Drift

Jim Miller

Synopsis of Drift

"In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there."

—Guy Debord "Theory of the Dérive"

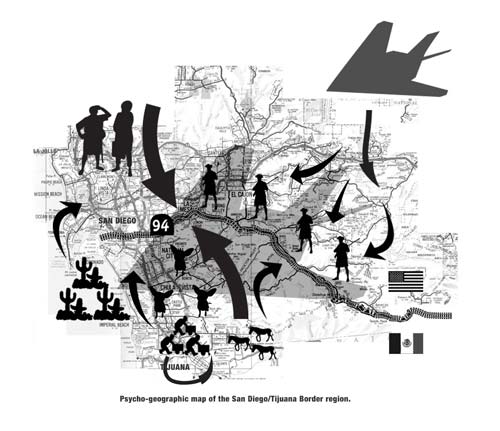

Drift is a novel composed of various intersecting narratives that combine to create a mosaic of the San Diego city space and the sea of lives that inhabit it. The central narrative charts a few months of the aimless life of Joe Blake, a downwardly mobile part-time English instructor and aspiring poet, as he falls in love with a former student, Theresa Sanchez, a single mother struggling to find herself in the midst of the daily grind. As the connection between the two of them becomes more profound, they discover a common yearning for a more authentic life, a deeper sense of being. On their journey they explore the meaning of identity, community, sexuality, spirituality, and justice.

This central story is interrupted throughout by minor tales that intersect with the main narrative. When Joe wanders through Tijuana, the reader also encounters a drunken sailor and a prostitute. Later on, the novel follows the descent of one of Joe's students into homelessness and insanity. This narrative is juxtaposed with that of a pious office worker fleeing to the suburbs at rush hour. As the novel continues, the minor characters include a retired cannery worker, a flophouse resident, a cultural critic, an editor, a labor organizer, a Vietnamese immigrant working in a restaurant, a Somalian taxi driver, a maid in a desert motel, a speed addict, an elderly blues man, a suicidal businessman, and others. Their stories range from the sacred to the profane and take the reader to a wide range of locations and consciousnesses.

In addition to these minor tales, the novel also includes a series of historical narratives that tell the story of the Mission Indians, the city founders, Emma Goldman, the Wobblies, the Theosophists, Henry Miller, Herbert Marcuse, the city's days as a health resort, farm labor wars in the 1930s and 60s, and the disaster of the Salton Sea. This historical metanarrative does not directly comment on the stories of the novel, but rather provides context for the story of the city itself and story of the time from which Joe ultimately cannot escape. Set in the late nineties, the novel captures the hollowness and unease that underlay the boom years. In sum, Drift is a philosophical, historical, and political novel that challenges traditional narrative forms and takes the reader on a journey that, hopefully, will result in both discovery and more questioning.

13

[1] Joe was dreaming in Technicolor of sitting by the window of an empty white apartment that glowed with a ghostly light. He was watching planes crash. They came in, one after the other, and either hit the ground producing deep red flames or exploded midair like fluorescent fireworks, popping into wonderful blue and yellow flowers, that slowly faded and fell just as the next plane went off. All of this was occurring against a pitch-black sky with no city lights, no stars. Joe felt a profound peace as he watched the spectacle, a calm at the eye of the storm. He woke up to the sound of a big jet cruising into Lindbergh, smiled, and got up to make coffee. It was 9:00 A.M. Monday, the first day of his week off before the summer session started. He felt light as he ate a banana, poured his coffee, and walked over to his computer to write:

I do not know what redemption is but I seek it —

Looking into the face of madness and guessing the meaning of dreams;

Walking through city streets, watching the strangers, and loving the dance of the

height of the day;

Reading the paper in a neighborhood diner, eavesdropping whenever I can;

Listening to the music of a foreign tongue, not knowing what anything means;

Driving through desert as the sun fades to evening, feeling alone in the world;

Making love in a strange room, so long and intensely that it feels like a trading of souls.

And if this does not save me, then perhaps just a minute more to ponder the

nature of non-being;

To remember vision through the eyes of a child;

To hear deeply into music, then sound;

To feel the rough edges of things;

To give into anger and yield to forgiveness;

To see myself through the eyes of a stranger;

To just be;

To pray without praying;

To dream a whole life in a minute;

To awaken to the rebirth of desire.

And if this too falls short, then grant me just one second more of diving deeply

into the texture of things—air, earth, water, fire, objects made and worn by

hands;

Of holding myself on the edge of abandon;

Of swimming in the center of delight;

Of the spark of passion in beautiful eyes;

Of the warm touch of skin—lips, nipples, stomachs, thighs;

Of a slant of ethereal light;

Of seeing the crowd as a family of being—feeling connected to a myriad of

strangers;

Of sudden and welcome revelation;

Of finding myself by losing myself;

Of looking long out my window at the skyline at night,

wondering and yearning for what

I don't know;

There are not words for everything.

I desire

and adore.

[2] It was a start, Joe thought, maybe he could do something with it. If only there was more time. Still, he felt good. He shut down the computer, turned on the radio and took a shower. The first story was an in-depth focus on a hate crime in North County. A group of migrant workers had been beaten and shot by a gang of young white men in a camp near Black Mountain Road in Carmel Valley. The migrants, many of whom were in their sixties, had been assaulted for hours. Eight white males with closely cropped hair drove up to the camp in a sports utility vehicle bearing pellet guns. They sprayed the men with gunfire, pelted them with rocks, hunted them down, and beat them with pipes all the while screaming racial slurs. One of them yelled: "Go back to Mexico" in broken Spanish. The migrants said the young men were big and had military haircuts. Sixty-one year old Jose Fuentes told the reporter, "They were playing with me. They were hunting me like a rabbit. They threw rocks at me like I was an animal." When the gunfire started he said, "All I could hear was the sound of the trigger. I didn't want to show my face because I didn't want them to leave me blind." Joe shook the water out of his hair. He felt vaguely sick as he listened. It reminded him of the black marine who'd been beaten and stomped to death at a party in Poway. Joe also thought of the reading he'd done yesterday about the vigilante mobs during the free speech battles here, and the vicious attacks on farm workers in the Imperial Valley in the thirties. The weather was going to be partly cloudy. He turned off the radio, got dressed, and sat down on his bed. It was 11:00 A.M. He decided to call Theresa Sanchez.

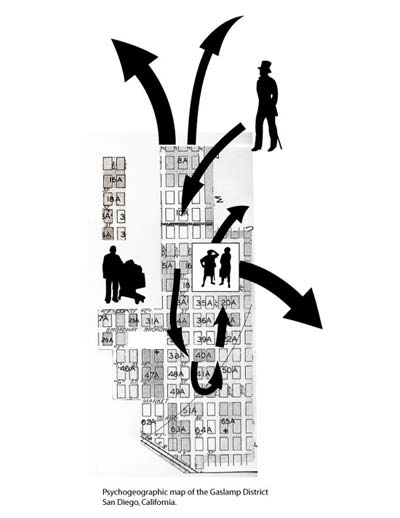

[3] Theresa wasn't home so he left a message: "Hi, It's Joe. I'd like to see you." He hated the sound of his own voice on the phone. Joe hung up, grabbed his wallet, and headed out of his studio. In the hallway, he could smell pot smoke and bacon grease. There was a transvestite with a five o'clock shadow getting into the elevator. A couple was fighting in the apartment by the door. Joe walked out onto 5th Avenue and squinted in the sunlight as he turned left on Hawthorne, went a block, and jogged across 6th Avenue to walk along the park towards downtown. The hillside leading up to Marston point was framed by eucalyptus and palm trees and covered with a carpet of lush green grass and white daisies. Joe hit the freeway bridge, passed a homeless man pushing a shopping cart, gazed up at the El Cortez Hotel on the hill above the interstate. The old landmark had been closed for years, but now it was an expensive condo complex, serving as one of the anchors of the aggressive gentrification of downtown. Joe had tried to walk into the lobby once. He was met by a pissy security guard who told him he was in a "private space," but that guided tours were available "by appointment." Joe walked on, glanced across the street at St. Cecilia's, an old church that was now a theatre, crossed Cedar, Beech, and Ash strolling by lawyer's offices, language schools, copy stores, pizza places, and bail bonds joints.

[4] At A Street, Joe stopped at a red light and looked over at the old Harcourt, Brace, and Jovanovich building that was now the World Trade Center. It was white with blue trimming, like a Modernist wedding cake. When the light changed, he crossed A and walked alongside the huge, ugly glass and concrete tower that was the Comerica Bank building. The pedestrian traffic was picking up now as people streamed out of the office buildings to have lunch as if they'd been freed from jail. Joe noticed a lot of nods to bohemia amidst the mostly white crowd: a secretary with a diamond nose stud, business men in black suits with shaved heads and earrings, neat little pony tails, funky sunglasses, tattoos peeking out from slit skirts and rolled up shirtsleeves. There were nods to punk, postpunk, goth, hippie, lounge, hip hop and rave culture. Hip is dead, Joe thought; the organizational man has e-mail, a cell phone, an SUV, and counter-cultural fashion sense. Even the older workers wore jeans sometimes. Only the smokers looked stressed and guilty, standing in doorways like pale outcasts of a fascist health club. He smiled at a pretty woman with long, curly red hair and Kokopeli earrings in a white t-shirt and a purple and blue Indian print skirt, carrying coffee and a copy of the Tao Te Ching. He thought he saw something in her eyes. She carefully ignored him.

[5] Joe moved on, looked up at the mural poking up over the Romanesque roof of the Southern hotel. It was a San Diego Union Tribune headline that read "America's Finest City." Joe crossed B Street, smirked to himself as he remembered reading how that name had been coined to make San Diego feel better after the city had lost the Republican Convention in 1972. He passed by the chic 6th Avenue Bistro that used to be McDonald's and the lobby of the Southern Hotel where a solitary old man sat, sadly reading the paper on a straight-back wooden chair. The front desk was closed, no rooms available. Joe passed a Mexican place, a drugstore, the Kebob House. Lots of the old stores and restaurants were closed down or closing. New places were under construction. Joe crossed the trolley tracks at C Street and gave a quarter to an old woman with no teeth in a Chargers jersey. He passed a coffee stand and more construction sites, looked across at a dead Woolworth's, hit Broadway and turned left. The office crowd disappeared as Joe strolled by Superfly Tattoo, Cortez Jewelry, and a language school. European tourists mingled with rooming house residents on the sidewalk. There were hotel workers, maids, and security guards in uniforms waiting at the bus stop. Joe walked past a Chinese Buffet, crossed Seventh Avenue, went by the 99 Cent Store and hit Wahrenbrocks' Book House next to the Dim Sum Kingdom.

[6] Joe nodded to the man behind the counter and walked up the dusty old wooden steps to the third floor where the San Diego section was at the top of the stairway. The dark musty quiet of the bookstore stood in stark contrast to the bustling street. It took a while for his eyes to adjust to the dim light. There was another room to the right and a half-opened door. Joe imagined secret rooms and passageways full of mystery. Once he could see, he looked over old maps of the city, histories of Balboa Park, a biography of Alonzo Horton, self published books about the Stingaree and Wyatt Earp. Joe picked up a used copy of The Journal of San Diego History with an architectural guide to the Gaslamp Quarter and noticed a whole row of novels by Max Miller: I Cover the Waterfront, Mexico Around Me, A Stranger Came to Port, and The Man on the Barge. He read the jacket descriptions and discovered that they were all thirties novels. Miller was San Diego's second rate Hemingway. Joe loved the charcoal drawings on the covers, the yellowed pages, and the smell of the past. He opened The Man on the Barge to the middle and read a passage: "Out here on the barge at night he felt off the world somehow. He was not of it. He felt as though he never would die, or had died already. He was not quite sure, nor did it matter. The water between him and the mainland formed a separation more mysterious than merely two miles of sea. The water could as well have been a void, a nothingness, and he was suspended beyond it." For Miller, it seemed, San Diego Harbor was at the end of the earth, a last resort. It seemed interesting. Joe kept it, grabbed A Stranger Came to Port as well, and walked downstairs to the counter to buy them. "I haven't sold one of these for years," the owner told him.

[7] Joe walked out of the store, stood onto the sidewalk for a second, and decided to turn left. He passed the Afrocentric Barber and a luggage store, crossed Eighth Avenue, and went by an empty Internet coffee house and the New Cafe, where the smell of egg rolls and Kung Pao chicken was flooding out onto the street. He noticed that Beanie's Lobby was open next door and strolled into the bar. It smelled of decades of cigarette smoke and stale beer. There were three sullen, silent barflies manning stools and nursing long necks. The bartender was reading the sports page and smoking. A staticky TV was showing the Padres game with no sound and no one was watching. Joe sat down and ordered a Bud. The bartender brought it to him silently and took the money. "Thanks," Joe said. There was no reply. This was like the last bar on earth, Joe thought, smiling to himself. Downtown had been filled with hundreds of these places about a decade ago. Now there were only a few dives left. Joe wondered how long the Lobby had until it became a fern bar. He took a sip of his beer and began to read in the dim smoky light.

[8] A Stranger Came to Port was about a businessman named Hardson who had run away from his job and family in Minneapolis, Minnesota and "disappeared" to live on a houseboat in San Diego Harbor with a scavenger named "Lobster Johnny." As Joe read on, he discovered that Hardson had had it with social niceties and obligations. Hardson was also sick of unions and F.D.R. He had escaped to a houseboat to watch the world go by, but had then decided to go fishing with a tuna boat. He admired the fact that, "fisherman alone remain the true link to the old days when all men were hunters." The problem today, Hardson thought, was that the inferior man was running things and punishing those who had shown the initiative to get ahead. A bit of a Social Darwinist, this Hardson, Joe thought. But just as Joe was about to put the book down, Hardson was contemplating nothingness like an Existentialist: "He could not comprehend nothingness. What was nothingness?" Joe took a slug of his beer and read about Hardson thinking that, "All men are part of each other." A few pages later he sounded Buddhist, then misogynist, and back to Social Darwinist. Hardson/Miller had a problem with philosophical consistency. But what struck Joe the most was the sense of aimlessness, desperation, and drift. It was as if one of the cranky retired fishermen who went to The Waterfront Bar and Grill had written a novel expressing all their unarticulated disdain and yearning. The government had killed the tuna fleets, but they had seen things, "Let me tell ya." Joe stopped after a passage where Hardson had pondered his loss of ambition, finished his beer and walked out of the bar, back to his studio to check his messages.

[9] Back in his studio, Joe was happy to hear the voice of Theresa Sanchez on the phone. She could see him next Saturday after her shift if he could pick her up at the bookstore where she worked in Old Town. Joe called back and left a message that he could. There was also a message from his friend Christine in Ohio. She had come out to school here with him back in the late eighties, but had gotten a job back home at Black Swamp State just south of Toledo. Joe called her and they talked. She told him stories about Black Swamp. A man who thought he was Jesus Christ went into the local bar and ordered a Martini and charged it to Yaweh. The man then walked across town to the Ford dealership and told them he was Christ in the form of Jim Thome, power hitter for the Cleveland Indians. Finally, our lord ended up on his front porch pouring bleach on himself as the police arrived. He was nude and told the police he was trying the clean off his whiteness. Another man posing as a team doctor for the college football team went to the homes of eight local families and gave their sons, all of whom had hopes of pulling a scholarship, proctology exams until one boy's mother asked why such an exam was necessary. Upon being questioned, the man fled into a cornfield, pulled out a gun, and shot himself in the head. The last story was about an English teacher who showed her class Star Trek videos every day for five weeks before disappearing without a trace. She was last seen wandering through the half empty Wood County Mall in full Klingon regalia. It was like a sick postmodern version of Winesberg, Ohio without the pastoralism, without hope. They said goodbye. Joe hung up without an ounce of homesickness.

[10] It was 3:00 p.m. and Joe had nothing to do. He put some Greg Osby on his stereo, walked over to his nightstand and grabbed a half-smoked joint and a book of matches out of the top drawer. Joe lit the joint, took two deep hits, smelled the thick sweet smell, and watched the smoke fill the air. Osby's jazz was one long song with no breaks——he drifted in and out of melodies separated by periods of prolonged dissonance. Joe lost himself in it. He struggled through a series of atonal notes until he hit a deep vein of melodic saxophone. It pulsed in steps like a heartbeat rising toward ecstasy. The phone rang and his machine took it. It was the credit card company hounding him for a late payment. Joe sighed, put the matches and the roach into his pocket, turned off his stereo and walked out the door of his studio.

[11] The hallway smelled like strong perfume, burned hot dogs, and his pot smoke. There was nobody there but he could hear muffled voices behind doors, a peal of laughter, and the sound of a TV game show. The late afternoon sunlight glowed around the front door, lending it an aura of gentleness. Joe walked out onto Fifth, crossed over at Hawthorne and kept going until he hit Fourth Avenue. He decided to drift downtown. At Grape Street he stopped to look at the huge Moreton Bay Fig alongside the parking lot that used to be the historic Florence Hotel. Joe tried to imagine what the grand old Victorian would have looked like. Did a man wander past this spot to ponder this tree a hundred years ago and wonder what it might look like now? How many people had idled here, thinking of love or death in the midst of an inconsequential day? The ghosts of the past haunt us, Joe thought, despite our efforts to exorcise them. He moved on past medical offices, a take-out chicken place, two bland hotels, and a rooming house.

[12] Past Elm he came upon the red brick gothic First Presbyterian Church. The stained glass windows were covered with Plexiglas and a gathering of homeless men lingered on the steps in front taking in the muted sound of the music trickling out of the church. Joe walked past them and into the church to listen to the organist practice. He caught the last few seconds of what sounded like Bach and followed the final dying note as it rose toward the arched ceiling. He watched the organist sit in the naked silence for a moment. If there was a God, it lived inside that silence, Joe thought. The organist turned and nodded to him across the empty pews. Joe said "beautiful" and left him to his solitude.

[13] He crossed Date Street where Olmsted had envisioned a promenade from the harbor to the park, walked over the freeway bridge where the growing flow of pre-rush-hour traffic hummed beneath him. Joe passed a law school and, in the midst of the crosswalk at Cedar Street, glanced toward the harbor. His eyes were drawn to a square of glistening silver framed by the main entrance to the Art Deco County Administration Building. It was like a door to a dream of pure light, so bright it hurt his eyes. A black Jeep honked, startling Joe out of his reverie and out of the middle of the street. He ambled by Catholic Charities and the cream colored Moorish tower of Saint Joseph's Cathedral with the red sun just above it. There were steel grates on the windows. It was as if they were afraid someone would steal God.

[14] Joe moved on, looked up at the open windows in the downtrodden Centre City Apartments where he saw an old woman sitting in shadows and a shirtless man with a hard face and a tattooed chest leaning out of a window smoking a cigarette, staring down at the parking lot. As he passed the lobby, he glanced in at the TV playing to an empty room as the desk clerk read a paperback novel. There was an angry, desperate looking woman cursing into the payphone outside the adjoining liquor store. Joe walked by another parking lot, the prison-like family court building, a live/work space with a Victorian front, the old cinderblock and iron Arts and Crafts Richard Requa building, and the Dianetics Foundation to Ash Street. At Ash, Joe was struck by the way the Imperial, Union, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America towers loomed, dwarfing the old H.B.J. building and casting long shadows on the street. They were graceless structures with no redeeming value, but their placement and size announced their dominance. We are your faceless masters, they said. Joe thought of Allen Ginsberg roaming the streets of San Francisco on peyote ranting at the St. Francis Hotel. He smiled and strolled by a hair salon in an old bank lobby, a concert venue that had also been a bank. Moloch, he thought, Moloch destroyer of men.

[15] At B Street, Joe looked up at the fading ad painted in red, green, white, and brown on the brick side of the vacant California Theatre: "San Diego's 'In Spot' on the corner of 4th and C." He walked by the boarded up window of what used to be a hot dog stand, remembered the smell of Polish sausages on the grill, the row of customers sitting at stools, resting their forearms on the greasy counter. The front entrance to the theatre was boarded up as well, plastered with dozens of the same movie poster featuring an ironic retro-seventies leggy platinum blond in hot pants, bent over a red Camaro, again and again. Someone had put stickers over several of the posters—sketches of the dead wrestler Andre the Giant's face with the caption "OBEY." Joe stopped and read the flyer entitled "Giant Manifesto" that someone had glued up next to one of the Andres: "The Andre the Giant sticker attempts to stimulate curiosity and bring people to question both the sticker and their relationship with their surroundings. Because people are not used to seeing advertisements or propaganda for which the product or motive is not obvious, frequent and novel encounters with the sticker provoke thought and possible frustration, nevertheless revitalizing the viewer's perception and attention to detail. The sticker has no meaning but exists only to cause people to react, to contemplate and search for meaning in the sticker." Joe saw little difference between the ad and the sticker. He noticed that passersby were looking at him as if he were insane. Who reads walls? He turned to go and glanced across the street at the Cubist-inspired mural on the side of the trendy live/work lofts above Mrs. Field's Cookies.

[16] Joe crossed C Street and noticed that the foot traffic was thicker. Office people were steadily flowing out of their cubicles to briefly join the homeless, the tourists, and the hotel dwellers. Joe passed by a man in a black Armani suit who embodied everything he hated—dark glasses, little gold earring, cell phone, neatly trimmed hair, gym-fit body, own the world walk. Something about him suggested the Internet, image management, heartless innovation, and a massive stock portfolio. If you ate his heart you would shit disdain, Joe thought. He wondered for a moment how he could judge so quickly on the basis of appearance until he heard the man say "Nasdaq" into his phone. Joe watched a group of women in pantsuits walk by with cagey eyes and careful postures. A couple in Sea World shirts were speaking French. After them followed a man in army fatigues with long hair and a stars and stripes headband, swinging a stick in the air as he said "dream flowers" to no one in particular. Joe took it all in and headed into the lounge in the U.S. Grant Hotel.

[17] It was dark inside and Joe blinked until he could see the parquet floor, the oak paneling by the bookshelves and the portrait of U.S. Grant above the fireplace and the luxuriant pool table. Joe decided to have a drink. He sat down at a table by the window and the proper-looking waitress came by to take his order—a vodka soda. She walked over to the bar and Joe watched her. She looked fragile, serious, but kind. There was an elderly man in a dirty yellow suit at the bar, eating all the bowls of cocktail peanuts. He ordered a glass of water and she brought it to him. The old man ran out of peanuts at the bar and moved to an empty table with a full bowl. After he finished, he relocated to a booth by the far wall to eat some pretzels. The bartender walked over and asked him to leave. Joe noticed the waitress looking on sadly, biting her lower lip. She brought Joe his drink. He paid and looked across the street at the lobby of the Plaza Hotel. There were people sitting in chairs watching traffic, glancing over at the lounge, waiting for no one, nothing. Somebody walked out of the lobby and into China King next door. The old man in the dirty yellow suit walked into the lobby of the Plaza. Joe sipped his drink, stared at the blue and white-checkered awning above the door of the Greek restaurant on the other side of the Plaza. The dentist's office was closed, as was Maria's Mexican food. Joe savored the tired, lonely block bathed in darkening shadows.

[18] He finished his drink, left a dollar tip, and walked through the lounge by the long line of booths against the oak walls with delicate fabric inlays to the hotel lobby. He strolled under a crystal chandelier and by a pair of antique wooden chairs to the men's room. He peed in a stall and took a quick hit off what remained of the roach, leaving the smoke in the air behind him as he left. Back in the lobby, Joe aimlessly wandered past oil paintings in ornately carved gilt frames—a dark forest scene, a dreamy pastoral river. He sat down in a chair in the corner and stared up at the elaborate gold and green moldings that bordered the ceiling. His eyes slid down the marble columns to the green carpet decorated with brown and tan medallions with flowers at their centers. There was oak around the doorways, rich red carpet on the stairs, a cream and gold filigreed iron railing on the walkway on the second floor. Joe thought of Emma Goldman in this lobby. She had wanted to address a lynch mob from an upstairs window. Brave sweet Emma in the pompous U.S. Grant. Her ghost was with him here, thumbing her nose at the dot.com nouveau riche. Joe felt a tap on his shoulder. A security guard was asking him to leave.

[19] Out on Broadway, Joe gazed across the street at the Irving Gill fountain in Horton Plaza Park, the water spouting up toward the Moorish copper cap before sprinkling back down the Doric columns into the octagonal pool. It was beautiful in the midst of the palm trees and potted plants behind chains. The grotesquely huge lizard on the Planet Hollywood sign, however, made the whole square absurd. Joe watched people carrying bags out of the mall as he crossed the street and made his way down Fourth, past the small park. He saw a group of Germans in beachwear sitting on backpacks alongside the wall of the mall looking in Let's Go California, teenagers with skateboards, preoccupied shoppers, happy hour seekers, and tired mall workers at the bus stop. Joe looked at people's feet—sandals, leather loafers with tassels, high heels, Converse sneakers, dirty boots, Doc Martins, running shoes, platforms, flip flops, Birkenstocks, pumps, and filthy bare feet. He looked up across the street at the tops of the turn of the century buildings in the Gaslamp, his eyes exploring the arched windows, elaborate moldings, peaked roofs, and Victorian flourishes. Joe imagined a street above the street, ramps connecting rooftops, winding purposelessly throughout the city, trading only in the commerce of wonder and sky. Above the jewelry store and the lobster restaurant, the new, Joe thought. He smiled and kept going.

[20] As he walked on, Joe glanced up at the domed top of the Balboa Theatre, decorated with blue and yellow mosaic tile and round portholes. The old Romanesque structure had been a vaudeville place and a movie palace in the 1920s. He stopped and read a sign on the wall with a picture of the lobby with its fine woodwork and elaborately sculpted waterfalls. Some vaudeville acts here had featured live elephants. Joe strolled on, past the window display on San Diego's history. He stopped and read a sign about how Alonzo Horton bought the site of the city for two hundred and sixty five dollars and built the Horton House where the U.S. Grant stands today. Boost it and they will come, Joe thought. The next sign was about the now-dead Chinatown and the red light district, the Stingaree. Joe had read about the brothels and opium dens. Ignored by the police, this area was riddled with maze-like passageways, hidden rooms, and secret chambers. There was a city beneath the city, subterranean spaces waiting. Joe dreamed of a labyrinth made for drifting. The architecture of his desire would open the maze beneath the city, creating a park beneath the streets comprised of passageways bathed in dim red light that occasionally opened to pool chambers, rooms filled with music of all kinds, snug little bars and opium dens, hidden libraries and free art galleries, rooms of light and color, beds for unashamed sex, spaces of pure silence, doors into mystery. A fat man in an ugly brown suit stopped next to Joe to read the same sign. He looked at him, smiled and said, "It was more fun then." Joe smiled back and nodded.

[21] The next sign was about Little Italy and the tuna industry. Joe looked at a picture of Italian and Japanese fishermen wearing straw and felt fedoras, hauling in tuna with huge poles. There were also photographs of the El Cortez being built during the Depression, the "nudist beach" at the 1935 Exposition, and the Douglass Hotel and Creole Palace nightclub. Joe studied a black and white photo of dancing girls and jazz players by the entrance to the Creole Palace, the girls kneeling in front smiling, the men standing behind them, holding saxophones and clarinets next to a sign that said "Harlem of the West." The final section was entitled "Boomtown's Still Boomin'" and was dedicated to hyping redevelopment and tourism. Joe read about the "visionary plan" for the ballpark, the "music village," the "urban art trail." The city was changing existing Fifth Avenue buildings into "a dynamic entertainment complex," the sign said. There would be "stylish nightclubs, exciting gourmet restaurants, upscale lofts, and expanded parking." The city was reinventing itself—again. He looked across the street at the Hard Rock Cafe in what used to be the Golden Lion and something else before that. He could see Victorian cupolas and the Hotel St. James rising beyond them on Sixth Avenue. Is history still history, Joe wondered, when it becomes a mere backdrop?

[22] Joe continued down Fourth Avenue past a taco shop, the F Street Bookstore, a cigar cafe, and two expensive Italian restaurants. He glanced across the street at the Moon Cafe and KD's donuts, funky remnants of the old downtown. The juxtaposition of these places with the sea of newness that surrounded them lent them the air of museum pieces, places where affluent diners and bar goers could glance in at gritty pockets of poverty. Perhaps they should pay the grizzled men at the counters, Joe thought, like characters at Disneyland. He remembered the fallen downtown with all the sailors, strip joints, diners, arcades, pawn shops, and porn theatres and was filled with a strange nostalgia for urban decay. Joe walked by the Metro Market and Wash, hit the Golden West Hotel and decided to walk through the lobby. The Golden West was built in 1913 but had none of the pretense of the U.S. Grant. People lived here. Joe looked down at the red Persianesque carpet and over at the worn Arts and Crafts straight-back chairs. One of them was occupied by a man with wild green eyes and bushy black hair who sat rocking, repeating "I got tired of making babies and dancing like Fred Astaire" over and over again. There was a fading painting of Torrey Pines on the peach wall above his head. It looked like a picture postcard from the twenties. Joe came to the ancient wooden front desk with grated windows, looked up at the cubby-holes for the keys and the mail, the "thank you come again" sign. To the right of the desk was a group of hotel residents sitting in big, battered rocking chairs staring at the huge TV screen. "America's Most Wanted" was on. To the left, the old switchboard was on display next to the vending machines and the antique phone booths. Joe looked down and noticed that the carpet had given way to black and white ceramic tile.

"Need a room?" said a voice from behind the desk.

"No thanks," said Joe "I'm just looking."

"Take your time," the voice said.

[23] Joe glanced back over at the people watching TV: an old woman in a red and black polka dot dress; two men in U.S.S. Constitution hats; a young girl with an old face, rocking slowly, not watching the show. A group of tourists, young women speaking Italian, came down the stairs. The TV crowd didn't look at them. Joe saw that one of the girls was stunningly beautiful. He stared at her luxuriant black hair, perfect olive skin, and full, sensuous figure barely contained by a little blue sundress. She stared back at him with bright piercing eyes, smiled broadly, laughed with her friends, and kept walking. Joe felt aroused and embarrassed, let them pass for a moment, and headed back through the lobby to Fourth Avenue. "I used to make babies and dance like Fred Astaire," said the man on the chair by the door.

[24] As he crossed G Street, Joe walked by an ugly apartment tower, the Rock Bottom Brewery, a cheese shop, and Hooters to Market Street. He passed an antiques store, Café Bassan, Café Sévilla, a new gourmet restaurant where the pie factory used to be, a sushi place, an electrolysis studio, and the Gaslamp Quarter Hotel. There was a new restaurant going into the Ah Quin Building. Ah Quin had been the "mayor of Chinatown" in the 1930s. His house was Spanish Colonial Revival style. Joe glanced over at the canary yellow Davis House museum, turned right on Island by the Horton Grand Hotel, built in the 1880s on another site and reassembled here one hundred years later. He glanced in the at the lounge, thought about a drink, changed his mind, kept going to Third Avenue, and turned left down the last remaining block of Chinatown. The Quong building used to be a brothel and an opium den and was now a chic Mexican café. Joe stopped and looked at Quin Produce across the street as a pedicab rolled by carrying two midwestern tourists in Green Bay Packers t-shirts listening to a canned litany of sanitized local history. He strolled past the Chinese Historical Building and read a sign that told him it was built by a cousin of Irving Gill's.

[25] Joe was struck by the fact that he was walking through a calculated pastiche looking for unplanned ruptures that let in the unexpected. He had hit a dry spell. He tried to stop thinking, let it go. Joe came to J Street, turned left and ambled by a parking lot. He crossed Fourth and glanced over at a billiards hall built to look old, a "real" old blue, yellow, and burgundy Victorian, Fifth Avenue lined with SUVs, a wine bank, an antique store, and a warehouse that was now apartments. At 6th and J, Joe noticed a mural painted on the side of a citrus warehouse—two huge staring eyes in pastel gold and turquoise with big black pupils under a single thick brow. Who is watching? he wondered. There were more antiques places, live/work lofts, and storage units. At Seventh, he turned right, passed Dizzy's jazz club, the Clarion Hotel, and more warehouses until he crossed K Street and saw the Western Metal Supply Company, the site of the new ballpark. At Seventh and K, Joe stopped and looked over at the frame of the new convention center, the shipyards and the Coronado bridge beyond it. In front of him was the huge empty expanse that used to be the warehouse district. It was fenced off. They had annihilated a piece of the city and were starting over. He tried to imagine the space of the city in a hundred years hence. Joe retraced his steps. At the corner of 7th and J, he noticed another pair of eyes staring over the top of a warehouse. Who was watching? What was it that connected him with the past and left his trace for the future? Who was watching? He didn't know.

[26] At Fifth, Joe turned right and walked past the Island Hotel and a Thai place that used to be the oldest Chinese restaurant in the city. He remembered the sawdust on the floor and the boxing posters from the thirties on the walls over the booths in the old Chinese place. He crossed the street and made a brief detour on Island to look at the Callan Hotel. It had been a Japanese business before it was stolen during the days of internment. There was a woman on the steps outside smoking a cigarette. Joe nodded to her as he looked up toward the roof of the building.

"You a student or something?" asked the woman before taking another drag off her cigarette. Her two front teeth were missing and her cheeks were sunken, but she had lively brown eyes.

"No, a teacher actually." Joe said a little awkwardly. "I'm just interested in buildings, history."

"Well, there's a lot of history in there," she said gesturing back towards the door with a gruff laugh. "History you don't want to know." She lit another cigarette and took a deep drag.

"You have a good evening," Joe said as he turned back toward Fifth Avenue.

"You too sweetheart," she said earnestly, "You too."

[27] Joe passed the Blarney Stone, an art gallery, more historic site plaques, yuppie party bars, a reconstruction of an Irish pub, a cigar bar, a sushi place, and another gourmet restaurant until he hit Market Street. While he waited at the light, he turned around and looked in the window of the wig shop on the corner. There were ridiculous fuzzy blue, red, and fluorescent yellow wigs on styrofoam heads with long necks, painted eyes, and cheap sunglasses. It was wonderfully absurd. Joe crossed Market and the weeknight crowd thickened. He passed by a group of sharply dressed Mexican teenagers on nervous first dates, some white skate punks with pink and purple hair, a pack of drunken office people, an ancient man with a gaunt, Creole face in a cowboy hat carrying a guitar case, two sailors in full uniform, people speaking a language he couldn't place, two hipsters with nose rings, one in a bowling shirt, the other in a t-shirt that said "Jesus is coming soon, look busy."

[28] A Japanese tourist was standing in the middle of the street taking a picture of the gold-capped cones and ornate Victorian decorations on the top of the Yuma Building. Joe glanced across the street at a family sitting at a table in the fancy new retro-fifties soda fountain that used to be the Casino theatre. He remembered seeing dollar movies there, reveling in the eccentric crowd of homeless people, sailors, prostitutes, security guards and janitors sleeping before the nightshift, whole families, seniors, vice cops, and drug dealers. It had been the kind of place where people talked back to the screen. Before that, it had been a porno theatre, before that, a respectable movie palace. Joe looked over at the Urban Outfitters that had been the Aztec theatre, back across the street at the Greystone Steakhouse that used to be the Bijou. He missed the gritty, chaotic democracy of the old dollar theatres. Anything might happen there, and frequently did. He remembered seeing a woman do calisthenics in the aisle during a horror film at the Bijou and watching a man stand up in the middle of Mississippi Burning at the Casino and deliver a political speech. They were just ghosts now, though, fading memories. There wasn't any room left for the cheap theatres or the people who went there. Everything had to be upscale, big money. He hated much of the gentrified downtown, but he realized that many of the old things he loved had started in the same way as these new places. The bright lights and the hype brought out the crowd and Joe refused to give up on the crowd. Even in the midst of the most calculated theme park zone, he thought, was the potential for a newness that superseded commercial intent. You have to learn to be surprised by the place you know, Joe thought, to find wonder and poetry in the street outside your door, to unlock the residual dream in the streets. He bumped into a light post and told himself to stop thinking.

[29] As he crossed G Street, Joe noticed that the avenue was even busier. He made his way slowly through the throng, glanced over at the long row of people waiting in line by the fake Victorian front of the new movie palace, passed by several Italian restaurants, smelling garlic, hearing the murmur of a dozen conversations. He weaved in and out of clusters of people waiting in lines or stopping to talk, ambled by Lee's Café, a pawn shop, Bella Luna, Little Joe's, Lulu's Boutique, and the Bitter End, a fancy martini bar that used to be the Orient, a sailor joint with huge fish tanks. Joe stopped for a moment and stood on the corner, losing himself in the river of faces. A gorgeous black couple kissed gleefully as they crossed the street next to a preoccupied waiter on his way to work. There was despair in the eyes of man in rumpled blue suit and joy on the face of a laughing secretary, playfully holding hands with a friend.

[30] For a moment, Joe imagined he could read the whole of people's lives in their faces and know impossible secrets. He glanced at a lovely woman in a long black evening dress and felt that tomorrow might be her last day. Joe laughed at his fancy, while still marveling at the awesome mystery of this random collection of human consciousnesses, thrown together here on this street at this precise moment in time by chance. He watched the woman in the evening gown stop to speak with a man sitting on the sidewalk with a cup. What was there between them? Between everyone? A kid with long cornrows in a 49ers jersey strolled by singing only to himself. The doorman stared lustfully at a woman in a very short red skirt. People touched each other as they zigzagged through the crowd. It was a warm night and the street was teeming with desire. All of us, Joe thought, are pregnant with death; all of us want our beings to sing in the time that we have. A little boy bumped into his leg and was dragged away quickly by his mother. Joe watched people watching other people as they made their way through the crowd. He gazed at people sipping wine in a restaurant patio and watched the way men and women looked at each other. At the most basic level, we want to eat, fuck, and sing, Joe thought. We yearn and hope. And for that moment, he felt a kind of undifferentiated connection to people that he knew would never last.

[31] Joe crossed F Street and looked up at the Keating Building, built in 1890, the office of the cheesy TV detectives in Simon and Simon. The sound of a tenor saxophone was echoing out of Croce's. Joe stopped outside the entrance, leaned on a light post, and glanced up at the Nesmith-Creely Building across the street, its red brick frame topped with marvelous spires. Next to it was a building with even more elaborate stonework, brown, green, white, and gold detailed woodwork, and two wondrous towers. It was twilight and the dying violet sky was blending with the glow from the street, giving the scene a feeling of magic. The saxophone rose and fell. Joe noticed that a homeless man was standing next to him looking up as well. Several other people stopped to glance up with them. "What's up there?" said a man gruffly to his wife who'd stopped to look because others had. "Wonder," Joe said before moving on out of the thick of the crowd, past one of the last peep shows, San Diego Hardware, Western Hat Works, Far East Imports, a couple of cheap restaurants, a sports shoes outlet, Lee's Menswear, an expensive new resort hotel, the Art Deco Universal Boot Shop, a check cashing place, Master Tattoo "since 1949," Subway, and Louisiana Fried Chicken. By the time he hit Broadway, the streets were nearly empty. There was vomit mixed with blood on the sidewalk. Joe looked at the bus stop a few feet away. A man was lying face down under the bench. Joe walked over to him. It was Bob Anderson. He took the last five dollars out of his pocket, leaned over, and gently stuffed the money into Bob's dirty jacket, taking care not to wake him. He didn't stir. Joe stood up and walked over to the corner to wait at the red light. It was dark now and his feet hurt badly.