Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 36 (2020)

15 Minutes of Existence During A Pandemic: Pseudonyms in Mail-Art and Social Media

Craig J. Saper, dj readies, and Craig Sapper

Abstract: Based on a College Art Association paper on “Not Utopian Dreams: 1960s Avant-Garde Conceptual Art As Warning of Our Current Crisis,” delivered on February 12, 2020, about a month before quarantines and lockdowns began, this article begins with a description of a slip of the tongue during the introduction to that paper. The slip, uncannily connected to the themes of the paper and the entire panel, leads to a discussion of pseudonyms in mail-art and social media. Against the intention of those involved in stamp, mail, and networked-art projects to produce a radically progressive politics and aesthetics, the anonymous and pseudonymous style now looks like the nefarious cyber-manipulations. Reading right-wing disinformation (that occurs by sending-on memes, tweets, and snippets), in terms of mail artists' "on-sendings allows one to see the contemporary mass manipulation as a logic, grammar, or structure. You don't need to intellectually agree with the message to send it on either in disgust, like, or laughter. That's how the earlier on-sendings work: no editorial judgement. They work before any interpretation or close-reading; they work before any established identity has claimed authorship (it could be a bot). The messages appear in a long anonymous chain. The key difference between manipulative cyber-media and networked art involves anonymity and pseudonyms. The participants and artists-audiences know who and where the messages come from; it is only the spying eyes of the delivery person or governmental investigators or marketers who saw only the pseudonym without an identity. It was anonymous for the censors and oppressors, and, at the exact same time, it is not even masked let alone anonymous for networked artists even though we all have well-known pseudonyms, handles, or a dj's monikers. The space between pseudonyms and anonymity determines its sociopoetic position.

In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.

-- Andy Warhol, August 6, 1928 – February 22, 1987

In the future, everyone will have a new personal identity for 15 minutes.

-- Peter Saper, 11:45AM to 12PM, February 12, 2020

After a technical error (a bad HDMI-cable took the blame as the tech. support had left the room and could not be found) led to a 20-minute delay to the start of a panel on “Analogue Rebellion: The Relevance of Mail-Art in the 21st Century” at the College Art Association on February 12, 2020, the panel organizer gave an excellent overview of the panel's scope and focus. Before each speaker, the same organizer and chair of the panel, introduced each speaker separately.

The first speaker, Margarita Lizcano Hernandez, was introduced. Hernandez, currently doing research at the Getty Museum of Art, described the history of Graciela Gutiérrez Marx's marginal mail art collective networks as a survival strategy in a situation of constant oppression and frequent “disappearances” (that eventually totaled more than twenty thousand people). It was clear from Hernandez's talk that something as seemingly frivolous as mail-art had serious intent, and further that the seeming anonymity of the participants allowed them to avoid not only censorship, but also death and disappearance.

After Hernandez concluded, the next speaker, Tom Wilkinson, was introduced. Tom, currently doing a post-doc at The Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Study, University of London, began his talk on the politics of postcards in 1930s Nazi Germany by showing an image of a postcard that was left anonymously in the streets of Berlin and seemed to make scatological fun of the Führer in a compromising position. Wilkinson described how this silly pornographic postcard depicted, in scribbled form, one male character bent over with his naked buttocks exposed with a larger man standing behind him; there was a disembodied phallus drawn on top of these images in case one missed the meaning of the two characters’ positions. The man bent over and exposed had his head turned to look out toward the viewer, and his face was un-mistakably that of the Führer. Wilkinson discussed how this postcard, and other similar ones, were left anonymously throughout Berlin. If the postcard artist was caught, then certain death awaited. Once again, mail-art had a serious and political intent. It also depended on anonymity.

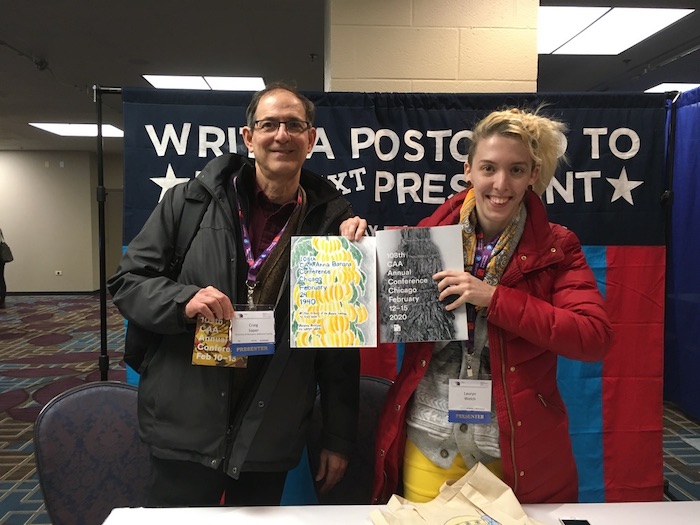

After Tom spoke, Lauryn Welch was introduced as an artist and “Cracker Jack Kid's kid,” and Lauryn's talk focused on the nuances and issues involved in growing-up and out of the mail-art networks. One slide showed a baby crawling out of the mailbox, and others were her name made into a stamped image sent out to an international network of artists and otherwise strangers around the world. Welch's identity was born in the mail. Welch further discussed how participation in the eternal network of community-building art projects became a literal mark, a tattoo on the back of Welch's head. The tattoo is an iteration of a Ray Johnson onsending of a doodled rabbit head that looks as if outlining a hand held in the shape of a bunny-head. The image appeared in countless iterations. It was drawn by so many artists that its maker's identity became distributed and shared, and became a singularly prominent marker of mail-art networks. Welch was literally marked, and yet by doing so had created an identity that was in and of the network: anonymized as an image even if the separate identity of the living person had a life of one's own.

The time for the panel was now running short. The panel organizer, noticeably trying to rush, introduced Peter Saper, and listed off a number of Peter's accomplishments, and had someone hold up Peter's latest book Readies for Bob Brown's Machine that was just published by Edinburgh University Press in January of 2020. With time running short, the next speaker was noticeably trying to deliver a talk that was deliberatively rushed and frequently interrupted by hecklers in the audience (with more about those hecklers later in this essay). When the last speaker concluded, the organizer went quickly to the podium, announcing that they would have time for a little less than 10-minutes for Q&A because of the shortened time because of the technical difficulties.

Peter Saper's paper began with a few thanks and acknowledgements, and then began with a framing of the paper in terms of Saper's earlier work. Since Saper's work is not previously published, and perhaps written by the author of this essay, it makes sense to not set it off with either quotation marks or block quotes.

For the first question, someone stood up and announced, as is typical of audience members attending academic conferences, that although they missed almost all of the panel and only caught the closing remarks of the last paper, they wanted to tell the panel and the audience about their background (“30 years of government security clearance”), a warning (“they are trying to kill the post-office”), the value of mail (“sealed in an envelope, without anyone allowed to open it”), and a liberating value associated with sealed private mail service (“queer mailings allowed us to survive without fear of censorship or arrest”). Although it did not address anything discussed in the panelists' papers, the statement by the audience member led the last speaker, Peter Saper, to redirect that statement into a different question relevant to the other panelists' actual papers: what role does anonymity play in the works you have discussed today? Near the close of the Q&A, the organizer then looked at the last speaker and asked, “Peter, in your work, ....” and finally, after letting the slip pass previously so as not to waste more time, the last speaker thought they should correct the slip or error. The person introduced as Peter decided that letting it pass a third time was probably now more like not telling someone that they have “egg on their face.” Saper thought of that colloquial expression in terms of how it etymologically alludes to dissatisfied audiences pelting performers with raw eggs. Saper's presentation had used an interactive structure precisely to push the audience out of a passive stupor through manipulation. To heckle and perhaps throw things at the speaker in disgust.

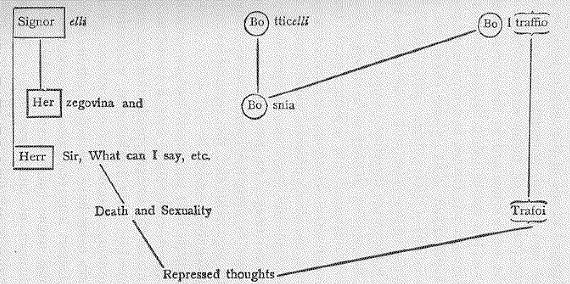

Once the panel organizer and chair recognized the slip, the chair said, “Oh my, did I say it before too,” and Saper said, “yes,” nodding politely. The chair was embarrassed, and added “I know his name from his work, and do not know where that came from,” and it seemed like an example out of Sigmund Freud's Psychopathology of Everyday Life. In the first chapter of that book, Freud explains that it is ...

not only forgetfulness, but also false recollection: he who strives for the escaped name brings to consciousness others -- substitutive names -- which, although immediately recognized as false, nevertheless obtrude themselves with great tenacity. The process which should lead to the reproduction of the lost name is, as it were, displaced, and thus brings one to an incorrect substitute.

Now it is my assumption that the displacement is not left to psychic arbitrariness, but that it follows lawful and rational paths. In other words, I assume that the substitutive name (or names) stands in direct relation to the lost name.

At the time, Saper thought of the presentation in terms of the audience's mediocre “team spirit” because they were lackluster in chiming-in when instructed to read portions of Saper's presentation as if heckling the speaker. The audience was conflicted wanting to hear Saper's plotting out of the history of mail-art as relevant to the 21st century. Of course, the chance slip of the panel's chair and organizer calling someone named Craig, Peter highlighted an important part of the presentation that otherwise would be lost. In fact, Lauryn Welch noticed the mistake, but knowing some of Saper's work, thought Craig was performing as Peter. Margarita chatted with Craig Saper afterward, and discussed how the earlier work on Networked Art had been an important influence on her own on-going work on mail-art. Saper could not help but think that the person delivering the paper was Peter, not Craig, Saper, and that the main lesson of both that earlier work and this essay is that changing the position of the speaker from the named speaker or author. The other panelist, Tom did not seem to participate, perhaps for good reason as Tom's paper dealt with politically charged anonymous postcards that if the identity was known would have led to exile, imprisonment, or death, and, perhaps knowing that anonymity is a deadly serious matter, did not participate; Tom also did not mention the organizer's forgetting my name.

Peter Saper was thinking about the expanded notion of formal analysis of giving a CAA paper. It was during those 15 minutes that there was an internal “recognition of reflexivity” and an “attention to the artifices of narrative,” as Caroline Levine explains, that shifted for Peter Saper “the pleasurable aim of the exercise of reading” a paper about the most interesting moments of the history of mail-art practices to a highlighting of the aesthetics and artifices of the narrative unfolding. There was a shift from “mere plots” to “aesthetic plans.” Much of this was lost on the audience as they wanted the unadorned story without any art or artifice. The irony of CAA's lack of art is often noted by those attending. Peter's paper instead “invited their readers” of the portions of the talk distributed to the audience “to investigate the rhetorical complexities of the experiment itself.” Saper “moved the attention back to the artifice, investigating the activity of reading and the artifice of the art object as the most interesting moments in the story.” The artifice of a CAA paper was reinforced not only by the paper that asked everyone in the audience to read one-line passages from the paper from their seats, but was further reinforced by the panel chair's mistake. Freud would look for the etiology of the mistake as he does in the important discussion of an acquaintance’s struggles to remember important names in art and art history. Freud diagrams the mis-remembered names and connects it to a specific set of circumstances.

All of this was in Peter Saper's mind in those fleeting minutes of Peter's public existence. The panel organizer did not explain where the name came from, nor did anyone ask, just as Freud's acquaintance was not consulted about the etiology of the slip. Both dealt with artists, art history, and aesthetics; both also hinted at the repressed thoughts of death threats and anonymous sexual and political harassment.

If one charts this slip poetically, as Freud does, one remembers it derives from the Greek, Petros, which translates as “stone” and became widely known as the apostle, Peter. Saint Peter comes to mind and is often represented in images as the guardian of the gates of heaven, the expert of experts in a hermeneutic of one's worthiness to enter heaven; Saper's paper and the entire panel dealt with that issue of avoiding censors and gatekeepers. Peter the Great, Peter Rabbit, Peter Pan, and other Peters appear as possibilities. Saper's shenanigans perhaps conjure a non-serious Peter Pan response to serious matters. Peter also, as a verb, signifies a fleeting and gradual fading as in the way Peter's mistaken name petered out, and was quickly forgotten as the slip was corrected. Bringing up Freud, one cannot help but think of the slang term peter as a reference to a penis dating from the nineteenth-century, but still in fading use. When used as a bridged noun and verb, peter is a an echo that is etymologically linked to Blue Peter, the invitation to one's Bridge partner to play a further lead in the suit being likened to the raising of a flag by that name with a blue background with a white square in the center, raised in navel communications when a ship is about to leave port. It is a performative way of getting around the censorial gaze of the opponents in Bridge.

Of course, the argument, rather than the sociopoetic form, of Saper's paper, which the panel organizer had read repeatedly in preparing the introductory remarks, was that the manipulative strategies and forms of earlier mail-art and other networked art was now being used by authoritarian regimes to manipulate large populations in cyber warfare and interventions in, for example, the presidential campaigns of 2016 and 2020. The argument in displaced form is that democracy and progressive liberation associated with mail-art has left the port -- and slowly faded -- only to be replaced or displaced by the phallogocentricity of the authoritarian patriarchy. Or, maybe it was something more mundane, but decidedly less interesting and less suited for a conference and panel focused on conceptual art practices.

A key developer of usability studies, especially in terms of avoiding mistakes in critical situations like airlines and aerospace engineering, Donald Norman discusses the difference between slips and mistakes in the section on “Two Types of Errors: Slips and Mistakes” in his book on the Design of Everyday Things. Norman begins with a “general classification of human error” that was developed with the aptly named psychologist James Reason.

We divided human error into two major categories: slips and mistakes. This classification has proved to be of value for both theory and practice. It is widely used in the study of error in such diverse areas as industrial and aviation accidents, and medical errors.

Of course, Peter Saper's entire presentation used mail-art activities as an analogy for presenting a paper at CAA. So, it played with the notion of “appropriate” behavior and form of the paper presentation. It was performing intentionally “human error” as “defined as any deviance from ‘appropriate’ behavior.” Norman explains that

errors have two major forms. Slips occur when the goal is correct, but the required actions are not done properly: the execution is flawed. Mistakes occur when the goal or plan is wrong.

Norman continues by explaining the etiology of slips and mistakes.

Slips and mistakes can be further divided based upon their underlying causes. Memory lapses can lead to either slips or mistakes, depending upon whether the memory failure was at the highest level of cognition (mistakes) or at lower (subconscious) levels (slips).

Peter Saper began existence as a slip which occurred when the panel's chair intended to say the correct name, and instead said something else: “In lapses, memory fails, so the intended action is not done or its results not evaluated.”

Here then was Peter's utopian dream of existence -- fleeting. Peter began by reading the title of the paper “Not Utopian Dreams: 1960s Avant-Garde Conceptual Art As Warning of Our Current Crisis,” and thanking Lucinda Bliss for organizing the panel and Peter's fellow panelists.

Let me begin by stating the obvious -- that the intention of those involved in stamp, mail, and all sorts of networked art projects was, and continues to be, motivated by a radically progressive politics and aesthetic position in relation to the traditional notions of the art-world's gallery systems, art-markets, and by extension to the large corporate media systems and the entertainment-military-tech-Bro and Petro-chemical complex motivating contemporary governmental policies and bureaucracies. In fact, it seems unarguable that one could label the goals of much of this artwork as working toward a decentralized progressive anarchy. I have detailed this understanding in two of my own books first in Networked Art in 2001 and then in Intimate Bureaucracies in 2012, and in numerous chapters, articles, and catalogue essays including one for the retrospective of Anna Banana's monumental exhibit that originated in Vancouver, went to Pratt in NY, and toured internationally.

That said, and made perfectly clear at the outset -- my talk today pushes against my own earlier optimism and conclusions about these artworks (that is, Peter had created a critical space between Craig's earlier work and Peter's petering existence), and the networked and sociopoetic projects that I (Peter? Craig?) have spent my career championing. Obviously, much has changed since my research (Craig) from 1980 through 2000 and also since my follow-up research in 2010 through 2011. So, unlike my fellow panelists or those involved in this type of work, my discussion today, or perhaps my provocation, is now pessimistic with a negative dialectical analysis of networked art as the precursor not of models of utopian sociopoetic formations, but rather cyber warfare directed against us.

In short, the structural economies, or what I call sociopoetics, of artworks like Ray Johnson’s “onsendings” and other mail-art projects, like Cracker Jack Kid's beautiful works or Clemente Padin's progressive politics that got him jailed by a fascist government -- now, in 2020, all seems to illuminate the workings of the mix that we all know too well of violent-libertarian-authoritarianist's cyberwarfare -- what we might call Putinism -- since many of the strategies involved were borrowed from the avant-garde writer and conceptual artist who was and still is one of Putin's closest advisors. And, yet much has changed and now Padin's work, all of mail-art, and really the postal service itself now seem our last hope before the fascists take-over more completely than they have already. See this recent mention in The New Yorker of an exhibit on mail-art that includes Padin's work. Mail-art and anonymous pseudonyms are both a dangerous sociocultural problem and an appropriate solution.

But before getting to those admittedly provocative conclusions, let me start by recalling some of the systems involved in this type of work.

Audience members were instructed on one side of a card on how to participate by reading out lines like these:

“On-sendings” and other mail-art projects, now, in 2020, illuminate the workings of the mix of violent-libertarian-authoritarianist's cyberwarfare -- that we might call Putinism.

On-sendings’ sociopoetics include participants’ desire for involvement in a network, the call to complete and send incomplete works, and outsiders' bemusement.

The instructions were printed on the other side of each card.

Instructions

- read the line on the other side of this card -- talk over the speaker.

- Read the line at least 10 more times over the course of the 15-minute paper.

- If you decide not to participate or leave, then please hand the card to someone else or to someone just entering the room.

On-sendings’ sociopoetics include participants’ desire for involvement in a network, the call to complete and send incomplete works, and outsiders' bemusement. This type of analysis starts with Yuriko Saito’s application of aesthetic interpretations, usually confined to artworks, to broader realms and everyday life outside of museums, galleries, and studios. To appreciate how both on-sendings and extreme rightwing bots manipulate participants, as the crucial aspect of the messages's content, one studies theories of gift exchange, desire and identification, and sociopoetics.

Media arts hide the production process and allow for a limited number of responses, the critics hoped to make audiences more likely to look for contradictions in mass-media messages.

The avant-garde and experimental artists dreamed of changing hearts and minds using automatism for progressive politics, and they would shudder to realize that extreme right-wing viral manipulations use those same strategies and structures; in fact, the lineage now includes Q-anon, 8chan, and Putin's manipulation of elections using a structure analogous to the sociopoetics of networked art. To illuminate this type of on-sending manipulation, I coined the portmanteau neologism, cyberripulators, that combines Cyber-, Rip (as in digitally copy and send on; to catch a wave in surfing social media; and also a tearing up of the legitimate news media channels), and (man)ipulators (with machines and superseding “man”). Reading right-wing disinformation (that occurs by sending-on memes, tweets, and snippets), in terms of on-sendings explains how these manipulative structures operate. Art history has urgent importance. You don't need to intellectually agree with the message just send it on either in disgust, like, or laughter. That's how on-sendings work -- no editorial judgement. They work before any interpretation or close reading; they work before any established identity has claimed authorship or even an identity. The messages appear in a long rhizomatic chain without any identity sending it directly to you. Peter might as well be on-sending it as it is a fake identity.

Chorus/Chora [although here reproduced single space, 12-point Times New Roman font, in the cards distributed the font was 16-point Helvetica; and the instruction to on-send was in 9-point]:

Extreme rightwing bots manipulate participants, as the crucial aspect of the messages' content, one studies theories of gift exchange, desire and identification.

Cultural and media theorists have for decades examined how spectators participate in their own subjugation to mass media's ideological messages, and in many ways in many of the projects involving mail-art networks -- the target was this same mass media and the loaded ideological messages that these artists literally cut apart into collages and spoofing of systems. One had to participate in these works to learn to re-use image banks. Loosening the image's power, therefore, depends on making audience members more aware of their role in partially creating media messages. In highlighting how mass media hides the production process and allows for a limited number of responses, media theorists, and networked artists alike, hoped to make audiences more likely to look for contradictions in mass-media messages. They also wanted to encourage audiences to become more open to experimental forms that demanded more explicit interactions during the interpretative process.

In addition to the instructions for audience interaction, Peter gave out other cards for “compliance officers” to control the audience in a simulation of trolls and counter-trolls. The instructions and lines were as follows:

Instructions

- WHEN anyone in the audience speaks, read the line on the other side of this card.

- Read the lines in order every time anyone speaks.

- If you decide not to participate or leave, then please hand the card to someone else or to someone just entering the room.

The compliance officers took their job seriously, and the scene became chaotic, and most people could not hear the actual paper -- even though the compliance officers asked that the speaker just “speak over them.”

QUIET!

QUIET PLEASE!

PLEASE BE QUIET! [TURNING IN CHAIR]

STOP INTERRUPTING! [GETTING UP HALF-WAY]

PLEASE STOP!

LET THE SPEAKER GO ON! [TURNING IN CHAIR AND POINTING AT SOMEONE]

LET THE SPEAKER GO ON! [TURNING IN CHAIR AND POINTING AT SOMEONE]

SHOULD WE CALL CAA SECURITY?! [SHAKING HEAD REPEATEDLY]

SHUT THE FUCK UP! [STANDING AND TURNING AROUND COMPLETELY]

SHUT UP! [EXASPERATED]

SHUT UP! [EXASPERATED]

SHUT THE FUCK UP! [STANDING AND TURNING AROUND COMPLETELY]

OH MY GOD, STOP HECKLING THE SPEAKER! [ALMOST IN TEARS]

PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE! GIVE THE SPEAKER A CHANCE! [GETTING UP AND MOVING TOWARD SOMEONE]

SHHHH!

Shush!

PLEASE! [TURNING IN CHAIR]

OH! [GETTING UP HALF-WAY]

STOP!

WHAT'S THE DEAL! [TURNING IN CHAIR AND POINTING AT SOMEONE]

LET THE SPEAKER GO ON! [TURNING IN CHAIR AND POINTING AT SOMEONE]

STOP [SHAKING HEAD REPEATEDLY]

OH MY GOD, STOP HECKLING THE SPEAKER! [ALMOST IN TEARS]

SHUT UP! [EXASPERATED]

SHUT THE FUCK UP! [STANDING AND TURNING AROUND COMPLETELY]

SHUT UP! [STANDING AND TURNING AROUND COMPLETELY]

SHUT UP! [EXASPERATED]

PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE! GIVE THE SPEAKER A CHANCE! [GETTING UP AND MOVING TOWARD SOMEONE]

QUIET!

QUIET!

QUIET!

QUIET!

SHHHH!

Shush!

SHOULD WE CALL CAA SECURITY?! [SHAKING HEAD REPEATEDLY]

SHUT THE FUCK UP! [STANDING AND TURNING AROUND COMPLETELY]

SHUT THE FUCK UP! [STANDING AND TURNING AROUND COMPLETELY]

SHUT UP! [EXASPERATED]

SHUT THE FUCK UP! [STANDING AND TURNING AROUND COMPLETELY]

OH MY GOD [ALMOST IN TEARS]

PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE! [GETTING UP AND MOVING TOWARD SOMEONE]

And, for this essay this point is key: You do not have to read the messages' meanings, but click on the bait to participate in an on-sending -- whether analogue or digital. At this point in the presentation, Peter had cued the audience to begin to read lines off of a card. They were extremely hesitant to do so, and many did not. Much of literary and media theories now, and some conceptual art projects, seek to highlight the importance of a reader's or spectator's interactions. Because of that emphasis, one might forget that these theories of reading and art-making, or more generally of ideological interpolation to the power of images, depend on a counterintuitive claim against the commonsense appreciation of reading and spectating -- an appreciation of following the artists' message, theme, or meaning; instead, we are asked to fill in the blank to make the meaning.

Audience interruptions, continued:

One might forget that these theories of art-making depend on a counterintuitive claim against the commonsense appreciation of following the artists' message, theme, or meaning; instead, we are asked to fill in the blank to make the meaning. Instead of “following a story” make a unique set of potentially infinite links among a set of linked texts.

The calls for interaction exist in every text, even in those hiding these possibilities behind an invisible style of natural realism.

The artists discussed on this panel make these links and associations precisely because these interactions defamiliarize habituated readings and art appreciation practices; these artists attempt to find unusual connections beyond the manifest reading of images. Manifest readings of obvious meanings, themes, or aesthetic forms have little place in on-sending art that seeks not only to open individual texts to other contexts, but to expand the definitions of reading and spectating. The calls for interaction exist in every text, even in those hiding these possibilities behind an invisible style of natural realism. The interaction exists implicitly in these texts; in networked media, and in performance and conceptual art, the call for response exists explicitly. Sculpting the social game around art-making depends on recognizing, like a potter who looks inside the pot that they have just thrown, the structuring absence and negative space only available after the pot has been made. It depends on the “nothings” of the non-event-hood and their respective contours, as well as on the sculpting work of influence, suspended between fandom and paranoia. The contemporary art discussed today in this panel speak to us about the processes and practices of contentless messages spread via auto-bot-on-sendings not just about an art historical moment that has passed or that functions only as a precursor to new and improved conceptual art practices. To understand the importance of on-sendings, influencing machines, global-grooves, and intermedia, one must wrest these works away from art and cultural history as these networked art projects offer a way to understand our cyborgian bot-induced influencing machine or cyberipulation, for short.

For Dick Higgins, it is “pointless to try and describe the work according to its resolvable older media;” the term intermedia describes “art works [that] lie conceptually between two or more established media or traditional art disciplines.” My definition of intermedia differs from Higgins's with regard to formal innovation: “The intermedia appear whenever a movement involves innovative formal thinking of any kind, and may or may not characterize it”; the last part of this sentence suggests the role I give to formal innovation in intermedia: formal in-novation is irrelevant to an object's or event's status as intermedia. A 1971 work by Fluxus artist Ken Friedman suggests these intermedia qualities: “The distance from this page to your eye is my sculpture.” Not only does the work poke fun at the normal criteria for sculpture, it suggests a particularly important interaction with the spectator. It goes beyond a mere criticism of art to suggest a social network built on playing with people, activities, and objects. Fluxus scholarship functions not only as a way to organize information, but as a way to organize social networks (e.g., people learning) based on interaction rather than on a sender-receiver communication model. In an issue of Edition Et, Fluxus participant Eric Anderson's contribution consists of three cards, each with instructions on one side on how to mail the card and these instructions on the other side: “don't do anything to this very nice card.” Typical of Fluxus work, these instructions put the participant in a humorous double bind and point to the social interaction involved in the work. In a letter to Tomas Schmit, George Maciunas argued that Fluxus's objective was social, not aesthetic, and that it “could have temporarily the pedagogical function of teaching people the needlessness of art.” This social project specifically concerns the dissemination of knowledge - social pedagogy. Simone Forti suggests that in the context of this social (anti-aesthetic) project, Fluxus work does not have any intrinsic value; the value of the work resides in the ideas it implies to the reader, spectator, or participant. She goes on to explain that

when the work has passed out of their [the producers'] possession, it is the responsibility of the new owner to restore it or possibly even to remake it. The idea of the work [ ... ] has been transferred along with the ownership of the object that embodies it.

Forti explains that the audience performs the piece in the process of transfer-ring the ideas; the work is “interactive.” This term suggests a shift away from the notion of passing some unadulterated information from an author's mind directly into the spectator's eyes and ears. Instead, the participants interact with the ideas, playing through possibilities rather than deciding once and for all on the meaning. A description of Fluxus “art games” by Higgins can function as a coda for the particular type of playfulness employed in the Fluxus pedagogical situation.

Audience hecklers:

Art discussed today in this panel speak to us about the processes and practices of contentless messages spread via auto-bot-on-sendings.

List a series of crucial elements in these art games, including a community of participants conscious of other participants ... “team spirit.”

Again, the authors leave the details of the actual event open.

Higgins writes that in the art games, one “gives the rules without the exact details” and instead offers a “range of possibilities.” He goes on to list a series of crucial elements in these art games, including social implications, a community of participants conscious of other participants (what we might call “team spirit”), and the element of fascination about when rules will take effect. Again, the authors leave the details of the actual event open; as others have noted; these works resemble scientific laboratory experiments rather than finished artworks. In discussions about electronic texts, the term interaction has a special prominence. One of the defining features of hypermedia concerns building in the demands for response by the reader or participant. When a reader “clicks” on a highlighted or underlined term in a text, the program replaces the text with another page of text. A reader's refusing to interact with these linked terms will limit a reading to one single page. The links allow the reader to navigate among pages from either one set of producers or throughout the World Wide Web. This ability to make links easily often encourages designers to structure Web sites into lists of lists. In that sense they replicate the earliest written texts of accountants' lists.

A number of commentators, including Walter Ong, have noted how written texts allow for the categorization essential to rational systems of logic. Electronic technology allows for an extreme version of something like Peter Ramus's rational logic based on relational branching lists. The mail-art networks foreshadowed these media technologies' peculiarities. Electronic technologies not only present these endless lists and lists of lists, they demand that the participant or reader “click” on terms to create new lists. This call for interaction changes the impact of the lists; no longer do they present a rational branching structure; the lists spread out in idiosyncratic routes according to any particular reading. The interactivity of these electronic texts also functions as the key factor in making electronic technology something other than an intensification of hierarchical branching outlines of organized information. Instead of imitating a singular rational thought, the links mimic the free association found in both brainstorming and psychoanalytic efforts to tap displaced sources of information. This type of eccentric reading practice has already found advocates in literary and cultural theories.

Audience:

Art history has urgent importance.

Just as the works discussed here today on our panel, multimedia employ these codes, Web pages and e-mail often highlight, literally and figuratively, call for response. Although it seems obvious that audiences play this crucial role, most literary and media analysis before mid-twentieth century examined only the construction of the texts or the historical context of the production process. The importance of an audience's response has always had a central role in media theories, at least since the beginnings of media effects research during World War II. In those studies, researchers showed new inductees in the U.S. Army propaganda films such as the “Why We Fight” series directed by Frank Capra. The social psychologists wanted to determine what effects these films would have on the new soldiers. The films sought to convince U.S. soldiers that the war was indeed a “good cause” in spite of enormous opposition to the United States entering the war and significant pro-German sentiment. The researchers concluded that the soldiers did not understand the films; they contained too much historical contextualization for the audiences to understand. The researchers concluded that the messages needed to be simplified. Before these studies, the role of the spectator in the creation of meaning was considered secondary to the actual message. After these studies, the role and experience of spectators became a major concern of social scientists and many humanities disciplines as well.

Experimental artists dreamed of changing hearts and minds using automatism for progressive politics.

They would shudder to realize that extreme right-wing viral manipulations use those same strategies and structures; in fact, the lineage now includes Q-anon, 8chan, and Putin's manipulation of elections using a structure analogous.

Reading right-wing disinformation (that occurs by sending-on memes, tweets, and snippets) in terms of on-sendings explains how these manipulative structures operate.

An aesthetic theory might describe the machinations of the automatic cyber weapons that endlessly send on messages using the same forms as mail artists, but on a wider scale for nefarious ends. We need to read the entire art history of what I have called intimate bureaucracies and sociopoetic networked art not as fanciful utopian images of worlds yet to come, but rather, and more urgently, as a way to understand the hilarious mass manipulation of the folie á culte -- or to read mail-art networks as models of, and precursors for, mass delusions of our apocalyptic fantasies rushing toward the fire and wars as part of an elaborate paranoid on-sending. The on-sending for this panel was sent by the organizer to Craig, but Peter delivered the paper before being snuffed-out of existence by Craig after the paper was delivered.

Dear Craig,

I am pleased to inform you that your proposal for a paper/presentation has been accepted for the session, “Analogue Rebellion: The Relevance of Mail Art in the 21st Century.”

Please remember that all participants are required to be current CAA members from today’s date through at least February 15, 2020 in order to serve as speakers. If you are not a current member, please contact CAA membership: https://www.collegeart.org/membership/individual. I will be uploading presentation information into CAA’s online portal in September, and you will need to have a current CAA membership in order for your abstract to be properly uploaded into the conference materials.

All conference participants, regardless of role, must also register for the conference (registration may be full-conference or a single-session ticket for the session in which you are participating). If you have been accepted as a speaker to another CAA 2020 session, please notify me immediately about which session you plan to speak in, as you may only serve as a presenter once per conference.

For other logistical questions, please refer to the Frequently asked question page on CAA’s webpage. https://www.collegeart.org/programs/conference/FAQ. Thank you for agreeing to participate on the panel. Your perspective, among the presenters, is unique, and I know that your participation on the panel will be a valuable contribution to the success of this session. I look forward to working with you in the coming months. I will be in touch soon with more detail on process and approach. As I consider the final composition and structure of the panel, I may suggest an alternative format to the Q-n-A following our presentations. More on that soon. In the meantime, welcome aboard!

Best Wishes,

Lucinda Bliss

Soon after delivering the paper, Craig saw a building in Providence, Rhode Island, that had a vacancy that suggested the Bliss Place panel and the absence of Peter in that “Space Available” sign.

Loosening the image's power, therefore, depends on making audience members more aware of their role in partially creating media messages.

Electronic technologies not only present these endless lists and lists of lists, they demand that the participant or reader “click” on terms to create new lists.

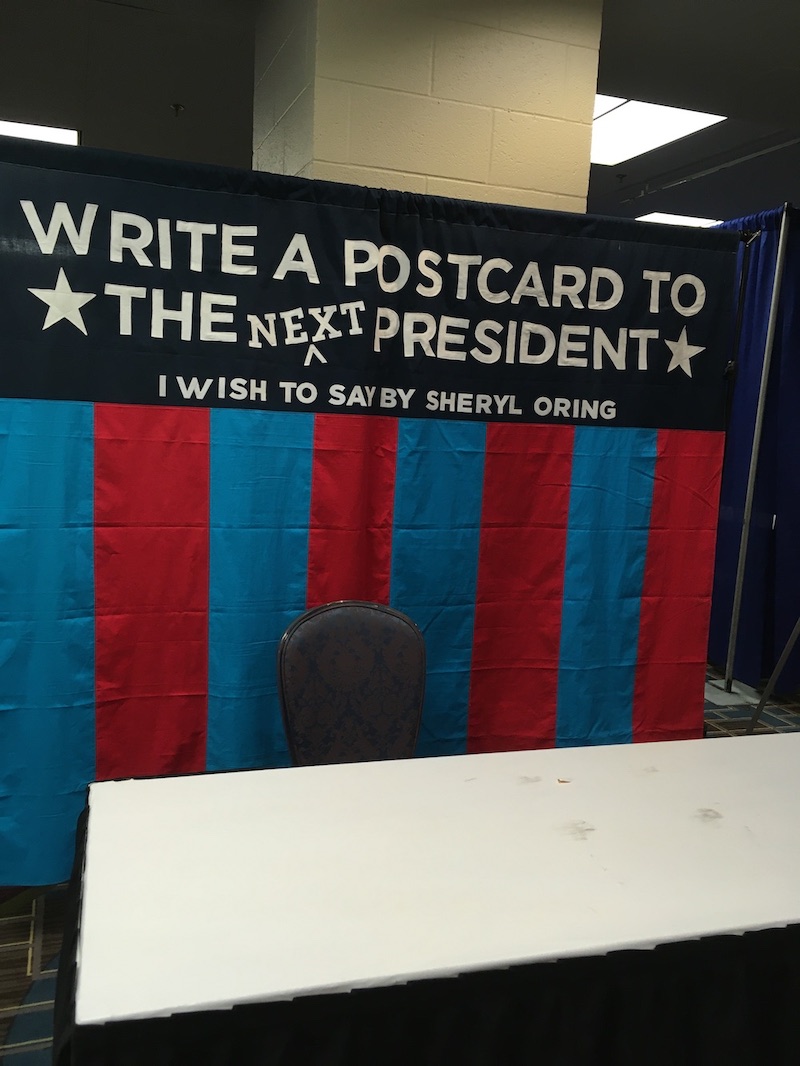

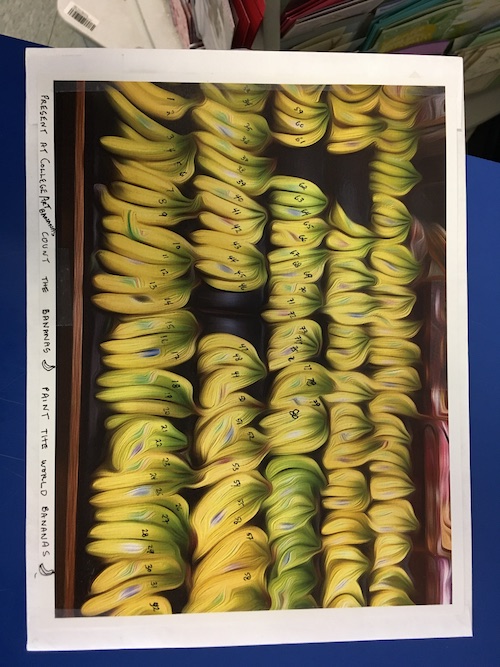

After the panel, one of the panelists, Lauryn Welch, helped me complete a mail art project celebrating Anna Banana's 80th birthday. We made a parody of the CAA conference brochure and panels. In keeping with mail-art practices, everything was documented. We chose to document it in front of Sheryl Oring's brilliant and, for this essay particularly apt, “I Wish To Say” project, that I had long ago promised Sheryl that I would write about after meeting Oring at another CAA, and discussing the on-going work. Well, although Craig Saper never got around to writing about it, perhaps Peter's and dj readies' contributions are an on-sending of Oring's work?

Although I do not know if these or which of the interruptions were read or not as I was trying to read my paper (and read it in a way that would invite interruption and heckling over), these are more audience on-sendings that were meant to be read over the speaker or interrupt this essay in a dialectical Brechtian reaction to the cyber-attacks and manipulations that depend on on-sendings:

Lists spread out in idiosyncratic routes according to any particular reading.

Instead of imitating a singular rational thought, the links mimic the free association found in both brainstorming and psychoanalytic efforts to tap displaced sources of information.

Just as the works discussed here today on our panel, multimedia employ these codes, Web pages and e-mail often highlight, literally and figuratively, call for response.

Researchers concluded that the messages needed to be simplified. After these studies, the role and experience of spectators became a major concern of social scientists.

An aesthetic theory might describe the machinations of the automatic cyber weapons that endlessly send on messages using the same forms as mail artists, but on a wider scale for nefarious ends.

A way to understand the hilarious mass manipulation of the folie á culte -- or to read mail-art networks as models of, and precursors for, mass delusions of our apocalyptic fantasies rushing toward the fire and wars as part of an elaborate paranoid on-sending.

Conceptual art projects, like mail-art, seem frivolous at first. The pseudonyms suggest anonymity, but, in fact, what is key is that unlike the online cybermanipulators, the participants and artists-audiences knew who and where the messages came from; it was only the spying eyes of the delivery person or the governmental investigators or even marketers who saw only the pseudonym. It was anonymous for the censors and the oppressors, and at the exact same time it was not even masked let alone anonymous, and that is the key as we make clear in all of the work of dj readies, Peter Saper (RIP), and Craig J. Saper. If we began pessimistically, we conclude with an opening that suggests that interactive, performative, and even manipulative works with pseudonymous creators distributed in a network are very different when taken as an exchange of ideas, art, and mail rather than as a reified given. The mail artists sent out a message: it could be otherwise; it could be an expanded notion of identity; it could model an intimate bureaucracy.

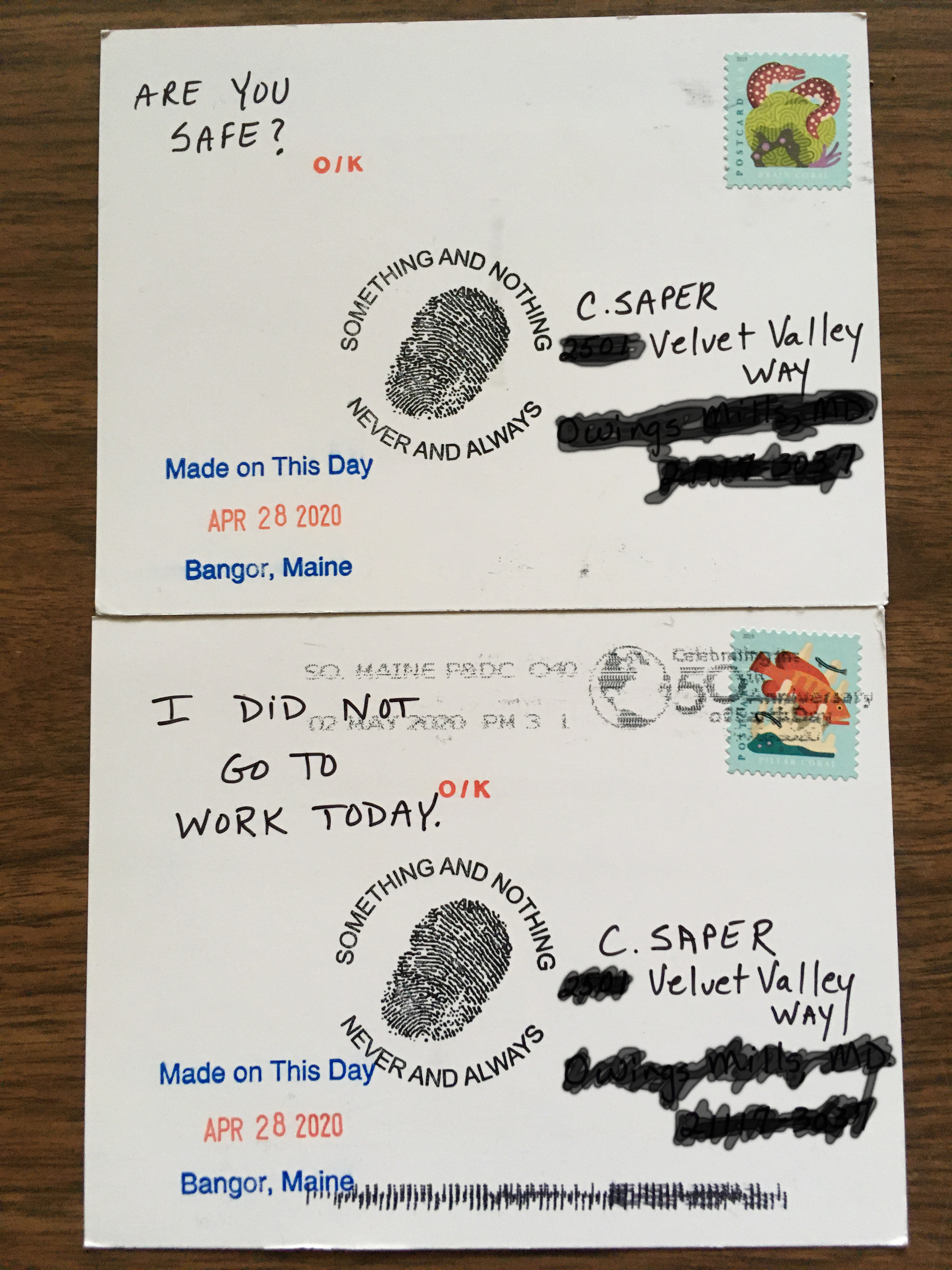

During the self-quarantine, I continued to receive mail-art including these from Owen Smith.

And scholars continue to “get” my work even as they get my name “wrong” -- it is unavoidable.

Notes

- Sigmund Freud, Psychopathology of Everyday Life (New York, NY: The Macmillian Company, 1915): 4.

- Caroline Levine, The Serious Pleasures of Suspense: Victorian Realism and Narrative Doubt (Charlottesville, VA: The University of Virginia Press, 2003): 198.

- Ibid., 198.

- Freud, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, 9.

- Donald Norman, The Design of Everyday Things (Basic Books, 1988): 170.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 171.

- Craig Saper, Networked Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

- Craig J. Saper, Intimate Bureaucracies (New York, London, Baltimore: Punctum Books with Minor Editions and AK Press, 2012).

- “The Banana Paradox” in Anna Banana: 45 Years of Fooling Around with A. Banana, ed. Michelle Jacques (Vancouver and Victoria, BC: Figure 1 Publishing and Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 2015).

- Ray Johnson’s on-sendings are a series of artworks.

- Saper, Networked Art, 20.

- Ibid., 66.

- See Natan Dubovitsky, Vladislav Surkov, Almost Zero (New York, NY: Inpatient Press, 2017); Harriet Staff, “NYR Daily Reviews Almost Zero, Inpatient Press’s English Translation of a Novel by Putin’s Right Hand,” Poetry Foundation (January 23, 2018).

- Yuriko Saito, Everyday Aesthetics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Dick Higgins, “Theory and Reception” in The Fluxus Reader, ed. Ken Friedman (Chichester, UK: Academy Editions, 1998): 222.

- Dick Higgins, Some Poetry Intermedia (New York, NY: Unpublished Editions, 1976), reproduced in Dick Higgins Intermedia, Fluxus, and the Something Else Press: Selected Writing by Dick Higgins, ed. Ken Friedman, Steve Clay (Catskills, NY: Siglio, 2018): 241.

- Saper, Networked Art, 20-21.

- Ibid., 44.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 45.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Why we Fight, directed by Frank Capra (1942-1945; USA: United States Office of War Information), DVD.

- Lucinda Bliss, letter to author, September 24, 2019.

- Sheryl Oring, I wish to say: The birthday project (Ann Arbor, MI: Quack! Media, 2008); Sheryl Oring, “I wish to say” (performance, College Art Association Annual Conference, Chicago, IL, February 12, 2020).

Cite this Essay

Saper, Craig J., dj readies and Craig Sapper. “15 Minutes of Existence During A Pandemic: Pseudonyms in Mail-Art and Social Media.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 36, 2020, doi:10.20415/rhiz/036.e09