Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 40 (2024)

The criminal in the prison-house of language: Conceptual writing to re-present Havelock Ellis’ use of “the criminal” in his book, The Criminal

Kurt Borchard

University of Nebraska Kearney

Abstract: Criminology has historically promoted positivism, a disciplinary orientation producing reward structures for some researchers committed to deductive work rooted in developing concepts, hypothesizing relationships, and empirical testing. Its is useful, then, to review where such tendencies were initially conceived and promoted. Havelock Ellis’ 1890 book The Criminal, a then-seminal review of literature in criminal anthropology, concerns many topics involving criminals and criminality. In the following conceptual writing, I present here, verbatim, all instances where Ellis uses the exact phrase “the criminal” in his book, along with any words following the phrase in the sentence. The resulting text then deconstructs and re-imagines the true object of Ellis’ work: the creation of the supposed object of his study as self-evidently Real, existing outside of linguistic and discursive parameters. Ellis as detective (searching for the criminal everywhere but right under his writing nose) could never fully apprehend his ever-escaping subject. Yet, through discourse, Ellis and his fellow criminal anthropologists laid claim as those best qualified for establishing the criminal’s essential identity, an ideal type still pursued through government funded criminological research.

The rationale for and purpose of this conceptual writing project

A significant branch of criminology as a field today promotes positivism, or applying methods from the natural sciences toward making causal claims about social life and behavior. Deductive logic provides a cornerstone to create conceptual apparatuses toward rigorously defining concepts and their relationships in order to explain crime, relationships that are then tested empirically (see Gottfredson and Hirschi, 1987). Early studies using this approach aimed to identify and distinguish “criminals” from “non-criminals” (see Lombroso and Ferri, 1911). Subsequently, U.S. government-funded crime research grew, and continued, emphasizing individual rather than structural explanations, at least into the 1990s (Dowdy, 1994). Scientific attempts at objectifying, identifying, understanding, and then creating policy concerning “the criminal” are further evident today, for example, in a work like Stanton Samenow’s The Criminal Mind (2014). Research generally framed as concerning “the criminal” or specific types of criminals (murderers, rapists, terrorists, or other types) are also being pursued today through government-funded studies in fields like genetics and neurocriminology (Raine, 2013). For many governmental grants or other forms of institutional funding, positivism then serves as an institutionally pre-approved paradigmatic framework for research (Raine, 2013).

Positivism within criminology is therefore a tradition influencing and legitimating the field’s reward structure (or what forms of research and what basis for findings more likely lead to being considered serious and rigorous and promoting occupational prestige). Such an approach creates a supposedly self-evident framework and discourse particularly unresponsive to deconstructive critiques (despite Michel Foucault ironically writing volumes about crime and responses to it). There is, in sum, limited reflexivity in positivist-focused criminology about science as a discourse and its preferred methodology.

Contemporary projects in positivist criminology pitched toward governmental funding are often not presented exclusively or fully about crime and understanding criminals and their behavior, so much as having applicability to understand broader human tendencies. A study of, for example, impulsivity, might then be emphasized as having import for criminology, as one component necessary for further scientific understanding, the ultimate result of which is thought of as necessary for any project oriented toward a cumulative understanding of criminals and how crime occurs. The study of human tendencies as applicable to understanding crime, though, is unsuited toward considering extra-scientific elements also central to the study of crime, such as crime being socially defined through ever-evolving law, or criminal acts involving complex considerations of free will, or thoughts concerning individual social responsibility, or noting the evolving role of technology in crime and criminal behavior, or even simply observing the role of context in, and for, behavior (Siegel, 2017). A denial or minimization of the effects of such subjective considerations then gives lie to the idea that positivist-oriented criminology as a science is a cumulative enterprise. This institutional framework promotes researchers operating within a particular area of criminology (and working during their unique historic era) to take up the mantle of a paradigm, one where researchers later attempt to refine, augment, or perhaps even (eventually) abandon that way of conceptualization and framing (Kuhn, 1996).

Through the following conceptual writing project rooted instead in artistic and literary approaches, I then hope to turn a mirror on foundational texts in criminology as well as on contemporary practices for positivist practitioners in the field. Early scientific writing set the stage for work to reify and decontextualize, to various extents, the subjects they pursued. The analysis of such foundational writing, when presented as I do here in a creative, re-contextualized way, can reveal as much about their creators and the assumptions once (and in some respects, still) dominant within a field as such work reveal about their “subjects.”

The conceptual writing I present here pictures the true subject of Havelock Ellis’ (1890, original edition) book, The Criminal. Ellis’ book, published under The Contemporary Science Series (also edited by Ellis), is considered a foundational text in the then-emergent field of criminal anthropology. Here, I present The Criminal’s criminal. Ostensibly “the criminal” is, in precise terms, the exact object of Ellis’ study. “The criminal,” singular, is an ideal type, whereas the phrase “criminals,” plural, can be an ideal type but can also refer to specific groups, and individuals, and bodies. This experimental writing here then presents what Ellis thought, or argued that, he was studying and/or reviewing but was in fact, through his book, creating. The criminal becomes reified, Other-ed, toward comprehensibility, yet is also a dangerous, elusive, shape-shifting figure, and (therefore) a topic of great social concern requiring ongoing research presented by Ellis as best accomplished by scientist-experts. The criminal for Ellis became a self-evident thing, an objective type encompassing a convolution of things like behavior, personal outlook, descriptions, an individual’s stated thoughts, and various writing. In establishing the new field for English speakers, Ellis’ book, though, was a keystone in developing the discourse that constituted, in the social sciences, the criminal.

Regarding my approach, conceptual writing is a form of writing that, like conceptual art, begins with a set of rules to be followed, which then allows writing to be produced as by a machine (Dworkin and Goldsmith, 2011). Conceptual writing is based on following pre-established rules to automate the writing process. Developing this conceptual writing project beginning with the title page, I took each of the sentences from Ellis’ book that contained the phrase “the criminal,” along with all the subsequent words until the end of the sentence. I cut and pasted them into a single document. I then present each as a single, stand-alone line, in the order in which they appear in the original.

Who then, or what, is this figure called the criminal? Although the hope in such nascent social science was to try and study people as if their behavior was reducible to as-yet-to-be-discovered laws, Ellis’ discourse reveals that the always-already imbedded social base of the project is to be studiously ignored in favor of statements of scientific authority. Through reimagining Ellis’ work we learn many things: the criminal can be man, woman, organization, microbe, lunatic, skull, face, nose, breast, character, type, countenance, class, family, law, parent, and trial (a puzzling, dizzying, and entertaining form of organization and sense-making). The criminal possesses wildly divergent, contradictory, and cumulatively nonsensical characteristics within a field of incommensurate discourses and topics. There are types of criminals, and types within types. Through such presentations Ellis, ultimately, wants to capture the criminal. Yet with each attempt at articulation, his language falls further behind in the discourse it has produced. His text reveals that the center-less-ness of the scientifically assessed criminal creates an entity whose existence is at once present and endlessly deferred, one both socially threatening and impossible to constrain or subject to discipline.

The conceptual writing introduced here is also destabilizing, as the reader does not know what words in a given sentence precede the words “the criminal” (if indeed the words appear in a sentence rather than simply being the phrase as a stand-alone like in a heading or subheading, each of which I also reproduced here verbatim). The words “the criminal” have been harvested for this project, just as the idea of such a figure and review of other’s literature were harvested by Ellis. “The criminal” in Ellis’ work can also be seen as a remix, as an amalgam concerning an entity taken out of context, re-contextualized, and re-framed, as an ideal type. Ellis’ goal, then, is to capture “the criminal” through creating a useful document toward a positivistic policy implication: that future criminal bodies might then be recognized, captured, and contained, in the hope of preventing further criminality. My goal, by contrast, is to deconstruct not simply Ellis’ criminal, but also the contemporary foundation and ongoing institutional legitimization of positivist criminological research.

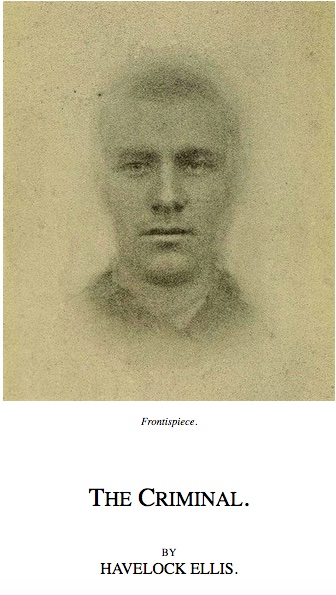

Of further importance, the imaginative figure in Ellis’ book is also represented pictorially near the book’s cover, through the then relatively new process of photography presented as a form of documentary realism achieved through advanced technology and natural processes (involving light, lenses, machinery, chemicals, and paper). Drawing from Francis Galton, Ellis’ book presented composite portraits of criminals, or blends of multiple photographs where the center point (with the most common features) is the sharpest, and the image then blurring outward to represent features with the least overlap (Stephens, 2013). Ellis himself therefore uses such a conceptual photograph as a science-based approach to introduce readers to the subject in/of his book—the frontispiece image in his book represents a composite of criminal “dullards” from Elmira Reformatory in 1890. The photograph at the beginning of Ellis’ book provides a documentary, empirically-derived basis in visual evidence of the characters he will also attempt to pin down empirically. The growing eugenics movement at the time could then use photography, rooted in a scientific, technology-based, objective reality, as a way of revealing such ideal types (Green, 1984). Composite images of those with shared criminal features might well be seen as a form of predictive algorithm, becoming perfect for future “wanted posters,” an image of someone the average citizen should be “on the lookout” for, someone who, perhaps even unbeknownst to themselves, are revealed as criminals-in-wait through their shared, now newly framed, biological tells.

Through its combination of advanced photographic techniques and summarized literature on criminal anthropology, Ellis’ book was praised by the prestigious journal Science as timely and accessible (Science, 1890). The criminal was then emerging as a frightening figure and researchable topic, one that must be addressed, understood and dealt with, a need that in the nineteenth century began being framed as the subject of scientific discourse, (supposedly neutral) systematic empirical observation, and expert knowledge. The object of Ellis’ study could then be placed and addressed under the realm of what Foucault (in his later work) called governmentally, a bureaucratically-organized political (and at times, bio-political) response in line with the developing technocratic society, one presented as operating in the rational, best interest of all (Foucault, 2003).

The conceptual piece presented here also concerns how a category becomes created through the use of criteria in discourse designating the object being studied. Part of what I produced below are many instances/iterations of Ellis’ title as it is found in headings and subheadings throughout his book; the repeating title phrase then creates in this writing project, and in the original text, a ritualistic grounding mantra of the thing (presumably) being understood. Such repetition then also creates a sense of moral panic and the object of study as both self-evident and not—it requires an entire book (and what for Ellis was surely years of study) summarizing other books (involving their own years of study) to (try to) encompass what the category (and its supposed sub-categories) contains.

The textual exercise below, targeting the shape-shifting figure, topic, and orientation of “the criminal” for Ellis, reveals that the true subject of his work is his fiction in trying to fix an identity and type. The criminal can also then here be considered “captured” in what Fredric Jameson called “the prison-house of language” (1975). I implicitly referenced the title of Jameson’s book (a book focused on the limits of Russian Formalism and Structuralism) in my own article’s title to understand Ellis’ text as attempting to delimit his creation through a self-referential system of words.

Before beginning to read this experimental work, a note to the reader: some might find a traditional, word-for-word reading of the conceptual text to be tedious. Practitioners of conceptual writing make it clear that readability is not precisely the goal of such work. Kenneth Goldsmith has observed that conceptual writing “is more interested in a thinkership rather than a readership . . . Conceptual writing is good only when the idea is good; often, the idea is much more interesting than the resultant texts” (2008: n.p.). In other words, “reading” the following work here might involve dipping into, skimming, and/or contemplating the project. Finally, I should note that, considering my use of the original text presented here, the material falls in the public domain (no longer subjected to copyright law), and is therefore fully reproducible.

From: The Criminal, by Havelock Ellis (1890) (all capitalization and italics in the original)

THE CRIMINAL.

The Criminal.

the Criminal

the Criminal.

the criminal as he is in himself and as he becomes in contact with society; it also tries to indicate some of the practical social bearings of such studies.

THE CRIMINAL.

the criminal by passion.

The criminal by passion never becomes a recidivist; it is the social, not the anti-social, instincts that are strong within him; his crime is a solitary event in his life.

the criminal by passion cannot complain that he in his turn becomes the victim of a social reaction.

the criminal by passion can be recognised at once when we know his history.

the criminal who is insane in the strict and perhaps the only legitimate sense of the word—i.e., intellectually insane.

the criminal in the proper sense, the criminal with whom we shall be chiefly concerned.

the criminal with whom we shall be chiefly concerned.

the criminal.

the criminal aristocracy.

the criminal is the instrument that executes them.

the criminal is the microbe, an element which only becomes important when it finds the medium which causes it to ferment: every society has the criminals that it deserves.”

the criminal man.

THE CRIMINAL.

the criminal man from the average man.

the criminal is a criminal by nature he ought to be destroyed, not in revenge, but for the same reason that scorpions and vipers are destroyed.

the criminal that he was of pallid complexion, with long hair, large ears, and small eyes, and he proceeded to give the characteristics of various classes of criminals, his observations often showing keen insight.

the criminal organisation, and even to its varieties, many of his observations according well with the results of recent investigation.

the criminal which is now widely regarded as the only right and reasonable method.

the criminal who followed him all insisted on the pathological element.

the criminal and the lunatic are identical, and both equally irresponsible.

the criminal.

the criminal is not necessarily an insane or diseased person, and he showed that his abnormality is not of the kind that intellectual education can remedy.

the criminal as “morally mad,” and therefore irresponsible.

the criminal, being morally insane and usually incurable, should be treated in the same way as the intellectually insane person.

the criminal throughout Europe.

the criminal, the unstable, emotional element in him, his proneness to delusions, his insensibility, and his weak-mindedness.

the criminal.

the criminal; the Zanardelli criminal code, which has recently become law, while by no means entirely satisfactory from the scientific point of view, shows the influence of the new movement.

the criminal man as a human variety, while Lombroso’s own manifold studies and various faculties had given him the best preparation for approaching this great task.

the criminal that had appeared before Lombroso, was partial; the criminal was therein regarded purely as a psychological anomaly.

the criminal as, anatomically and physiologically, an organic anomaly.

the criminal in nature, his causes, and his treatment.

the criminal, and at a later date he has pressed too strongly the epileptic affinities of crime.

the criminal constitutes the only reasonable legal criterion to guide the inevitable social reaction against the criminal.

the criminal.

the criminal man will, it is probable, for all practical purposes, supersede other works.

the criminal may be said to have begun with Krafft-Ebing, the distinguished professor of psychiatry, now at Vienna, who, by laying down clearly in his Grundzuge der Kriminal Psychologie (1872), and other works, the doctrine of a criminal psychosis, and pointing out its practical results, deserves, as Krauss remarks, to be regarded as an important precursor of Lombroso.

the criminal brain, in which he observed frequent confluence of the fissures, as among some lower races, and also an additional convolution in the frontal lobe, which he assimilated to that of the carnivora.

the criminal, to establish the degree of his dangerousness and of his responsibility, and to effect the gradual and progressive reform of penal law in accordance with the principles of the new school.”

the criminal.

the criminal, to the medical officers of the larger prisons in Great Britain and Ireland, the answers that I received, while sometimes of much interest—and I am indebted to my correspondents for their anxiety to answer to the best of their ability—were amply sufficient to show that criminal anthropology as an exact science is yet unknown in England.

the criminal.

the criminal.

the criminal belongs; those of long-headed race being sometimes very long, and those of broad-headed race sometimes very broad; the Corsican criminal being often very dolichocephalic, and the Breton criminal often very brachycephalic.

the criminal skull, although it has not often at present been subjected to exact measurement.

the criminal than in the ordinary series.

the criminal woman is compared with the normal woman, she is found to approach more closely to the normal man than the latter does; while the corresponding character (feminility) is not found so often in the criminal as in the normal man, except among pæderasts and some thieves.

the criminal as in the normal man, except among pæderasts and some thieves.

the criminal face, both in men and women.

the criminal resembles the savage and the prehistoric man; among the insane the jaw weighs rather less than the normal average.

the criminal.

the criminal man.

The criminal nose has been measured and studied with great care and enthusiasm by Ottolenghi.

the criminal nose in general is rectilinear, more rarely undulating, with horizontal base, of medium length, rather large and frequently deviating to one side, and he describes several varieties.

the criminal than in the non-criminal person, and this must have struck many persons who have seen a large number of criminals or photographs of criminals.

the criminal, in relation not only to the normal man but even to the epileptic and the cretin.

the criminal differs greatly from the ordinary professional man, in whom baldness is frequently found.

the criminal anthropologists of to-day were long ages back crystallised by the popular intelligence.

the criminal character of young people whom as yet no one had suspected.

the criminal type; a little girl of twelve also selected the same.

the criminal countenance which is at once repulsive and interesting.

the criminal physiognomy is that it is to a large extent independent of nationality.

the criminal expression there is much divergence of opinion.

the criminal physiognomy which has often been quoted, speaks of it as branded by the hand of nature.

the criminal whose fate is being argued.

the criminal family, first mentioned by Despine in his Psychologie Naturelle, is interesting in this connection.

the criminal-law prisoners, assuming at once, in virtue of I do not know what equivocal predestination, their language, their appearance, their habits, their mental dispositions, even the same negative morality, savagery, treachery, artfulness, rapacity, and unnatural vice.”

the criminal parent tends to produce a criminal child.

the criminal tradition is carried on through many generations and with great skill, a kind of professional caste being formed.

The criminal is exposed to many of the influences which lead the savage to adopt the practice, the chief of which have been already enumerated; this is a sufficient explanation of the similarity of habit, and it seems scarcely accurate to describe it as atavism.

the criminal has indeed been observed by every one who is familiar with prisons.

the criminal than in the normal person, and slightly less in the criminal women than in the criminal men.

the criminal women than in the criminal men.

the criminal men.

The criminal women also showed a larger proportion of gustatory obtuseness than the normal women.

the criminal to various thoughts and emotions, Lombroso made a series of very interesting experiments, during the course of a year, with the sphygmograph and with Mosso’s ingenious and valuable instrument, the plethysmograph.

the criminal are of the first importance, and it is necessary that they should be greatly extended and carefully checked.

the criminal is markedly deficient in physical sensibility.

the criminal breast.

the criminal approximates to the savage, he is at the same time related to those more or less civilised persons who tolerate killing with equanimity when it is called war.

the criminal are in reality closely related, and they approximate him to savages and to the lower animals.

the criminal is lacking in curiosity, the foundation of science, and one of the very highest acquisitions of the highly-developed man.

the criminal: like the cat, indolent and capricious, yet ardent in the pursuit of an aim, the anti-social being knows only how to satisfy his impulsive instincts.”

the criminal is naturally bright.

the criminal sometimes leads him to commit the imprudence of talking about his plans beforehand, and so courting detection.

the criminal shows itself in the artistic or dramatic representations which he makes of his crime.

The criminal everywhere is incapable of prolonged and sustained exertion; an amount of regular work which would utterly exhaust the most vigorous and rebellious would be easily accomplished by an ordinary workman.

the criminal impossible.

the criminal is capable of moments of violent activity.

The criminal craves for some powerful stimulus, excitement, uproar, to lift him out of his habitual inertia.

the criminal to be must have some powerful stimulant to take him out of himself, to give him a joy which is otherwise beyond his grasp, and alcohol is the stimulant which comes easiest to hand.

The criminal finds another strong form of excitement in gambling.

the criminal is confined alone, or with persons of the same sex, serves to develop perverted sexual habits to a high degree.

the criminal and his intimate ally, the prostitute.

The criminal appreciates sympathy.

the criminal.

the criminal condemned to death fails to avail himself of the ministrations of the chaplain (only once in more than thirty years at La Roquette), and frequently to respond to them with gratifying eagerness.

the criminal is not superstitiously devout, he is usually stupidly or brutally indifferent.

the criminal transforms living forms into things, assimilates man to animals.”

The criminal instinctively depreciates the precious coinage of language, just as to his imagination money is at Paris “zinc,” and in the Argentine Republic “iron.”

The criminal slang of France and Italy has been studied in its psychological bearings much more thoroughly than the English, by Mayor, Lombroso, and others.

the criminal is most intimately interested by noting the wealth and variety of synonyms for certain words.

the criminal keeps silent his most intimate thoughts, he feels himself compelled to fix them wherever he may find himself, on the walls of his prison, or on the books that are lent to him.

the criminal as well as the man of genius.

the criminal is glorified, as well as the minute knowledge of criminal arts disseminated by newspapers, have a very distinct influence in the production of young criminals.

the criminal tries to find literary expression for himself.

the criminal or the man of genius is most prominent.

the criminal in prison, and to which he seeks, by such means as may be within his reach, to give artistic expression.

the criminal in his own eyes is that he is quite certain that the public opinion of the class in which he was born and lives will acquit him; he is sure that he will not be judged definitely lost unless his crime is against one of his own class, his brothers.

the criminal to take so lofty a standpoint as this; more usually he bases the justification for his own existence on the vices of respectable society—“the ignorance and cupidity of the public,” as one prisoner expressed it—that he is shrewd enough to perceive; “it is a game of rogue catch rogue,” a convict told Mr. Davitt.

The criminal is firmly convinced that his imprisonment is a sign that the country is going to the dogs.

the criminal mind, and one meets it at every turn.

the criminal songs still found in Sardinia there is one (quoted by Lombroso from Bouillier’s Les Dialectes et les Chants de la Sardaigne) that may be quoted here.

the criminal justifies himself, not on moral grounds, but as a man of the world: “You regret the robbery that I have committed, and you call it a bad action; the insignificant act for which I have been condemned is the first link in a chain which will not, I hope, finish so soon.

the criminal up to the present date by many workers in various lands.

the criminal in nature may seem to be somewhat cautious and tentative, it must be remembered that we are still slowly feeling our way to firm ground.

the criminal, and on his treatment and prevention.

the criminal, the consideration of which will lead us naturally to a clearer view of the criminal’s position.

the criminal woman as distinct from the criminal man, (d) the relation of crime to vice, (e) crime as a profession, (f) the relations of crime to epilepsy and insanity.

the criminal man, (d) the relation of crime to vice, (e) crime as a profession, (f) the relations of crime to epilepsy and insanity.

the criminal such a classification can be upheld, and Lomboso himself speaks with less than his usual decision.

the criminal, and the strongly marked social reaction that we see here shows that the castors have recognised this.

The criminal is an individual whose organisation makes it difficult or impossible for him to live in accordance with this standard, and easy to risk the penalties of acting antisocially.

the criminal, a certain psychical and even physical element belonging to a more primitive age is simple and perfectly reasonable.

the criminal has to live in a country where the majority of the inhabitants have learned new lessons of life, and where he is regarded more and more as an outcast as he strives more and more to fulfil the yearnings of his nature.”

“The criminal of to-day is the hero of our old legends.

the criminal is well known; while Colajanni, in many respects an opponent of Lombroso, remarks: “How many of Homer’s heroes would to-day be in a convict prison, or at all events despised as violent and unjust.”

the criminal, than the adult.

the criminal, we may often take it, there is an arrest of development.

The criminal is an individual who, to some extent, remains a child his life long—a child of larger growth and with greater capacity for evil.

the criminal tradition, the younger sons become paupers or vagabonds, and the sisters become prostitutes.

The criminal is simply a person who is, by his organisation, directly anti-social; the vicious person is not directly anti-social, but he is indirectly so.

The criminal directly injures the persons or property of the community to which he belongs; the vicious person (in any rational definition of vice) indirectly injures these.

the criminal groups; they present a comparatively small proportion of abnormalities; their crimes are skilfully laid plots, directed primarily against property and on a large scale; they never commit purposeless crimes, and in their private life are often of fairly estimable character.

the criminal may be explained by the influence of profession.

the criminal physically as well as morally.”

The criminal is, however, by no means an idiot.

the criminal in his most clearly-marked form—the instinctive criminal.

the criminal has been regarded as a kind of algebraic formula, to use Professor Ferri’s expression; the punishment has been proportioned not to the criminal but to the crime.

the criminal but to the crime.

the criminal as a natural phenomenon, the resultant of manifold natural causes.

THE CRIMINAL.

the criminal; he was a normal person who had chosen to act as though he were not a normal person—a vine, as it were, that had chosen to bring forth thorns—and it was the business of the penologist to apportion the exact amount of retribution due to this extraordinary offence, with little or no regard to the varying nature of the offender; he was regarded as a constant factor.

the criminal class, expatiated, somewhat to their astonishment and much to their gratification, on the iniquity of giving a severe punishment for a theft that was petty, even though it had been preceded by many thefts and convictions.”

the criminal; in its crudest form it is Lynch law; in its highly developed form it shows itself in the elaborate training bestowed on the criminal at Elmira.

the criminal at Elmira.

the criminal.

the criminal—the prison and another, still more decisive, appearing in various forms, the cross, the stake, the gallows, the axe.

the criminal really dreads, and tells of offenders who committed their crimes under the impression that capital punishment had been abolished, and that they were to be provided with food and shelter for the rest of their lives.

the criminal, or even the welfare of society; it is a tender regard for the sentiments of the general public.

the criminal is never satisfactory, because we do not kill his accomplices, bad social conditions and defective institutions; we leave untouched the false social sentiments that urged the unmarried girl to kill her own child, or the rigid marriage system that made it easier for the man to kill his wife than to leave her or to allow of her leaving him.

the criminal.”

the criminal classes in England writes: “Looking at our present system of dealing with thieves, examining it from every side, it is clear that nothing can be more clumsy and inefficient—except for evil.

the criminal by the sentence he imposed.

the criminal, writes:—“Suppose that in some legendary country an austere king forbade all flirtation with married ladies, and that the punishment threatened to the guilty one should be a prohibition to leave during several weeks a certain club, a magnificent hotel, with gardens and terraces, where this gentleman would find his best friends, his old comrades at board and game, who, far from blaming him, would be glad to do the same.

the criminal,” remarks Dr. Paul Aubrey, in a recent and able study, Le Contagion du Meutre, “that is a myth; the prison is still the best school of crime which we possess.”

the criminal slang of various nations with its friendly synonyms for the prison is very significant on this point.

the criminal courts are prevented from awarding any sentence between two years, the longest period of imprisonment, and five years, the shortest legal sentence of penal servitude.

the criminal which is at once safe, reasonable, and humane.

the criminal, in all his manifold variations, with his ruses, his instinctive untruthfulness, his sudden impulses, his curiously tender points, is just as difficult to understand and to manage as the hospital patient, and unless he is understood and managed there is no hope of socialising him.

the criminal need not be entirely in the hands of officers the greater part of whose time is passed within the prison.

the criminal and the outside world must be to some extent broken down.

The criminal cannot be too carefully secluded from his fellow-criminals, neither can he have too much of outside socialising influence, if he is to be won back from the anti-social to the social world.

the criminal thoroughly, so as to learn at once how to treat him and how to protect ourselves from him, we must have a certain amount of access.

the criminal from his fellows.

the criminal a reasonable human being is as rational as to suppose that it will tend to make him a soldier or a sailor, a doctor or a clergyman.

the criminal is concerned—the mistake, that is, of supposing that at all points he is an average human being.

the criminal.

the criminal which are being carried on at Elmira are probably of more wide-reaching significance than any at present carried on elsewhere.

the criminal.

the criminal which coexist generally in the United States.

the criminal, there can be no doubt as to the value of its contribution to this difficult problem.

the criminal, without his excuse of a morbid or defective organisation.

the criminal should be bound to repair the damage he had caused.

the criminal which have been reviewed in this chapter:

the criminal.

the criminal himself is ignored.

the criminal comes in for discussion it is merely as a subject for sensational excitement, or unwholesome curiosity, as a creature to be vituperated or glorified without measure.

The criminal has always been the hero, almost the saint, of the uncultured.

the criminal is concerned, even in the most civilised country.

the criminal.

the criminal for his most powerful intercession in Heaven.

The criminal is a person endowed with divine force, to be treated with awe and reverence, and whose blood and flesh have something of the old sacramental power of infusing the divine one’s energy into the body of him who eats of it.

the criminal still survives.

the criminal as a hero or a saint after we have once seriously begun to study his nature.

the criminal.

the criminal.

the criminal is sane or insane.

the criminal.

the criminal, as I have already pointed out, and would again insist, cannot be attained by a mere administrative fiat; nor is it desirable that they should be.

the criminal population has increased since the war, relatively to the population, by one-third.

the criminal, among whom Ferri in this respect stands first, have seen the direct bearing on criminality of what Colajanni has called Social Hygiene.

the criminal.

the criminal is a diseased person, he held, or a lunatic, and we must consider the molecular troubles of the cerebral substance as well as the external physical signs.

the criminal must be subordinated to the same rules as the diagnosis of a disease; that is to say, it is made up of related and simultaneous conditions.

the criminal, just as a single symptom will not prove typhoid fever.

the criminal is a microbe which only flourishes in a suitable soil.

the criminal; but, like the cultivation medium, without the microbe it is powerless to germinate crime.

the criminal, but with his classification, and in criminal anthropology we must give the first place to psychology.

the criminal, although it is necessary also to consider his physical nature; while sometimes even the character of the crime is sufficient to class the criminal.

the criminal.

the criminal, and the method of repression.

the criminal can alone enlighten justice.

the criminal, just as the most senseless act is not enough to characterise a lunatic.

The criminal ought not to be able to say to his judge: “Why have you not made me better?”

the criminal trial from the sociological point of view.

the criminal and the insane.

the criminal who acts in accordance with his native and not morbid character.

the criminal

the criminal.

the criminal

the criminal, being a man of primitive organisation, will naturally exercise the brutality and lack of consideration which belong to a lower race.

the criminal is often very sensitive.

Discussion of the conceptual writing project

The experimental writing and creative presentation above can be read in many ways. The conceptual writing project usefully allows readers to contemplate single sentences or phrases that, when isolated and read against each other, cumulatively illustrate how early scientific work employed frames through which the topics were not simply studied but created. In his 1970 book The Order of Things, Foucault considered how, when he read a story by Borges, he encountered a system for ordering objects that to him seemed remarkably strange:

This passage quotes a ‘certain Chinese encyclopaedia’ in which it is written that ‘animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) suckling pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.’ (Foucault, 1970, p. xv)

Foucault states the passage made him laugh because it demonstrated “the exotic charm of another system of thought . . . the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that” (1970, p. xv, emphasis in original).

As Foucault noted, the story as a foil reveals the cultural and historical rootedness of all categorization systems, forms of understanding, and the potential bizarreness of those unifying fields and organizing principles to an uninitiated reader. If you take away the system whereby things are organized, the plurality and possibilities of organization are revealed, while current arrangements emerge as imbued with (and stifled or directed by) a series of historically-based power relations concerning what is to be organized, in what way, and for what purpose. In The Order of Things, Foucault then went on to consider how the historical evolution, and the disciplining, of ideas, facts, and things in any system of classification and organization, in turn becomes linked to an expert’s, and institution’s, claims to legitimacy (Allan, 2011).

Foucault’s purpose was to then unearth the process of how a field’s objects of study had been created by their practitioners. The social sciences, including criminal anthropology, developed in nineteenth century Europe in the wake of the Enlightenment. The evolving notion of the criminal as a type to be studied through social science also serves as a precursor to sociologist Max Weber’s notion of an “ideal type”: a categorization scheme where key components are always present in an abstract ideal of a social phenomenon, such as a bureaucracy always involving characteristics of efficiency, written rules, merit-based careers, and impartiality (Weber, 1948). Crucially, work in the social sciences should be considered periodized in terms of the social debates and political milieu of a time being inextricably interconnected with what is being researched, how it is being researched, and the conclusions being drawn.

There is no shortage of early work from social scientists with titles and content that confidently reify their subjects and then overgeneralize about the object of their study. Anthropology, for example, first emerged as an imperialist, colonialist science developed by white Europeans to study “primitive” cultures, with works imaginatively constructing an exotic Other through the presumption of researcher objectivity. The cumulative discussion of such characteristics could then be presented through definitive statements on “The ______,” to be discussed and addressed. Any scholarship that today would refer to those under study as “The _______” (as, for example, the Jew, the disabled, the single mother, the homeless, etc.) would likely merit derision and dismissal. I am left wondering what the history of various social science disciplines is regarding when, how, and why such homogenizing phrasing went out of favor, perhaps abandoned (or at least made incredibly marginal in scientific discourse) because it became viewed as essentialist, racist, or for other reasons (see for example my references to the diagrams “Negroid sane criminals and Negroid civil insane, mosaic of metric differences,” undated, and “Forgery and fraud, rankings of native whites of foreign parentage,” undated, each of which was once presented by the American Philosophical Society). Perhaps books and other material presented as scientific with such essentialist, overgeneralizing, racist titles were gradually replaced by newer, more specialized work about specific behaviors and processes, and with greater self-reflexivity and nuance, and devoid of clear racism. Criminal anthropology both helped create and support eugenic agendas (Rafter, 1997), ones once also supported in the U.S. but then (largely) falling out of favor with the rise of Nazism (Conroy, 2017; Rafter, 1997).

The purpose of such practices today, in hindsight, appears to be about creating emerging social science disciplines and their validation of experts as much as about purported explanation. The explanation in The Criminal is rooted in the then-developing figure of expert scientists who themselves are, concurrently, producing a discipline’s institutionalization. The sense of a new science, in the process of its creation, perhaps meant its practitioners were incentivized to present it as fully authoritative, as the most powerful explanatory force then currently available. A scientific analysis of any social topic at the time was designed to set the bar for understanding in the emergent Modern era—what other discourses (besides the fading power of religion) could hope to compete with expertise rooted in science? Such formations all have roots in discourses (like those of the emerging eugenics movement) that were then being presented as self-evidently scientific, all less than one hundred and forty years ago.

To what extent can, or should, an author generalize using any objectifying categorization of a social category as a type? Criminology has a history of trying to balance the reification of a type with the ability to label and understand a phenomenon (with figures like “the serial killer” and “the violent sex offender” being specific and contemporary targets of research, for example). An ongoing question then becomes how does, and should, one present, and use, social science?

Experts are defined as knowing, and being able to use, simplify, and clarify complex information. In another interpretation, perhaps the use of “the criminal” in Ellis’ title is what the author or publishers simply thought of as clear, concise, and marketable phrasing at the time. One can try imagining an alternate and more specific title, like Variations of Criminals and their Characteristics: A Literature Review of Current Research, but such a title doesn't have the same concision and punch.

Even today, the recent replication crisis in science makes it clear that some norms and practices promoted within science (such as presenting results as statistically significant through data mining targeting and p-hacking in single, small studies) can be used by some practitioners to mis-represent their claims as valid, expert knowledge (Piper, 2020). When studies rooted in experiments are published as having novel and statistically significant findings but with results later determined to be unreproducible, they lend support to discourses discrediting science.

Science is practiced by people, and always within a specific culture and era. Ellis’ work was the most prestigious scholarship in his field at the time. The formal and natural sciences are unarguably (and exceptionally) useful, but the application of science toward understanding human culture is inexorably intertwined with a researcher’s subjectivity and creativity. I hope the textual experiment and its individual statements presented here cumulatively illustrate how early scientific work involved frames through which the topics were not simply studied, but created (and, to some extent, still being promoted today). The conceptual writing here helps show the origins of a field like criminology, and how fields grow reified. It presents, in a creative way, an analysis of criminology's foundational assumptions, hiding in plain sight.

Notes

I have excluded Ellis’ use of the phrase “the criminality,” despite it containing the letters ordered in the phrase “the criminal,” and also excluded the phrases “the criminals” or “the criminal’s.” (Such fine points of what exactly is being measured, counted, and/or considered are, of course, central to any operational definition in science. Another author might well use another form of operationalization in their projects.)

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the editor, Professor Ellen Berry, and anonymous reviewers for their insights and guidance. Any errors in this work are, of course, my own responsibility.

References

American Philosophical Society. n.d. “Forgery and fraud, rankings of native whites of foreign parentage.” Diagram in Eugenics Archive. eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/static/images/1247.html

American Philosophical Society. n.d. “Negroid sane criminals and Negroid civil insane, mosaic of metric differences.” Diagram in Eugenics Archive. eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/static/images/1243.html

Conroy, Melvyn. 2017. Nazi Eugenics: Precursors, Policy, Aftermath (Foreword by Tudor Georgescu). Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Dowdy, Eric. 1994. “Federal Funding and its Effects on Criminological Research: Emphasizing Individualistic Explanations for Criminal Behavior.” The American Sociologist 25(4):77-89.

Ellis, Havelock. 1890. The Criminal. New York: Scribner & Welford.

Foucault, Michel. 2003. Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–76. New York: Picador.

Foucault, Michel. 1970. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage.

Green, David. 1984. “Veins of Resemblance: Photography and Eugenics.” The Oxford Art Journal 7(2): 3-16.

Goldsmith, Kenneth. 2008. “Conceptual poetics.” Poetry Foundation. poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/2008/06/conceptual-poetics-kenneth-goldsmith.

Gottfredson, Michael, and Hirschi, Travis. 1987. Positive Criminology. Sage.

Jameson, Frederic. 1975. The Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian Formalism (First Paperback Edition.) Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kuhn, Thomas. 1996. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (3rd ed). University of Chicago Press.

Lombroso, Cesare, and Giną Lombroso Ferrero. 1911. The Criminal Man. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Piper, Kelsey. 2020. “Science has been in a ‘replication crisis’ for a decade. Have we learned anything?” Vox. 14 October. vox.com/future-perfect/21504366/science-replication-crisis-peer-review-statistics.

Rafter, Nicole Hahn. 1997. Creating Born Criminals. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Raine, Adrian. 2013. “Neurocriminology: Inside the Criminal Mind.” Wall Street Journal. 26 April. wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323335404578444682892520530.

Samenow, Stanton. 2014. Inside the Criminal Mind (Revised and Updated Edition.) New York: Crown.

Science. 1890. “Book Reviews: The Criminal. By Havelock Ellis.” Science 15(385): 376-377.

Siegel, Larry. 2017. Criminology: Theories, Patterns, and Typologies. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Stephens, Elizabeth. 2013. “Francis Galton’s Composite Portraits: The Productive Failure of a Scientific Experiment.” Pre-publication version. researchgate.net/publication/323275029_Francis_Galton's_Composite_Portraits_The_Productive_Failure_of_a_Scientific_Experiment.

Weber, Max. 1948. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, Eds.). London: Routledge.

Cite this Essay

Borchard, Kurt. “The criminal in the prison-house of language: Conceptual writing to re-present Havelock Ellis’ use of “the criminal” in his book, The Criminal.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 40, 2024, doi:10.20415/rhiz/040.e02