually the formless chaotic principle from which matter burgeons into an array of forms. Materia prima—blackness unharnessed—precipitates matter, so is not yet matter itself. Matter accomplishes itself via blackness. It is the chaos that lends materiality coherence and makes matter possible, rather than serving as its unadulterated equivalent. Recall my earlier discussion of Genesis, which recounts the universe’s indeterminant origins via creatio ex nihilo. Alchemically speaking, chaos is the original substance of creation or the prima materia used in the alchemical transmutation process to fashion gold. Prima materia stimulates a substance’s change from an integrated Adamic state to a disaggregated rawness that can then be perfected into matter proper. Da Silva provocatively concludes the essay “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞/∞” with “…blackness as matter signals ∞, another world: namely, that which exists without time and out of space, in the plenum.” The plenum refers to the entirety of space filled with matter as opposed to a vacuum, which is theoretically vacant of any material contents. For me, blackness’ demonological otherworldliness stems from its infinite territorializing (in)capacities. Blackness can become anything or nothing or even forego becoming altogether. Given its cosmological singularity, blackness need not inevitably crescendo into being good, agential, or useful.

What’s at stake is this: understanding blackness as chaos—as the entropic potential to homogenize systems to energetic morbundity or as anarchic jeopardy—lends itself to an unscripted and, perhaps, yet unthinkable set of socio-political outcomes. Construing prima materia as ante-matter or proto-matter or quasi-matter dislodges the seeming isomorphic relationship between blackness and matter as well as the political claims premised thereupon. If blackness is zero, zero is nothing, and nothing (ex nihilo?) is the other side of chaos, then blackness as chaos is that which can exist in any time and space rather than no time and space. Blackness has been violently overpacked with meaning too dense for a single signifier or terminus to hold. Matter ≠ blackness ≃ chaos ≃ quaquaversality.

Through a series of moves over two essays, da Silva enjoins us to consider blackness’ philosophical multivalence. She surmises that Black women correlate to the “female flesh ungendered” that operates as the zero degree of signification such that Black female = flesh = zero = materia prima = matter. This reading departs from Eurocentric alchemical cosmologies that postulate (a white cis-male or epicene) Adam as matter’s paragon. Again, zero is the absence of quantity, the least degree, and the threshold of positive and negative value. I interpret the nullity suggested by “zero degree of signification” not solely as emptiness, but also as supernumerary vacillation endowed with sex-gender capacities irreducible to the feminine. Rather than a fatalistic one-to-one correlation between blackness and femininity, I instead recognize blackness as sexuated entropy. We collectively struggle to make sense of this ontological exorbitance. Blackness spirals out in too many directions to be definitively domesticated— in other words, territorialized—as mere matter orbiting one sex-gender structural position. Matter is among blackness’ potential incarnations rather than its only predestination. Blackness is the agender chaotic fullness that precipitates femaleness, maleness, epicene, and any other prospective sex-gender particularity. Blackness is an inimitable cosmological medium for sexuated (re)generation itself.

Nigrum, Nigro Nigrius |

Constitutions of matter are underlying concerns of studies pertaining to psycho-sexual dynamics of kinship. Space in the essay does not permit me to discuss in great detail how Carl Jung takes up transformations of the psyche and soul in color-coded alchemical terms. But I’ll briefly share here that Jacques Lacan’s reading of the void in creatio ex nihilo is also relevant for understanding how creations of matter and knowledge inflect territorial apportionment. A vessel that gives shape to a void not only announces the void’s presence, but its potential effacement, according to his thinking. In other words, filling the hypothetical vase (that he uses as an example) would diminish its emptiness. Creationist mythologies can distort the fact that the vase’s emptiness becomes perceptible through the concave space of the hardened clay. Nothingness, nihil, is only made legible by the disavowed material that encases it. If matter is created from nothing (creatio ex nihilo), it too gives form to nothingness.The primordial abyss substantiates nothingness such that the matter created from nothing paradoxically inherits its eternal character.God, the unmoving mover, is defined by omnipotent vision and immortality. The undying powers of matter—captured by the law of conservation of matter that holds it to be neither created nor destroyed—can be perceived as rivaling that of the supreme progenitor. While aspiring to please and obey God is a secure path to piety, Judeo-Christian theology conversely insists that manipulating the material world in ways that mimic His prowess is a flagrantly demonic undertaking.

A resurgence in certain intellectual discussions of blackness and blackening processes can be attributed Jung’s excavation of early modern alchemy as a model for twentieth century psychological transformation. Sources explicitly covering nigredo, the blackening stage of the alchemical magnum opus, tend to mention the Swiss psychiatrist praised as founder of analytical psychology. Jung’s postulation of the collective unconscious as a universal expression of biological predispositions figures in Frantz Fanon’s account of colonial libidinal economies. Jungian psychology would like to suggest that a Black individual’s engagement with the collective unconscious has an injective relationship to that of a white person thereby dispensing with race as a determinant. The “vertical integration of anti-Blackness” is camouflaged psychoanalytically as ethical laterality innate to a humanist commons. Fanon shows how Europeans—from Jung to Freud and otherwise—are wedded to the idea of a “darkness inherent in every ego, of the uncivilized savage, the Negro who slumbers in every white man.” Blackness in Negro form serves as the archetypal figure in Jungian psychology. Racial blackness functions as a vector for collective catharsis, which Jung alleges is a biologically driven and universally inherited human condition.

Jung encourages alchemically minded psychiatrists to deploy “nigrum, nigro nigrius” as a way of framing Man’s psychological development in versicolored terms. This phrase’s Latin-to-English translations include, “blacker than the blackest black” and “black, blacker than black itself.” Nigredo instigates the color-coded cycle of transformation that defines alchemy’s magnum opus. It is followed by albedo’s purifying whiteness, citrinitas’ enlightening yellowness, and culminates with rubedo’s bloody redness. Alchemy’s quadripartite chromatic schema would come to resonate with Carl Linnaeus’ territorialized racial taxonomy, which divides the human species into varieties emerging from the continents of Africa, America, Asia, and Europe. The blackening stage of nigredo marks a period of devitalization and decomposition that matter must pass through before eventually achieving more idealized states. Steeped in darkness, stone or metal breaks down into essential components that together comprise prima materia. Cold, moist, and receptive female “seeds” percolate prima materia alongside their hot, dry, and active male counterparts. Judeo-Christian origin accounts of creatio ex nihilo heavily inflect alchemical interpretations of prima materia as an insubstantial cosmological starter. Consequently, alchemists imagined the first mortal Adam as prima materia’s sentient analogue. Man’s Fall from grace, then, was a religious expression of nigredo. This ailment manifested in physiological and psychological terms as melancholia, which was a humoral condition marked by profound sadness that was provoked by excessive amounts of black bile.

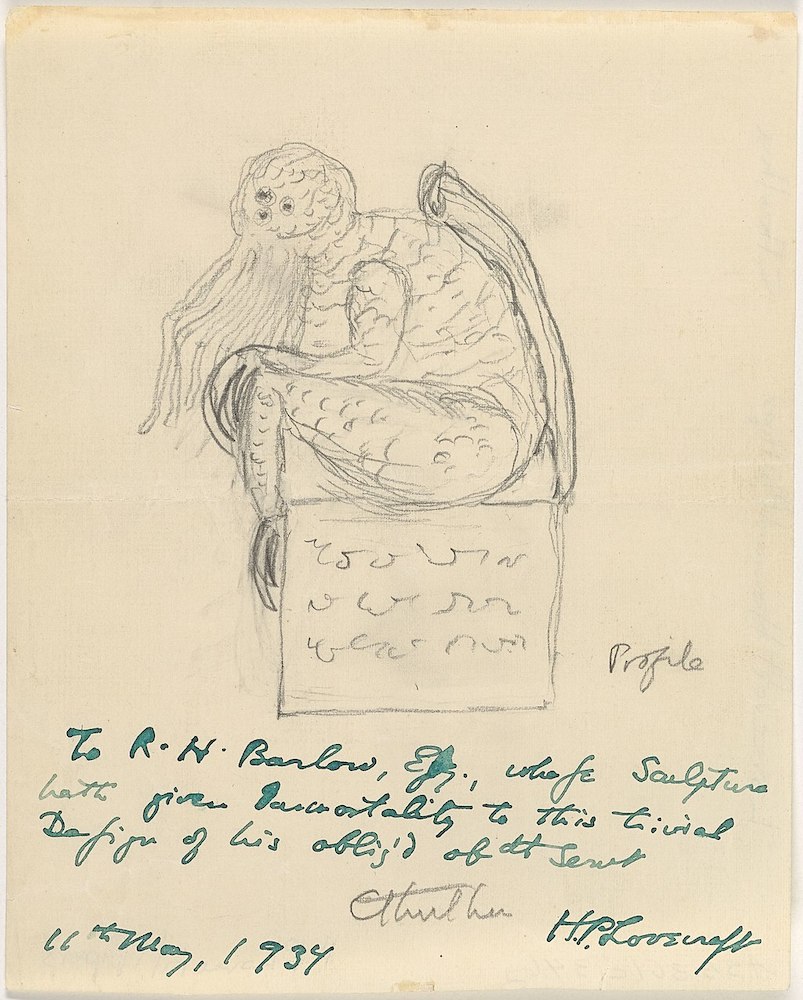

Nigrum, nigro nigrius approximates conditions found in sites impenetrable to light like the planet’s subterranean depths. It mirrors “the darkness of the earth’s core.” Blackness erupts onto the surface embodied as the “…‘dragon,’ the chthonic spirit, the ‘devil’ or, as the alchemist called it, the ‘blackness,’ the nigredo, and this encounter produces suffering…”[my emphasis]. While indispensable to the magnum opus’ elevated goals, chthonic nigrum nigrius nigro is still shunned like other wretched anathema slated for destruction when not racially fetishized. In its original Greek form, chthonios encompassed both subaquatic and subterranean space. The chthonic has since been more closely associated with deep strata, approaching the territorial nadir and planetary bowels, in counter-position to the aerial space of the territorial apex. Cthulhu is the grotesque bottom-dwelling entity with whom the adjectival word chthonic is fettered.

Donna Haraway’s vision of a redemptive Chthulucene in Staying with the Trouble intentionally shies away from interpretations of the chthonic associated with American horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. However, showrunner Misha Green’s sci-fi period series Lovecraft Country speculatively amplifies the racial sinews of Lovecraft’s literary oeuvre. The one-season drama debuted in 2020 and is based on Matt Ruff’s occult fantasy novel by the same name. Characterized as a “xenophobic recluse,” Lovecraft’s generative Cthulhu mythos saga envisages a “pantheon of hideous interstellar–extraterrestrial–interdimensional deities.”

He is celebrated for envelope-pushing novels and short stories, but also unleashed brazenly derogatory pieces like the poem “On the Creation of Niggers” into popular culture. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror illustrates the limits of life through abysmally dark amorphous creatures called Shoggoths. Eugene Thacker explains, “In Lovecraft’s prose, the Shoggoths are the alterity of alterity, the species-of-no-species, the biological empty set. When they are discovered to still be alive, they are described sometimes as formless, black ooze...”[my emphasis]. Haraway’s pronouncement to steer clear of both Lovecraft’s and occult luminary Aleister Crowley’s association of the chthonic with the aberrational or baleful is instructive. What she avoids is what should be interrogated.

Haraway rebrands ‘chthonic ones’ as tentacular monsters emanating from the underworld. Unconstrained, they no longer belong exclusively to Greek traditions. Chthonic ones use their agile appendages to create non-hierarchical multi-species networks that wind through all realms of the biosphere. The chthonic tentacles of her scheme seem, at first blush, similar to the decentralized branches of Deleuzo-Guattarian rhizomes despite no mention of them in this particular monograph. Like the rhizomatic, her chthonic vista eschews genealogy. She endorses sympoeisis as an alternative to autopoiesis arguing that the former lends itself to a collaborative multiplicity rather than self-generated individuation. A distinguishing feature of Haraway’s use of the chthonic is an ethical commitment to humanity’s sustainable coexistence with the rest of the planet. Deleuzo-Guattarian perspectives, exemplifying what Tiffany Lethabo King describes as “White nonrepresentational theory,” try to destabilize subjectivity in ways inclined to inhibit identifying white demographics as loci of settler violence. The sociopolitical consequences of their seemingly agnostic analysis are often deemed ancillary to the philosophical flair of their provocations. In Haraway’s slightly more politically driven study, kinship networks can be rewoven despite the influence of patriarchal genealogies on their blueprints. She envisions a world where chthonic ones commiserate freely with Hopi, Navajo, and Inupiat peoples. Haraway explains, “…chthonic ones are those indigenous to the earth in myriad languages and stories; and decolonial indigenous peoples and projects are central to my stories of alliance.” My concern with Haraway’s feminist corrective is that it requires expunging blackness from its framework. Her politically anti-Lovecraft posture masks the antiblackness of her allegedly pro-indigenous speculative future.

In the wake of chattel slavery, the chthonic cannot be divorced from the blackness that subsurface arenas have ecologically and cosmologically come to signify. Haraway’s hasty move to recuperate the chthonic by severing its Eurocentric ties to the Eldritch terrors that Lovecraftian interpretations readily betray seems motivated by a desire to disavow the antiblackness at the heart of the concept’s circulation. Lovecraft is racist without question, but the pejorative regard for blackness in his catalogue isn’t too far removed from the racial implications of Judeo-Christian exegesis or a host of other things, including white feminist ecocriticism. By dispensing with the (anti)black tenors of the chthonic, Haraway hopes to convince us that the Anthropocene is untenable while still disavowing how the ineluctable antiblackness of its framing has already infected the Chthulucene that is poised to replace it. Even in sprinkling in the collectively coined neologism ‘Plantationocene’ throughout Staying with the Trouble, it is unclear how the unchecked vestiges of chattel slavery will be attended to by a Chthulucene ethos indifferent to contending with how antiblackness occasions the epoch’s commencement. Her claims demonstrate an unwillingness to think both Native genocide and Black annihilation as constitutive bedrocks of certain phenomena mischaracterized as the Anthropocene. This book’s thesis exemplifies what Axelle Karera assesses as the erasure of racial antagonisms in Anthropocenean discourses. Haraway attending myopically to bipartite dynamics in a Chthulucene future portends nothing auspicious for the Black people who might manage to survive until its arrival. This symptomatic move replicates the absenting of a Black third perspective, which constricted the debates around settler-native intermingling that commemorated the Columbian quincentenary. Given that the chthonic is indelibly imbued with blackness, what does it say about the promise of white feminist visions for a “habitable, flourishing world” when they are still premised upon Black erasure/annihilation?

Conclusion |

It is prudent here to bring in Calvin Warren’s definition of antiblackness as “an accretion of practices, knowledge systems, and institutions designed to impose nothing onto blackness and the unending domination/eradication of black presence as nothing incarnated. Put differently, antiblackness is anti-nothing [my emphasis].” As limned earlier in this essay, abyssal darkness inspires awe as creatio ex nihilo’s unprecedented and volatile exponent of nothingness and chaos combined. Wrestling with the cosmological valences of blackness obliges us to refute wholesale positivist reclamations of blackness as holiness. This reactionary over-correction obscures and squanders the insurrectionary potential of embracing blackness’ cosmological alignment with the fallen, infernal, and subterrestrial. Blanket charges of Black sinfulness have been paradigmatically misattributed to Black misdeeds when this condition could more scrupulously be construed as an outgrowth of the “general dishonor” that is intrinsic to (Black) social death. Coincidentally, indictments of supposed demonic interference don’t all stem from pre-existing deviance or wayward depravity. The diabolical instead indexes entropic cataclysmic elements that endanger holy dominion. The antiblack order that currently envelopes us persists as a hindrance for Black wellbeing, so I propose that we regard anything able to throw it into flux—like the demonological—as an untapped resource for its revelatory overthrow. Inaccurate understandings of antiblackness’ scope will endure should we neglect to investigate territorialization’s cosmological role in antiblackness’ proliferation. Towards theorizing what I term the black chthonic and black disscensus, I’ve endeavored to show how Atlantic World territory—spanning celestial coelum to diabolical inferos—can be better ascertained through demonological and afropessimist analytics. Together they help me ascertain how dark diabolical forces are portrayed as compromising matter’s integrity, perverting normative kinship, dissolving sex-gender coherence, and disrupting space-time continuums. This essay addressed issues ranging from early modern alchemy to Judeo-Christian exegesis to property law to cosmic horror in order to further demystify the racialized facets of territoriality. Postlapsarian worldmaking is indeed vertically oriented and inflected by an antiblack symbology; it is one that incessantly ensnares Black diasporic peoples within annihilative predicaments. But, it does not have to stay this way forever. Leaning into the demonic could hasten its disintegration in ways we have yet to risk ideating.

Works Cited

Abraham, Lyndy. A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Abramovitch, Yehuda. “The Maxim Cujus Est Solum Ejus Usque Ad Coelum as Applied in Aviation.” McGill Law Journal, vol. 8, 1961, pp. 247-269.

de Armas, Frederick A. “The King’s Son and the Golden Dew: Alchemy in Calderón’s La Vida Es Sueño,” Hispanic Review, vol. 60, no. 3, 1992, pp. 301-319.

Banner, Stuart. Who Owns the Sky? The Struggle to Control Airspace from the Wright Brothers on. Harvard University Press, 2009.

Beattie, Tina. Theology After Postmodernity: Divining the Void—A Lacanian Reading of Thomas Aquinas. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Bradbrook, Adrian J. “Relevance of the Cujus Est Solum Doctrine to the Surface Landowner’s Claims to Natural Resources Located Above and Beneath the Land,” Adelaide Law Review, vol. 11, no. 4, 1988, pp. 462-483.

Brakke, David. “Ethiopian Demons: Male Sexuality, the Black-Skinned Other, and the Monastic Self.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 10, no. 3/4, 2001, pp. 501-535.

Byron, Gay L. Symbolic Blackness & Ethnic Difference in Early Christian Literature. Routledge, 2002.

Clark, Stuart. Vanities of the Eye: Vision in Early Modern European Culture. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Connell, Martin F. “Descensus Christi ad Inferos: Christ’s Descent to the Dead.” Theological Studies, vol. 62, no. 2, 2001, pp. 262-282.

Dalton, Karen C.C. “Art for the Sake of Dynasty: The Black Emperor in the Drake Jewel and Elizabethan Imperial Imagery,” In Early Modern Visual Culture: Representation, Race, and Empire in Renaissance England, Edited by Peter Erickson and Clark Hulse. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000, pp. 178-214.

Danielson, Dennis. Paradise Lost and the Cosmological Revolution. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. 1000 Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. University of Minnesota, 1987.

Elden, Stuart. “Secure the Volume: Vertical Geopolitics and the Depth of Power,” Political Geography, vol. 34, 2013, pp. 35-51.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skins, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann. 1967. Pluto Press, 2008.

Fellmeth, Aaron X. and Maurice Horwitz. Guide to Latin in International Law. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Hale, John. A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft. Printed by B. Green, and J. Allen, for Benjamin Eliot under the town house, 1702.

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

Iton, Richard. “Still Life,” Small Axe, vol.17, no.1, 2013, pp. 22-39.

Joshi, Sunand T. A Dreamer and a Visionary: HP Lovecraft in His Time. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Karera, Axelle. “Blackness and the Pitfalls of Anthropocene Ethics.” Critical Philosophy of Race, vol. 7, no.1, 2019, pp. 32-56.

Keller, Catherine. The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming. Routledge, 2003.

King, Tiffany Lethabo. The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press, 2019.

Kister, Menahem. “Tohu wa-Bohu, Primordial Elements & Creatio ex Nihilo,” Jewish Studies Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 3, 2007, pp. 229-256.

Kragh, Helge S. Entropic Creation: Religious Contexts of Thermodynamics and Cosmology. Routledge, 2016.

Lamont, Rosette C. “Orphic Poets,” The Classical Outlook, vol. 49, no. 10, 1972, pp. 114-116.

Lifshitz, Yael R. “The Geometry of Property.” University of Toronto Law Journal, vol. 71, no.4, 2021, pp. 480-509.

Marriott, David. Whither Fanon?: Studies in the Blackness of Being. Stanford University Press, 2018.

McKittrick, Katherine. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Neocleous, Mark. “The Other Space of Police Power; or, Foucault and the No-Fly Zone.” In Foucault and the History of Our Present, Edited by Sophie Fuggle, et al. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 77-93.

Nicholls, Angus James. Goethe’s Concept of the Daemonic: After the Ancients. Camden House, 2006.

O’Donnell, S. Jonathon. “Witchcraft, Statecraft, Mancraft: On the Demonological Foundations of Sovereignty.” Political Theology, vol. 21, no. 6, 2020, pp. 530-549.

Pernety, Antoine-Joseph. Treatise on the Great Art: A System of Physics According to Hermetic Philosophy and Theory and Practice of the Magisterium. Edited by Edouard Blitz. Occult, 1898.

Pinilla, Ramón Mujica. “Angels and Demons in the Conquest of Peru,” In Angels, Demons and the New World. Edited by Fernando Cervantes and Andrew Redden. Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 171-210.

Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Translated by Steven Corcoran. London: Continuum, 2010.

Randles, William G.L. Geography, Cartography and Nautical Science in the Renaissance: The Impact of the Great Discoveries. Ashgate/Variorum, 2000.

Reiling, Jannes and Jan Lodewijk Swellengrebel. A Translator’s Handbook on the Gospel of Luke. Brill, 1971.

Ricciardi, Marcello. “ “He Haunts One for Hours Afterwards”: Demonic Dissonance in Milton’s Satan and Lovecraft’s Nyarlathotep,” The Hermeneutics of Hell, Edited by Gregor Thuswaldner and Daniel Russ. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 253-269.

Rikhof, Herwi. “Descensus ad Inferos: An Exercise in the Interaction Between Art and Theology.” Bijdragen 72, no. 2, 2011, pp. 123-160.

Schmitt, Carl. The Nomos of the Earth. Translated by G.L. Ulmen, 1950. Telos Press, 2003.

Schofield, Alfred T. “Time and Eternity,” Journal of the Transactions of the Victoria Institute, Or Philosophical Society of Great Britain, vol. 59, pp. 281- 301. Victoria Institute, 1927.

Sexton, Jared. Black Men, Black Feminism: Lucifer’s Nocturne. Springer, 2018.

da Silva, Denise Ferreira. “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞/∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value.” e-flux Journal, vol. 79, 2017.

da Silva, Denise Ferreira. “How.” e-flux Journal, vol. 105, 2019.

Sprankling, John G. “Owning the Center of the Earth.” UCLA Law Review, vol. 55, 2007, pp. 979-1040.

Stephenson, Jeffrey E. and Jerry S. Piven, “Hell Is For Children? Or The Violence of Inculcating Hell.” In The Concept of Hell, Edited by Robert Arp and Benjamin McCraw. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 127-145.

Thacker, Eugene. In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, vol. 1. Zero Books, 2011.

Thomas, William A. “Ownership of Subterranean Space,” Underground Space, vol. 3, no. 4, 1979, pp. 155-163.

Torchia, N. Joseph. Creatio Ex Nihilo and the Theology of St. Augustine: the Anti-Manichaean and Beyond. P. Lang, 1998.

Warren, Calvin L. Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation. Duke University Press, 2018.

Wilderson, Frank B. III, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms. Duke University Press, 2010.

Wynter, Sylvia. “1492: A New World View.” Race, Discourse, and the Origin of the Americas: A New World View, Edited by Vera Lawrence and Rex Nettleford. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995, pp. 5-57.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Genital Mutilation or Symbolic Birth—Female Circumcision, Lost Origins, and the Aculturalism of Feminist/Western Thought.” Case Western Reserve Law Review, vol. 47, no. 2, 1996, pp. 501-552.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation––An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3, 2003, pp. 257- 337.

Notes

- S. Jonathon O’Donnell, “Witchcraft, Statecraft, Mancraft: On the Demonological Foundations of Sovereignty.” Political Theology, vol. 21, no. 6, 2020, pp. 2.

- Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3, 2003, pp. 356. + Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

- William G.L. Randles, Geography, Cartography and Nautical Science in the Renaissance: The Impact of the Great Discoveries. Ashgate/Variorum, 2000.

- The 1587 English case Bury v. Pope documents one of the earliest citations of the maxim in European jurisprudence, but with an important modification. The superlative summitas was added so the phrase communicates that property spanned from topsoil to the atmosphere’s upper limit. Bury v. Pope’s plaintiff filed suit because the defendant’s home blocked his access to sunlight. Pope’s prerogative to erect buildings of any height were protected from other private landowners once the court ruled that the land the offending house was built upon was legally indivisible from space superjacentto it. Yehuda Abramovitch, “The Maxim Cujus Est Solum Ejus Usque Ad Coelum as Applied in Aviation.” McGill Law Journal, vol. 8, 1961, pp. 253.

- John G. Sprankling, “Owning the Center of the Earth.” UCLA L. Rev., vol. 55, 2007, pp. 981.

- For more detailed discussion on the ad coelum doctrine’s 20th-21st century significance, see Stuart Banner, Who Owns the Sky? The Struggle to Control Airspace from the Wright Brothers on. Harvard University Press, 2009. + Adrian J. Bradbrook, “Relevance of the Cujus Est Solum Doctrine to the Surface Landowner’s Claims to Natural Resources Located Above and Beneath the Land,” Adelaide Law Review, vol. 11, no. 4, 1988, pp. 462-483. + Yael R. Lifshitz, “The Geometry of Property.” University of Toronto Law Journal, vol. 71, no.4, 2021, pp. 480-509. + Mark Neocleous, “The Other Space of Police Power; or, Foucault and the No-Fly Zone.” In Foucault and the History of Our Present, Edited by Sophie Fuggle, et al. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 77-93. + Sprankling, 2007.

- Aaron X. Fellmeth and Maurice Horwitz, Guide to Latin in International Law. Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 69, pp. 285.

- Here inferos is replaced by infernos: “…the maxim Cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et ad infernos was coined, meaning “The owner of the surface also owns to the sky and to the depths”.” William A. Thomas, “Ownership of Subterranean Space.” Underground Space, vol.3, no. 4, 1979, pp. 156.

- Martin F. Connell, “Descensus Christi ad Inferos: Christ’s Descent to the Dead.” Theological Studies, vol. 62, no. 2, 2001, pp. 264, Footnote 3.

- Jeffrey E. Stephenson and Jerry S. Piven, “Hell Is for Children? Or The Violence of Inculcating Hell. In The Concept of Hell, Edited by Robert Arp and Benjamin McCraw. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 143, Footnote 2.

- Stuart Elden, “Secure the Volume: Vertical Geopolitics and the Depth of Power,” Political Geography, vol. 34 2013, pp. 47.

- Lifshitz, pp. 5.

- Sylvia Wynter, “Genital Mutilation or Symbolic Birth—Female Circumcision, Lost Origins, and the Aculturalism of Feminist/Western Thought.” Case Western Reserve Law Review, vol. 47, no. 2, 1996, pp. 546.

- Stuart Clark, Vanities of the Eye: Vision in Early Modern European Culture. Oxford University Press, 2007, pp. 12.

- Jacques Rancière, Translated by Steven Corcoran. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Continuum, 2010, pp. 80.

- Jared Sexton, Black Men, Black Feminism: Lucifer’s Nocturne. Springer, 2018, pp. 18.

- Rancière, pp. 71-2.

- Rancière, pp. 42-3.

- Connell, pp. 266-8.

- David Marriott, Whither Fanon?: Studies in the Blackness of Being. Stanford University Press, 2018.

- John Hale, A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft (1702), pp. 44-6.

- Hale, pp. 13-4.

- Angus James Nicholls, Goethe’s Concept of the Daemonic: After the Ancients. Camden House, 2006, pp. 11-12.

- Alfred T. Schofield, “Time and Eternity,” Journal of the Transactions of the Victoria Institute, Or Philosophical Society of Great Britain, vol. 59, Victoria Institute, 1927, pp. 285.

- Jannes Reiling, et al. A Translator’s Handbook on the Gospel of Luke. Brill, 1971, pp. 189-90.

- N. Joseph Torchia, Creatio Ex Nihilo and the Theology of St. Augustine: the Anti-Manichaean and Beyond. P. Lang, 1998, pp. 100.

- Catherine Keller, The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming. Routledge, 2003, pp. 200.

- Keller, pp. 200.

- Gay L. Byron, Symbolic Blackness & Ethnic Difference in Early Christian Literature. Routledge, 2002, pp. 45.

- David Brakke, “Ethiopian Demons: Male Sexuality, the Black-Skinned Other, and the Monastic Self.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 10, no. 3/4, 2001, pp. 507.

- Herwi Rikhof, “Descensus ad Inferos: An Exercise in the Interaction between Art and Theology.” Bijdragen, vol. 72, no. 2, 2011. pp. 145.

- Sexton, pp. 15-16.

- Menahem Kister, “Tohu wa-Bohu, Primordial Elements & Creatio ex Nihilo,” Jewish Studies Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 3, 2007, pp. 230.

- Kister, pp. 232.

- Kister, pp. 236.

- Kister, pp. 229.

- Tina Beattie, Theology After Postmodernity: Divining the Void—A Lacanian Reading of Thomas Aquinas. Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 308.

- Helge S. Kragh, Entropic Creation: Religious Contexts of Thermodynamics and Cosmology. Routledge, 2016, pp. 16.

- Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth, pp. 87.

- Ramón Mujica Pinilla, “Angels and Demons in the Conquest of Peru,” In Angels, Demons and the New World. Edited by Fernando Cervantes and Andrew Redden. Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 193.

- Sylvia Wynter, “Columbus and the Poetics of the Propter Nos,” Annals of Scholarship, vol. 8, no. 2, 1991, pp. 255.

- Sylvia Wynter, “1492: A New World View.” Race, Discourse, and the Origin of the Americas: A New World View, Edited by Vera Lawrence and Rex Nettleford. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995, pp. 26.

- Wynter, “1492,” pp. 26.

- Lyndy Abraham, A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery. Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 3.

- Denise Ferreira da Silva, “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞/∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value,” e-flux Journal, vol. 79, 2017.

- Richard Iton, “Still Life,” Small Axe, vol.17, no.1, 2013, pp. 39.

- Keller, pp. 86.

- Abraham, pp. 3.

- Denise Ferreira da Silva, “How,” e-flux journal, vol. 105, 2019.

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann. Pluto Press, 1967, 1986, 2008, pp. 112.

- Frank B. Wilderson, III, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms. Duke University Press, 2010, pp. 79.

- Fanon, pp. 144.

- Fanon, pp. 144.

- Antoine-Joseph Pernety, Treatise on the Great Art: A System of Physics According to Hermetic Philosophy and Theory and Practice of the Magisterium. Occult Pub. Co., 1898, pp. 33.

- Abraham, pp. 3.

- Karen C.C. Dalton, “Art for the Sake of Dynasty: The Black Emperor in the Drake Jewel and Elizabethan Imperial Imagery,” In Early Modern Visual Culture: Representation, Race, and Empire in Renaissance England, Edited by Peter Erickson, and Clark Hulse. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000, pp. 199.

- Rosette C. Lamont, “Orphic Poets,” The Classical Outlook, vol. 49, no. 10, 1972, pp. 115.

- Frederick A. de Armas, “The King’s Son and the Golden Dew: Alchemy in Calderón’s La Vida Es Sueño,” Hispanic Review, vol. 60, no. 3, 1992, pp. 309.

- Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016, pp. 169.

- Marcello Ricciardi, “‘He Haunts One for Hours Afterwards’: Demonic Dissonance in Milton’s Satan and Lovecraft’s Nyarlathotep,” The Hermeneutics of Hell, Edited by Gregor Thuswaldner and Daniel Russ. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 253-269, pp. 253-4.

- Sunand T. Joshi, A Dreamer and a Visionary: HP Lovecraft in his Time. Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 71-2.

- Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, Zero Books, 2011, pp. 156-7.

- “Transversal communications between different lines scramble the genealogical trees. The rhizome is an anti-genealogy.” Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. 1000 Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. University of Minnesota Press, 1987, pp. 11. + “The Gorgons are powerful winged chthonic entities without a proper genealogy; their reach is lateral and tentacular; they have no settled lineage and no reliable kind (genre, gender)…” Haraway, pp. 53.

- Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press, 2019, pp. 99.

- Haraway, pp. 71.

- Axelle Karera, “Blackness and the Pitfalls of Anthropocene Ethics.” Critical Philosophy of Race, vol. 7, no. 1, 2019, pp. 32-56.

- Wynter, “1492”, pp. 5.

- Haraway, pp. 168.

- Calvin L. Warren, Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation. Duke University Press, 2018, pp. 9.

- Wilderson, pp. 14.

Cite this Essay

Cooper, Cecilio M. “Fallen: Generation, Postlapsarian Verticality + the Black Chthonic.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 38, 2022, doi:10.20415/rhiz/038.e01