Utopian Accidents: An Introduction to Retro-Futures

Davin Heckman

In pointing to this postmodern sense of an ending, of living after the future or suspended in a perpetual present, I don't mean to suggest the fundamental illegitimacy of any of the positions characterized above. Postmodern critiques have been vitally necessary and, arguably, socially transformative (at least in their intentions). But I do want to suggest why it has become so difficult for contemporary progressive thinkers to posit the new — in exact inversion of their modernist counterparts and in absolute contradiction to a self-identity as progressive — and, perhaps more importantly, to speculate on some of the consequences arising from this refusal.

—Ellen E. Berry in "Rhizomes, Newness, and the Condition of Our Postmodernity" (Berry and Siegel par. 2).

[1] In "Rhizomes, Newness, and the Condition of Our Postmodernity" (the introduction to Rhizomes 1), Ellen E. Berry and Carol Siegel stirred up in me some questions about newness that have colored my tenure as the journal's technical editor (issues 2 through 6), provoked my dissertation research into the history of the "smart house," and have coalesced here in the pages of Rhizomes 8, my special issue on "Retro-Futures." I cannot pretend that all of the issues preceding this one have not in their own way flouted the shatterproof screens of our imaginary monitors, which let us look for tomorrow, but also prevent us from stepping forward into it. Nor can I pretend that this issue will make your monitor spark and sputter as it gulps you fast forward into the future. In fact, it is times like these, when I blink insatiably and hope that my eyes will stop burning, that I am tempted to destroy my monitor in a sputtering and sparking marriage of lukewarm coffee and high technology — a toast to cybernetics. I think, on a spring day like today, the future is outside. But because I have work to do, I will have to put this fantasy off until tomorrow.

[2] The idea for a "Retro-Futures" issue, in part a gift from Ellen Berry and Carol Siegel and inspired by the difficulty in imagining newness, was a natural extension of my own fascination with shifting conceptions of the future as encountered vis-à-vis my own research into household technologies. In my own work, three questions bubbled up to the top of my research priorities: Why was the future of the 1950s and 1960s as embodied in design so fanciful? Why do contemporary trends in design so often embody neo-traditional and/or "retro" aesthetics? And why do the radical futures of the past seem so naïve, while the stale futures of today seem so sensible? In looking for possible answers to these three questions, more general questions about culture and temporality emerged: What did the future mean in the past? What will the past mean in the future? And what do these concerns mean for us right now? The result of these queries is this exciting point of departure — a special issue of Rhizomes.

[3] To respond to Berry and Siegel's provocative introduction with yet another introduction, I'd like to focus my portion of this issue on this question of culture and temporality, but add to it an element which I feel will be a defining but sometimes invisible theme running through many of the contributions to this issue: technics. Technics is used here to describe a general worldview and its manifestation in ethical terms which brings about technological answers to problems of labor, economics, health, and the social. Technics, then, refers to the milieu which gives rise to technology, its practices or techniques, and its human counterpart, the technician. In the context of modern (and postmodern) societies, technics is the means by which the futuristic is mobilized and notions of progress are registered.

[4] The case-study which I will use to map out technical shifts in temporal modalities is a futurism with which many are acquainted: Disney's model of utopian living [1]. The most radical example of this futurism is Walt Disney's original planned community, the unfulfilled dream of EPCOT. This example is followed by a more moderate version, the EPCOT Center theme park. And finally, this futurism reaches an appropriate end in Disney's city, Celebration, Florida. The goal of this case-study is to gain a greater understanding of how these futurisms resonate with cultural ideals and economic practices. Ultimately, I hope to account for the crisis of imagination, and in doing so, suggest a world that exists outside of managed innovations and preempted serendipity.

I. Introducing Change — Epcot One.

[5] Conceived in the 1960s, Walt Disney's Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, or EPCOT, was to be both a laboratory for future technology and a home for the citizens of tomorrow. The origins of Walt Disney's city can be traced through the "World of Tomorrow" World's Fair held in New York in 1939-40. Among many notable attractions listed in The Official Guide Book of the New York World's Fair 1939, General Motors' "Highways and Horizons Exhibit," which featured Norman Bel Geddes' "Futurama" highway of tomorrow ride (consisting of "magic chairs" that moved spectators around what was then the largest scale model in the history of the world), is among the most widely referenced precursors to what would become suburban America (207-08). A transcript of the "Futurama" narration reads prophetically, as spectators were treated to a view of a model of what looks remarkably like a contemporary concrete superhighway (without the potholes, accidents, and litter):

Looming ahead is a 1960 Motorway intersection. By means of ramped loops, cars may make right and left turns at rates of speed up to 50 miles per hour. The turning-off lanes are elevated and depressed. There is no interference from the straight ahead traffic in the higher speed lanes. (Zim et al. 109)

According to Helen Burgess, in her article "Futurama, Autogeddon," the General Motors exhibition was prophetic in other ways as well:

In a montage of stock images, the film announced the coming of the world of tomorrow by tapping into narratives of progress and manifest destiny. The film then went on to showcase the Futurama model exhibit, showing close-ups of the Futurama diorama in action, and ended with shots of the popular exhibition building itself, replacing the familiar "the end" with "Without End" to signifying that the future was something to strive for indefinitely. (3)

Beyond simply proposing a future of automobiles and superhighways, the General Motors exhibit emphasized a way being that would be more clearly realized as consumers approached the 1960 of Bel Geddes' future.

[6] A more recent precursor of the smart home can be found in the 1964 World's Fair, also held in New York, for which WED created attractions for Ford Motors ("Magic Skyway"), Pepsi-Cola ("It's a Small World"), General Electric ("Progressland"), and the State of Illinois ("Great Moments With Mr. Lincoln") — all of which were among the most popular attractions that year (Thomas 313). What is significant about EPCOT, however, is that it takes these attractions a step further, and imagines them as parts of an integrated living environment — in EPCOT, actual families would live, work, and play in a technologically rich environment. In a promotional film released in October 1966 [2], Walt Disney describes this idealized relationship between the corporation and the individual, "when EPCOT has become a reality and we find the need for technology that don't (sic) even exist today, it's our hope that EPCOT will stimulate American industry to develop new solutions that will meet the needs of people expressed right here in this experimental community." In keeping with the spirit of his times, he imagined that the vast resources and engineering capabilities of corporate America that had provided the middle class with such abundance and prosperity in the 1950s could be called upon to take this technological manifest destiny a step further, solving problems that have yet to be imagined. Walt continues, enthusiastically, "It will never cease to be a living blueprint of the future where people actually live a life they can't find anyplace else in the world." On another occasion, he explained, "It's like the city of tomorrow ought to be, a city that caters to people as a service function" (qtd. in Thomas 349). Even more revolutionary (or prophetic), this city of the future would have no landowners (except, presumably, at the corporate level), no voting controls, and no retirement; all citizens would be required to work for the maintenance of the city and would live in rented houses and apartments (Thomas 349). EPCOT, as envisioned by Walt Disney, would be the second coming of the American dream, redirecting the frontier myth into consumer practices, and speaking to all peoples of a place beyond prosperity, beyond freedom, and beyond the mundane imaginings of ordinary life. In short, EPCOT was to be the future — a spectacular vision of an American utopia institutionalized as a process of constant becoming.

[7] Unlike past utopias, which yearned for a state of completeness, this one would achieve perfection in the process of change. Like the latest software, EPCOT would be perfectible insofar as it is upgradeable, and its sophistication would lie in its ability to be rewritten. An early manifestation of contemporary corporate strategies which seek to manage innovation as a resource which can be directed to produce continued results, the idea of an institutionally regulated revolution may seem paradoxical at first, but when considered alongside the reputable business practices of insurance, real estate speculation, money-lending, and stock trading, this attempt to negotiate "risk" makes a great deal of sense. It seems that as long as technological development is a capitalist enterprise, there will continue to be economic benefits for companies which can subdue the chaos of radical innovations by channeling change through the matrix of existing infrastructures.

[8] This goal of "becoming," which is temporally different from "being," positions subjectivity in advance of the present, or as a movement to an ever moving destination. Traditionally understood (or misunderstood) under modernism through concepts such as the "avant-garde" or, in more mundane terms, through the experience of daily life as a succession of novelties, the tension between "chance" and "contingency" has been brought about by efforts to intermingle human subjectivity and the time of the industrial world. As Mary Anne Doane explains in The Emergence of Cinematic Time:

In the face of the abstraction of time, its transformation into the discrete, the measurable, the locus of value, chance and the contingent are assigned an important ideological role — they become the highly cathected sites of both pleasure and anxiety. Contingency appears to offer a vast reservoir of freedom and free play, irreducible to the systematic structuring of "leisure time." What is critical is the production of contingency and ephemerality as graspable, representable, but nevertheless antisystematic. It is the argument of this book that the rationalization of time characterizing industrialization and the expansion of capitalism was accompanied by a structuring of contingency and temporality through emerging technologies of representation — a structuring that attempted to ensure their residence outside structure, to make tolerable an incessant rationalization. (11)

The seemingly disparate relationship between avant-garde aesthetics and increased rationalization is understood as an attempt to find aesthetic pleasures in the impartial epistemologies of modernism. Where rationalization produces a system of order that is unconcerned with subjective relationships, representation attempts to incorporate the experience of industrial life into subjectivity.

[9] To draw a comparison, seasonal time for an agrarian society is experienced not only as necessary for the continuation of agricultural sustenance, but as part of religious, cultural, and imaginary time. This integrated subjective experience is a part of what Vilem Flusser calls the "magical" world, which he describes in Towards a Philosophy of Photography:

This space and time peculiar to the image is none other than the world of magic, a world in which everything is repeated and in which everything participates in a significant context. Such a world is structurally different from that of the linear world of history in which nothing is repeated and in which everything has causes and will have consequences. For example: In the historical world, sunrise is the cause of the cock's crowing; in the magical one, sunrise signifies crowing and crowing signifies sunrise. (9)

This example is significant because it highlights the technical relationship between different subjective experiences. For an order which is typically construed as a superstitious one, causality does not flow neatly from one thing to another largely because the various forces in operation are those upon which the subject depends. In the case of the cock's crowing, for the peasant farmer, it is unimportant which comes first, because both the cock's crowing and the sun's light are the indivisible parts of one's being. But because science is a result of experiments and trials, the question of causality is crucial to the development of new knowledge. And technology, because it purports to offer improvements on existing ways of doing things, must insert itself into a system [3]. Hence an awareness of organization and a model of linear causality emerges to replace the system of magical correspondences. Progress requires an ability to isolate causes and insert new causes that produce better effects.

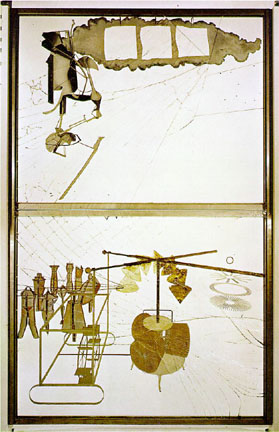

Figure 1: Marcel Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Large Glass) (1915-1923).

[10] Because, as Doane argues, modernism produces a system of ordered living, modernist aesthetics must offer subjective freedom through resistance by way of contingency. However, another effect of rationality is that it can, in the pursuit of causal relationships, subvert the subjective chain of causality which Flusser attributes to the magical. In other words, the abstraction of life that clock time produces is one which is, as modern art suggests, antithetical to subjective continuity and holism. To use the example of artisanship versus factory labor: For the artisan making a toy, making-a-toy is a process from start to finish in which one sees a creation emerge from raw materials; for the worker, making-a-toy is scattered and dispersed across several workers laboring over several specific stages of the product's completion. The chain of causality and order is more abstract because one does not start or finish doing anything but making a particular part. From a utilitarian perspective, an assembly line might make more "sense," but from another angle, the sense one must have in order to make meaning of this work requires an abstract notion that one is "building" something collectively. Similarly, the cures offered by medical science or behavioral specialists do not necessarily have an apparent link with the pathology which they attempt to remedy. Modernist art, in this context, might be understood as an attempt to create a subjective picture of this new experience of causality. As in Marcel Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Large Glass) (1915-1923), the social situation is cast in abstract terms as a relation of mechanical parts that function in harmony to reproduce a social interaction. Although The Bride Stripped Bare might seem a bit "nonsensical," it is an attempt to produce a subjective experience of a new system of order.

[11] To return to the discussion of EPCOT, this cultural orientation which situates being outside of the ordinary, while certainly a staple of any society undergoing social change, suggests the following: On the one hand, the coherent nature of the Enlightenment self and the conceptual purity of High Modernist architecture are present in Disney's plan. On the other hand, this plan can account for the incoherencies of a changing self and the instability of a changing city. While Doane's discussion of modernism points to the role that contingency and chance play in the realization of freedom amidst the organizing forces of modernist rationality, more recent industrial developments (like just-in-time production, flexible accumulation, and pay-per-use) seem to be a reacting to contingency itself. Where modernist aesthetics intended to produce freedom, industry finds an asset in abstracted social relations. As an expression of "cinematic time," which "acknowledges contingency and indeterminacy while at the same time offering the law of their regularity" (Doane 31), more recent mainstream cinematic displays seem to accept the contingent nature of representation, yet adhere to a relatively stable system of narration [4]. Taken as a "regular" part of subjective experience, rationalized systems must take into account this regular irregularity as an area of knowledge. And in a society which traffics in cultural commodities such as film, television, fashion, and advertisement, entrepreneurs must inevitably industrialize these spaces as well. Thus, the goal of EPCOT was to rationalize fluidity, to traffic in what has been often called "postmodernity" as part of an ordered strategy for social progress.

II. Managing Change — EPCOT Center to Celebration, Florida.

[12] For all of its visionary promise and utopian dazzle, Walt Disney's plans for EPCOT were shelved after his death a mere two months after he released his plans for the community, and the company's efforts, under the direction of his brother Roy Disney, were turned towards the more profitable end of providing entertainment. It was in the name of entertainment that EPCOT was eventually resurrected, and finally built in the early 1980s as the EPCOT center theme-park, a tourist destination and companion to the Magic Kingdom at Disney World in Florida. The updated corporate position on the EPCOT Center is expressed in an article in the futurist-oriented OMNI magazine, published in September, 1982: "The EPCOT that will open this fall will have no permanent residents. The company has adopted the line that the tens of thousands of daily visitors to the Florida Disney complex will be its residents" (Osonko 70). And, although the article cites Walt Disney's enthusiastic rhetoric, reminding readers that EPCOT "will always be in a state of becoming" (Osonko 70), one reader felt the need to express his dismay in a letter published in the following February. In his letter to the editor, Jerome Glenn writes, "When I found out that EPCOT would not have residents, I was furious at WED Enterprises for not honoring Walt's wish" (10). EPCOT had shifted from being a utopian community forged out of a union between big business and the common citizen, the rationalized embodiment of planning in a technological society, to a theme park in a society that has increasingly found its utopian promise in entertainment and media. Rightfully ruffling the futuristic feathers of at least one reader, EPCOT had ceased to be a place where the future was to be sought as a process of becoming and had been replaced by a series of attractions through which new products could be observed. The early plan for EPCOT had been scrapped to make way for a more limited and more resolutely commercialistic actuality. The transformation is a profound one, which reverberates through the discourses of household technologies that will be analyzed at length in later chapters. With this transformation of Walt Disney's plan in the 1980s, the whole project of "becoming" is understandably watered-down and diminished in its affective flavor. Sure, the current EPCOT traffics in some of the familiar futurist tropes, but in this case, loses a little bit of its romance (even if it still maintains its intensity). The new EPCOT, as a theme park, is a vehicle for consumption and, as such, the subjective agency it offers to its audience is no longer the becoming that comes through living in the future, but the actualization that comes through consumer practices and the enjoyment of entertainment. To return to the idea of managed innovation, the original plan for EPCOT and its eventual form might not be all that divergent, since both are attempts to provide rationalization to order — what John Hannigan has called the "riskless risk" [5].

[13] Although formally and nominally EPCOT had already been built in the 1980s, Walt Disney's utopian rhetoric of 1966 gets dusted off and used once again in the 1990s; this time, to promote the creation of Celebration, Florida. Established in 1994, Celebration is a planned residential community, just outside of Orlando, near the Walt Disney World resort and theme park. Tapping into "The New Urbanism" movement, which was officially named in 1990 and generated a professional organization (the Congress for the New Urbanism) in 1993 (Fulton 10), Celebration would make use of "neotraditional," pedestrian-friendly planning and would provide a nostalgic feel through "six traditional design styles," "small neighborhood parks," and "ample public spaces" (25) [6]. Focusing on the qualities that made pre-World War II middle class neighborhoods colorful, interesting, and dynamic, New Urbanist cities like Celebration are an attempt to turn away from sprawling, automobile-centered suburbs, and the social and civic isolation that they produced.

[14] However, Celebration goes beyond architectural styles and geographical layouts to satisfy its residents. According to the city's official website, Celebration is "A place where memories of a lifetime are made, it's more than a home; it's a community rich with old-fashioned appeal and an eye on the future" (Celebration). As the slick nostalgia of the promotional materials betray, Celebration is all Disney. Its teary-eyed nostalgic glance at small town American life places it securely in the tradition of Disneyland's Main Street, U.S.A. Its rigorously planned aesthetics and scrupulously scrubbed surfaces give it all the flair of Disney's feature animation. And the fact that it houses actual residents while providing them with the up-do-date technology suggests at least a nod to the more wide-eyed visions of Walt Disney himself. Celebration, as a result, is situated in the context of Walt Disney's dream and the corporation's agenda, and represents a powerful manifestation of utopian thinking in the contemporary setting. Although radically different in appearance from both versions of EPCOT, Celebration is perhaps the most sophisticated and innovative effort to advance the technology of innovation management that had been pioneered by its predecessors.

[15] While many people point to the obvious claim that Celebration represents a more conservative vision of the idealized place than EPCOT, I think it is wrong to describe it as merely reactionary. Douglas Frantz and Catherine Collins make this mistake, explaining,

where Epcot looked to the future, Celebration turned to the past. Where Epcot was a vision of the direction in which the American city might be headed, Celebration represented the country's disenchantment with the metropolis and its new embracing of the town of decades past. (28)

The homes at Celebration, significantly, are wired homes. Each one is provided with access to "e-mail, chat rooms, a bulletin board service, and access to the Internet, all free of charge" (Frantz and Collins 148). In addition, the town itself has been sold by its appeal to the narrative of a "perfect day" — and all aspects of the community are built with this in mind [7]. Similar to a theme park, the goal of Celebration is to construct the home as "the happiest place on earth."

[16] The neo-traditional homes in Celebration reflect a larger narrative about lifestyle in which traditional themes and stylings are combined with technologies of information and media. This ambiguous use of "smart" to describe both high and low-tech "solutions" is echoed by Votolato, who notes:

The chic designs of the avant-garde and the homes of ordinary people are composed of the found and the fabricated, inventive combinations of old and new materials, of high technology and low technology (cottage-computer work), of the advanced and the archaic, of the rational and the romantic and, on the Internet, of the public and the personal (156).

Rather than creating homes that would complete tasks effortlessly or generate a spectacle around futuristic living, the contemporary smart home is based more securely in the consumption of media. The spectacle is not the home itself, as much as the information that circulates through the home. Related to Martha Stewart's do-it-yourself homemaking, which fixes not the problem of material scarcity, but presents solutions to questions of style through easy-to-follow instructions by which consumers, led by a corporation, can purchase the tools needed to achieve a refined and fashionable American domesticity ala Catherine Beecher. Not simply about labor, relaxation, ease, amusement, or spectacle, such homes are a constellation of ideas and technologies which exist to generate and control the imagination, and manage the refined way of being called a lifestyle. The contemporary smart home is a technical network constructed to make every day "the Perfect Day."

[17] An excellent example of this astute sense of negotiation between being and becoming is dramatically acted out in Henry Ford's prototype of postmodern history, Greenfield Village. Using his fortune to purchase historic sites of invention (like Edison's Menlo Park laboratory and the Wright Brothers' bicycle shop, for example), Ford constructed an entire village comprised of historic buildings just outside of Detroit, Michigan. A tribute to American inventors and industrialists, Greenfield Village was called by Ford himself, "a synthesis of the home-spun and the high-tech" (qtd. in Votolato 75). The village presents itself like a strange combination of Disney's Main Street and Knott's Berry Farm's Ghost Town, an eclectic mix of buildings that conjure up images of an America steeped in nostalgia, even as the nostalgia it conjures up is that of invention and industrial advancement. Greenfield Village uses the past to create a history as movement into the future, making it a profound attempt to reconcile the tension between being and becoming by establishing the process of becoming into the notion of historic nationalism — American technological exceptionalism yoked to Manifest Destiny [8].

[18] This negotiated introduction of gadgets into the space of the traditional home is also an understood aspect of the history of design, as evidenced in the following passage:

The domestic kitchen became one of the greatest arenas of this contest. With high-tech, Sub-Zero refrigerators and glossy Kitchen Aid dishwashers standing proudly between Colonial or Shaker cabinetry, American kitchens reconciled the personal need for emotional comfort with the high technological expectations of the modern family. (Votolato 4)

Like Henry Ford's "historic" village, Disneyland's Main Street, the Bonaventure Hotel, a taxicab in Tegucigalpa, or glitzy Las Vegas itself, the space of the home during a period of technical transition during the age of mass media is full of paradox or, dare I say, postmodern stylistic elements.

[19] The shift in design narratives from becoming to being is nowhere more evident than in the shift from EPCOT to Celebration. Celebration, the town in Florida built and planned by the Disney Company as a social experiment, deviates from EPCOT in significant ways. Celebration's architecture rejects the "futurist" stylings of the original EPCOT (which was to be a domed city, complete with monorails and vacuum-powered centralized waste disposal among other things), in favor of a more conservative look akin to "Small Town America." Neighborhoods are residential with green lawns, large front porches, and "quaint" homes. The aesthetic of Celebration is captured in this early, but unused, draft of the town's "backstory":

There was once a place where neighbors greeted neighbors in the quiet of summer twilight. Where children chased fireflies. And porch swings provided easy refuge from the cares of the day. The movie house showed cartoons on Saturday. The grocery store delivered. And there was one teacher who always knew you had that special something. Remember that place? Perhaps from your childhood? Or maybe just from stories. It had a magic all its own. The special magic of an American home town. (qtd in Frantz and Collins 23)

The slick advertising rhetoric constructs Celebration as a small town, drawing on Disney's long tradition of creating and conjuring peaceful and pleasurable "memories" for "children of all ages."

[20] The tension between being and becoming thus accounts for shifts in the narratives used to market smart homes to subjects. In The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord provides a useful tool in the term "spectacle," as the source of alienation in consumer society:

The alienation of the spectator to the profit of the contemplated object (which is the result of his own unconscious activity) is expressed in the following way: the more he contemplates the less he lives; the more he accepts recognizing himself in the dominant images of need, the less he understands his own existence and his own desires. The externality of the spectacle in relation to the active man appears in the fact that his own gestures are no longer his but those of another who represents them to him. (par. 30)

The term "spectacle" is used loosely, to describe a power technique of which mass media are merely the most obvious example. For Debord, one of the many problems with the spectacle is that its method of production, which is consumption, offers itself up to consumers as an illusion of social unity — spectators become part of a community that shares in the common fixation, and the images consumed tell stories of satisfaction. Entertainment, for example, requires one to spend more time focusing on this illusion of unity, rather than in the pursuit of social pleasures. This is also true for other commodities — toothpastes promise new plateaus in whiteness, automobiles promise style and perfect utility, paper towels promise revolutionary levels of absorbency — all of which, by the way, can result in improved social opportunities, deeply satisfied interior states, and better lives. As a result, the more satisfaction one seeks via the spectacle, the more reinforced the feelings of dissatisfaction one suffers when removed from the spectacle. The benefit that these products offer, aside from their practical utility, is in their ability to communicate ideas that embody power in their symbolic value. It is this social power that is described by way of Bourdieu's discussion of "cultural capital." And it is when this power is removed from the spectacle, debunked, and divested of its claims to grandiosity, that one feels disenchanted, isolated, and alone.

[21] Insofar as the spectacle calls us to participate in a fantasy that is eternally before our eyes, yet eludes our grasp, there is the constant potential for alienation. In terms of consumer practices, this then places products in a double bind: to fuel constantly growing market shares, they must both inspire consumer confidence by delivering some sense of satisfaction, yet they must also ensure the constant need for consumption. Thus Celebration relies on a process of mediation between the old and the new, a syncretism which celebrates the comfort of the ordinary and the promise of extraordinary comforts.

III. Conclusion — Consuming Technics.

[22] The fact that history recirculates and reproduces in the present references to past styles and motifs has come to be a standard theoretical point for those versed in postmodernism. To quote Jameson on this key feature of the postmodern,

This situation evidently determines what the architecture historians call, "historicism," namely the random cannibalization of all the styles of the past, the play of random stylistic allusion, and in general what Henri Lefebvre has called the increasing primacy of the "neo." (18)

This tendency to fall back into past styles, often nostalgically, might provoke superficial critics to read the situation as reactionary and conservative [9]. However, for a society which has clearly embraced unprecedented technological changes which have made themselves felt in all other areas (social, scientific, ethical, spiritual, economic, political), is it inconceivable that the reincarnation of the past is not itself a manifestation of the new?

[23] The technical system has established itself through hegemonic means, employing both positive and negative methods to secure its normative and central role in culture. Through futurist marketing strategies, new technology is made to appeal to that slim, but important, sector of the market called "early adopters" which are eager to use new technologies by virtue of their newness. The vast majority, however, are interested in products whose design is governed by the blatantly hegemonic principle "MAYA" or "Most Advanced Yet Acceptable" (Votolato 121). This large middle segment of the population will adopt technologies that seem to mediate between the new and the old, the emergent versus the dominant. The adoption of new technologies very clearly illustrates Gramsci's notion of hegemony in detail, consisting of a large and normal "middle" flanked by marginal elements who are both "progressive" and "reactionary," negotiating the advance of cultural norms through a process of give and take — the crucial difference, however, is that this form of cultural coercion, it would seem, is more clearly tailored to technical advancement than traditional Marxist economic models. In this context, the history of managed innovation in the twentieth century, although tied to economics, is clearly geared towards the promotion of technological advancement at any cost.

[24] Contrary to those postmodernists who might argue that we are seeing an absence of organization and a total rejection of modernism, Bernard Stiegler puts forward the possibility that we are, in fact, becoming more organized than ever before (albeit, through inorganic means). The reality of the technical system, for Stiegler, is described in the following passage:

The evolution of technical systems moves toward the complexity and progressive solidarity of the combined elements. "The internal connections that assure the life of these technical systems are more and more numerous as we advance in time, as techniques become more and more complex." This globalization [mondialisation] of such dependencies — their universalization and, in this sense, the deterritorialization of technics leads to what Heidegger calls Gestell: planetary industrial technics — the systematic and global exploitation of resources, which implies a worldwide economic, political, cultural, social, and military interdependence. (31)

Stiegler's definition of technics, a generalized system of interrelated parts pragmatically pushed forward with little regard to "theoretical formalism" (34), is the most clear articulation of current sociotechnological trends. With the human scale of language, nation, and memory being rent asunder by the machinic forces of integration, for once the technical system does not require our theoretical conception of organization, and thus organizes even the smallest facets of our lives according to its practical needs. The current trend is merely a continuation of Frederick Taylor's call to parse things up into ever smaller and more manageable bits. This gruesome possibility is especially evident in the cruel illogic of globalization which pays no respect to mind or body and defiantly forces all into its unintelligible system of order [10].

[25] Under this new world order, the political project is one of memory: "This politics would be nothing but a thinking of technics (of the unthought, of the immemorial) that would take into consideration the reflexivity informing every orthothetic form insofar as it does nothing but call for reflection on the originary de-fault of origin however incommensurable such a reflexivity is (since it is nonsubjective)" (276). The challenge is not simply to get used to always becoming more technological, but to remember that we are human by engaging in the constant philosophical project of framing the world in the context of human experience (which is a technical project). In simpler terms, Stiegler is suggesting that people, in the face of virtuality, ought to remember that technics, from time immemorial, is not everything. In fact, it is our lack.

[26] The problem of newness is not one of simply not having anything new, nor is it a lack of belief in the new. Instead, it should be seen as embedded in a larger technical issue which has to do with the commodification and management of knowledge. The attempt to account for changes is part of the logic of our current economic phase. We economize risk in the management of the future and refuse to admit ruptures by factoring them into projections in an attempt to guide the future down the path of the predictable. Under this belief system, pseudo-newness is presented as a gimmick, while actual newness is experienced as a disaster or failure of the technical system. The improbable actuality is called an accident [11].

[27] The "accident" inserts itself into our programmed lives as an interruption of the transmission, as the unintended consequence. But a deeper consideration of the term, as that which is not essential, captures the essence of what makes humans such elaborately constructed creatures and thus betrays the negative connotations of this term. Human beings are distinguished from other creatures by the excessive nature of our existence — we employ our "free will" when we manage to exceed the parameters of our programming. Consumer-driven technical rationalities and their consequent attempts to contain risk should be seen, not as profound examples of human achievement, rather they should be seen (alongside death camps, prisons, ghettos, and war zones) as instruments by which we neutralize our "accidental" natures.

[28] Current wisdom seems to dictate that open-ended and incomplete solutions which leave space open for the arrangement of future solutions is the surest way to see that progress can be made pragmatically and predictably. However, it is also possible that these open architectures, while allowing for limited development along a particular trajectory, can only develop insofar as their particular line of development has been anticipated. In other words, planning for innovations might more effectively seal off lines of flight, not with walls, but with reservoirs and release valves by diverting energetic breaks towards the completion of already established trajectories. Because tomorrow, in the current context, has already been accounted for and mediated by what are ultimately risk-moderating mechanisms which make the future a relatively stable market for speculation; the avant-garde no longer exists. As disappointingly portrayed in the conclusion of the Matrix trilogy, innovation serves as a mechanism by which power can continue. The trilogy begins with the exciting promise that Neo will change the world, but ends as he sacrifices himself so that the system, along with the hegemonic illusions of neoliberal globalization, can continue to exist and harvest the energies of the sleeping masses. Without the subjective experience of certainty and earth-shaking effects that fly in the face of certainties, the new is only a minor distraction.

[29] Instead of submitting to the increasingly sterile "reality" of our own making, newness demands an embrace of the fecundity of human life. Rather than attempting to bottle up our dreaded accidents in compliance with the demands of consumer utopia, the cultivation of a "new" revolutionary consciousness requires a healthy respect and appreciation for those things which interrupt the lethargic stability required of docile subjects and the insulting agency awarded to corporate creations and industrial practices. As might be expected, this goal is difficult to obtain in the context of institutional learning, with its increasingly pragmatic and planned courses of vocational study, the regulation of future productivity through high student debt, the administrative move towards business models, the exploitation of graduate students and adjunct instructors, and the increasing "careerism" amongst faculty who find themselves caught up in a sea of growing professional demands. As in other industries, the introduction of risks and perturbations into the system is registered as an accident which threatens the staid and managed system of production.

[30] Fortunately, people still exist in abundance, and thus there is still time to roll back the clock. While some of us might be stuck, marching in lockstep to the beat of salaries and prestige, there are still too many millions — sick, imprisoned, dispossessed, disenfranchised, dying, alone, and forgotten — who might be willing to trade away some of their instability for some of our security. And, perhaps, in the process of this exchange, we might remember what it was like to actually be human — not as an intellectual exercise or cultural safari, but as a transformation. We might get comfortable with risks. We might learn to be perturbed. Most importantly, we might become accountable to the sleeping old man we step around when we take a walk through the city at night, the ruddy-faced woman who constantly mutters menacing words as she paces the streets for endless hours, the filthy child who sits and rocks with his face buried in a jar of glue, the man who itches his scabbed arms and insists that he needs a dollar because he's "hungry," or the last remaining member of a family who is digging for the children that are buried under a pile of American-made rubble. Arm in arm, we can live and die in resistance to the morbid profiteering of our future.

Bibliography

Berry, Ellen, and Carol Siegel. "Rhizomes, Newness, and the Condition of Our Postmodernity: An Editorial and a Dialogue." Rhizomes 1 (Spring 2000): n.pag. 16 March 2004 «http://www.rhizomes.net/issue1/rhizopods/newness1.html».

Burgess, Helen. "Futurama, Autogeddon: Imagining the Superhighway from Bel Geddes to Ballard." Rhizomes 8 (Spring 2004): n.pag. 16 March 2004. «http://www.rhizomes.net/issue8/futurama/index.html».

Celebration Florida, The Official Website. n.d. Disney. 16 November 2003 «http://www.celebrationfl.com/».

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. 1967. Trans. Black & Red. n.p.: Nothingness.org, 1994. 16 March 2004 «http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/pub_contents/4».

Disney, Walt. "Walt's Last Film." 1966. Waltopia: Walt's EPCOT. 2004. Waltopia.com 16 March 2004 «http://www.waltopia.com».

Doane, Mary Ann. The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, The Archive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Duchamp, Marcel. The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Large Glass). 1915-1923. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Audio Recordings of Great Works of Art. 1997. 12 January 2004 «http://www.auralaura.com/bridestripped.html».

Flusser, Vilem. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Trans. Anthony Matthews. London: Reaktion, 2000.

Frantz, Douglas, and Catherine Collins. Celebration, U.S.A.: Living in Disney's Brave New Town. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1999.

Fulton, William. The New Urbanism: Hope or Hype for American Communities? Cambridge; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 1996.

Glenn, Jerome. "Disney Dreams" letter to the editor. OMNI Feb. 1983: 10.

Hannigan, John. Fantasy City: Pleasure and Profit in the Postmodern Metropolis. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Jackson, Peter, dir. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Perf. Ian McKellen and Elijah Wood. New Line Cinema, 2001.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1991.

The Official Guide Book of the New York World's Fair The World of Tomorrow 1939. New York: Exposition Publications, Inc., 1939.

Osonko, Tim. "Tomorrow Lands." OMNI Sept 1982: 68-72, 106-07.

Spielberg, Steven, dir. Jurassic Park. Perf. Sam Neill and Laura Dern. Amblin Entertainment, 1993.

Stiegler, Bernard. Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus. Trans. Richard Beardsworth and George Collins. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Thomas, Bob. Walt Disney: An American Original. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976.

Virilio, Paul, and Sylvere Lotringer. Crepuscular Dawn. Trans. Mike Taormina. Los Angeles: Simiotext(e), 2002.

Votolato, Gregory. American Design in the Twentieth Century: Personality and Performance. New York: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Wachowski, Andy, and Larry Wachowski, dirs. The Matrix. Perf. Keanu Reeves and Laurence Fishburne. Warner Brothers, 1999.

—. The Matrix Reloaded. Perf. Keanu Reeves and Laurence Fishburne. Warner Brothers, 2003.

—. The Matrix Revolutions. Perf. Keanu Reeves and Laurence Fishburne. Warner Brothers, 2003.

Walt Disney Company. "History." The Walt Disney Company Fact Book 2002. 2002. The Walt Disney Company. 16 March 2004 «http://disney.go.com/corporate/investors/financials/factbook/2002/index.html».

Zim, Larry, et al. The World of Tomorrow: The 1939 New York World's Fair. New York: Harper and Row, 1988.

Notes

[1] Throughout this text I will be referring to a number of Disney-related entities. To refer to Walt Disney himself, I will use Walt Disney (sometimes simply Walt for the sake of variety). When referring to the publicly-owned Walt Disney Productions, which became the Walt Disney Company in 1986, I use the Disney Company. At times I will also refer to WED (Walter Elias Disney) Enterprises, which was originally a private company called Walt Disney Incorporated started by Walt Disney in 1952 for the creation of Disneyland, but was sold along with the Imagineers to Walt Disney Productions in 1965. Finally, I will use the term Disney when I need a term to describe the culture of Disney, which is often difficult to distinguish from the imagination of the man and the company which bears his namesake. I will also make occasional use of the ambiguous term when origins, as in the case of EPCOT, are difficult to attribute to either the man or the company. Information on The Disney Company's history is available in the "History" section of The Walt Disney Company Fact Book 2002 «http://disney.go.com/corporate/investors/financials/factbook/2002/index.html».

[2] This twenty-four minute film, which was recorded shortly before Walt's death, is available for viewing on the Waltopia website «http://www.waltopia.com».

[3] Perhaps the reason that technology never simply improves an existing way, but offers new ways of doing things and also new things, might have to do with the loss of a "magical" world view.

[4] The films Jurassic Park (1993), The Matrix (1999), The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), all make great use of effects to construct narratives about places outside of time (prehistoric creatures in the present, a history parallel to our own, and an ancient world before human history, respectively), yet they proceed by way of stable, ordered, and conventional narrative techniques. While they certainly represent radically different possible realities, they do so in a way that is easy to assimilate. The goal of digital effects is to fool the eye and present these fantastic images as coherent and convincing illusions.

[5] The "riskless risk" is a critical term used by Russel Nye, and employed by John Hannigan to describe the function of entertainment in the postmodern city. As Hannigan argues, the object of Urban Entertainment Destinations, the quintessential consumer environment, is to provide intense experiences safe from the threat of harm-a riskless risk (71-74). For a more detailed discussion of this concept, read John Hannigan, Fantasy City: Pleasure and Profit in the Postmodern Metropolis (1999).

[6] According to William Fulton's The New Urbanism, a 1996 report for the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, New Urbanism has been traced back to the late 1970s and early 1980s. Notable contributions to New Urban planning are Seaside Florida, designed in 1981-82 (Fulton 11), Laguna West, California in 1988 (13), and, of course, Celebration, Florida (25). New Urbanism is considered a part of a greater tradition reaching all the way back through the American Garden City movement (1920s-1930s), through the City Beautiful movement (1890-1920s), to Frederick Law Olmsted's 1858 plan for Central Park in New York City (Fulton 7-10).

[7] As Frantz and Collins explain when they describe the ways in which the community is constructed to optimize the everyday, "The design of the community, from the physical structure to the intangible attitudes of its residents, pushes people to confront life around them" (315).

[8] General Motors also provides an interesting example of this tension in the marketing of two of their cars. In the same year (1950), Oldsmobile marketed a "Futuramic" car with a "rocket" under the hood, while Pontiac made an appeal to more traditionally-minded buyers with its "Chieftain," yet both were made by GM and "shared bodies, mechanical components, and advertising agencies" (Votolato 107). The fact that the futuristic car and the nostalgic car were one in the same illustrates the fact that even at this early stage marketers were savvy of this struggle between being and becoming and sought to play both sides in their hegemonic attempt to secure the place of the automobile in everyday life.

[9] Certainly, this has been the case with President George W. Bush, which the left has generally considered to be reactionary, regressive, and "out of step" with contemporary values and the current geopolitical landscape. Bush's strategic use of ideas like "family values" and the frontier myth, taken alongside his plain-spoken manner, could be taken to suggest that he is "reactionary," or against progress. But when one considers the facts that he went to Yale, is the son of a former president and director of the CIA, has spent much of his adult life stewing in the corporate world, and has risen to ascendancy through millions of dollars in donations and the best aides that money can buy; the fantasy that he is a mere country bumpkin, elected president in spite of his poor academic performance and public speaking skills, should be recognized as inaccurate. The fact of the matter is that neither Bush nor his Neoconservative advisors really want an America that is trapped in the past. Instead, they imagine a new era of unchallenged military, technological, ideological and economic world domination. The future they imagine, and are working towards, is truly unprecedented; and because of this, the various public relations ploys and ideological motifs they cloak themselves in ought not be considered as some simple archaicism.

[10] Taken in the context of the intellectual, the model of the posthuman as neo-savage offers a particularly interesting by-product of technical advancement. As a citizen in the age of globalization, the posthuman affords contemporary anthropologists a model of the other that is mysterious and unknowable, but also "fair game" and incorruptible in the sense that this model immediately eschews categorization and interpretation. Protected by expertise, scholars are free to adopt virtually any pose with impunity as cultural technicians in possession of expert awareness — such neo-imperialists are able to immerse themselves in any position provided they are equipped in the safari-gear of irony. The result is a situation in which privileged scholars can "blacken up" or "drag up" and "play" with cruel stereotypes provided they do so self-consciously. Some perceive this as a "double-standard," however, it should be understood that this system of expertise is and has been the operating system of the technical society for many years. In a society which places such high-premiums on the power of information, its manipulation is a law unto itself, and thus not subject to calls for consistency or truth.

[11] My use of the term "accident" is inspired by Paul Virilio, who foresees an apocalyptic "total accident" of global proportions. For a good introduction to Virilio's discussion, please see Paul Virilio and Sylvere Lotringer's Crepuscular Dawn.