Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 36 (2020)

‘No Pigs in Paradise’: Speculative Materialism in the Spirit of Black Constellation

Balbir K. Singh

Virginia Tech

Abstract: In this article, I study the contemporary multimedia arts collective Black Constellation. I analyze how these cultural producers place creative and political collaboration as a form of solidarity, and how such solidarity necessarily means the recognition of discrepancy and difference as an inherent strength in creating forms of radical kinship. This kinship model is one that I name the “Black Brown Indigenous Subaltern Alien,” a kind of refrain that puts into view the ways these various bodies inhabit alterity and minoritarian subjectivity without separation or annexing. I name this kind of visionary work “speculative materialism,” insofar as it theorizes relation and connectivity amongst different historical subjectivities and material conditions. Given that the project of liberal modernity has taken up the work of classification, differentiation, and taxonomizing in the name of upholding structures of statist and majoritarian power, most especially white supremacy, I am especially drawn to the Constellation’s ability to maintain commitment to bridging respective and distinct histories for its future vision.

“Our past is the western world’s future.”

– Maikoyo Alley-Barnes

YOUR FEAST HAS ENDED

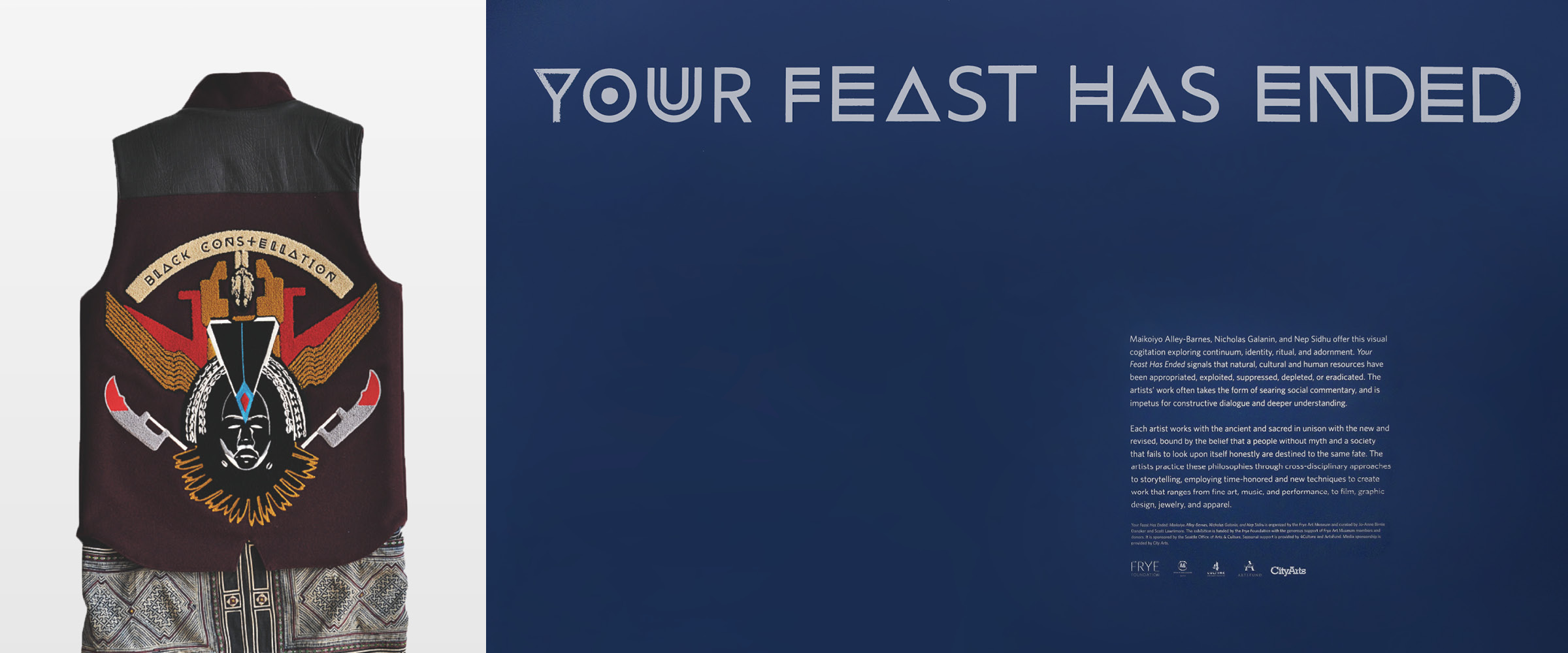

In the summer of 2014, Black Constellation was cemented as a creative force of the global underground, when three of its artists put on a major exhibition at the Frye Art Museum in the First Hill neighborhood of Seattle. The artists included Black Seattle-based artist, filmmaker, writer, and designer Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes; Punjabi-Sikh Toronto-based, sculptor, painter, and clothing designer Nep Sidhu; and indigenous Tlingit Alaska-based conceptual artist Nicholas Galanin. Their exhibition was titled YOUR FEAST HAS ENDED, with the earlier longer title, “O YE PARASITES, YOUR FEAST HAS ENDED.”

This exhibition included critically-lauded hip hop duo Shabazz Palaces through a collaboration with the visual artists, where they added a one-day, four-hour long sonic sculpture titled “Expanding the Now: The Continual Line.” Having formed in 2010, Black Constellation is comprised of many artists working in many forms: Seattle-based Shabazz Palaces, members Ishmael Butler and Tendai Maraire; musicians Erik Blood, OCnotes, Erykah Badu, and THEEsatisfaction members Stasia Irons and Catherine Harris-White; visual artists Kahlil Joseph, Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, Nicholas Galanin, and Nep Sidhu. While the Constellation had loosely formed only a few years prior, it was here where the public was allowed access to the work across different artists within the collective, and where their aesthetic and political cross-pollination is best exhibited. In its mode of address, that YOUR FEAST HAS ENDED, the minoritarian is summoning and confronting the dominant, the majoritarian, the consumptive, the greedy—their time is up.

Alternately qualified and not qualified with “the,” I turn to the words of one of the multimedia arts collective’s visual artists, Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, describing the constellation:

The Black Constellation consists of a unified cross-disciplinary guild of Soothsayers, Makers, Empaths, and Channels. Their terrestrial offerings have been myriad, including sentient offspring production, the facilitation of cultural phenomena, the perpetuation of ancient ritual, and the undertaking of the new and remarkable. In all things, The Black Constellation combines the astral and the earthly, the gorgeous with the abjectly honest, and the ancient with the as-of-yet unimagined ... all the while remaining in constant communion with the Sacred.

The gifts of Black Constellation are weighted by sacredness, as Alley-Barnes describes; they are mediums through their art and practice, between ancient and future worlds. Through their multitude of forms and styles, the collective creates visually, sonically, textually, practically, affectively, performatively, and abstractly, all at once. Alley-Barnes describes Black Constellation through the language of human transmission from our planet including various manifestations, offerings that are simultaneously full of divine beauty and reflective of worldly trouble: this is work out of this world and very much of this world. Indebted to histories and creators of new horizons, Black Constellation bestows art and practice for the Black, Brown, Indigenous, Subaltern; for those relations of the South-South, the internationalist, the native, the immigrant, the alien—those displaced from and without a home. In such a configuration, they constellate two worlds: one, a world sedimented out of histories of chattel slavery, colonial violence, imperialist wars, land dispossession, police violence, environmental degradation, forced migration, and resource extraction—all of the world’s old and new violations against its Black and Brown peoples; a second, an alternative, other-world, a vision that sees the present for what it is and constructs the future as a necessary inversion. Black Constellation is of an AfroFuturist sensibility, one that arrives as alien under conditions of alienation. In the face of such nods, forward and backward, historically and futuristically, the collective remains steadfastly in the present.

While the cultural work they are creating is certainly resonant with other artistic acts, especially within music and hip-hop specifically, I highlight their commitments to collective and multitudinous artistic practices. More precisely, I find immense value in the work they do to center, exalt, and make divine minor and subaltern experiences. For example, while the artists within the Constellation are primarily male-identifying, there is a deep-rooted investment in the figure of the woman, and what Sidhu has named “the divine feminine.” For my purposes, I argue that the work of Black Constellation provides an important example of both aesthetic and political solidarity and coalition. Their work exhibits for minoritarian communities anti-colonial modes of style and expression, especially vital in the face of ever-encroaching colonial and capitalist extraction.

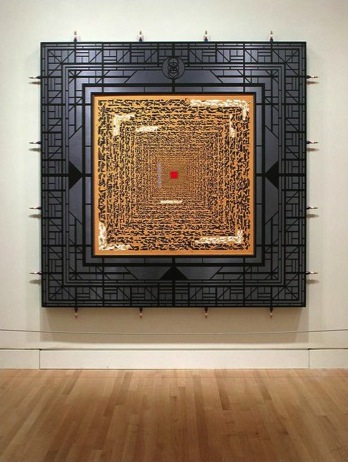

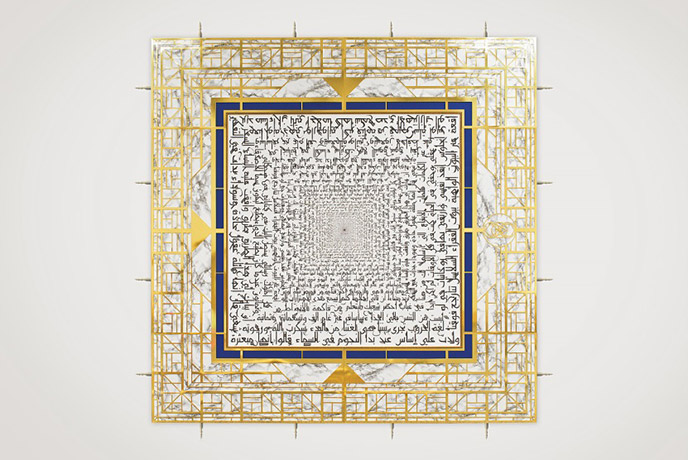

For example, Nep Sidhu’s Confirmation series (A, B, C, with A and B as figures 2 and 3), is a set of images wherein Sidhu creates what he names a “third space, a space between the practice of writing and the practice of architecture.” Sidhu uses the ancient Arabic calligraphy script, Kufic, to relay messages within this series. Sidhu has commented that Confirmation A is supposed to represent the transition from the linguistic to Confirmation B’s transition to the architectural. In an exhibition catalogue of this work for Sidhu’s first solo show, just outside of Vancouver, British Columbia at the Surrey Art Gallery in 2016, the Confirmation series is described as such:

In Confirmation A the square calligraphic ink on paper composition translates a poem by Black Constellation member Ishmael Butler, describing his birth into this world with an understanding that was in place long before assuming physical form. Sidhu summarizes aspects of the letter: “During one’s time here on earth, the dance of ego, expectation and ethics continue to crash incandescent new black waves of purple and gold against a lone stone, creating a rhythm-like mantra that allows the listener to walk away with a new set of confirmed questions.” This text is based, in part, on the first time the artist met Butler and realized their “shared function” as creators and the beginning of their shared collaborative work. The words written in the central panel of Confirmation B are based on a letter written by the artist to his mother after her passing a number of years before. The letter expresses his hope in finding her in her next cycle, and to fulfill a promise made to her that the continuation of his art practice would allow her the possibility of an “eternal presence.” Words written in colours other than black are based on statements that were last spoken to the artist by his mother.

It becomes possible to read these parts of the series as a method of communicating the durational aspects of Black Constellation’s creative drive to make art as part of their collaborative and respective lives. Sidhu’s words stress an attunement with honoring the deceased, as their spirits indelibly affect the practices of the living. In both works, art-making is at stake, and the intentions, questions, and effects of such cultural production are made manifest through text that is purposefully illegible to most viewers. While many might recognize the script as Arabic, that is likely as far as they might get in terms of translation and thus a fuller understanding. What is more lies in the concept of these works engaging the linguistic and written with the architectural and sculptural. The visual effect of the text as spiraling in or out lends a sense of depth, giving the Confirmation series a sculptural component. And with the composition of each, the border emanates as though a blueprint for the fortress of words spun in Kufic, composing a dizzying and mystifying cumulative effect. Thinking, too, of the messages Sidhu is attempting to convey in these pieces, I am particularly struck by his use of the Kufic script, taught to him by a local imam in Toronto, as a script devoid of any particular personal or Constellation connection: such a fact makes the deployment of the script a notably unique choice, connecting the Constellationeers’ already varied traditions and histories, to yet another distinctive tradition and history. Sidhu’s choice is thus another mark of Black Constellation’s investment in ancient traditions and future-oriented practices, especially those traditions and practices outside of liberal, Western, and colonial modernity.

* --- *

In this piece, I consider Black Constellation’s work to think and theorize otherwise through divine works of culture and creativity. I situate my intervention as one invested in both the cultural turn’s historical and analytical stakes, as well as invested in Marxist analysis; with this latter investment, I refute cultural production as subsumed under economic production through my article’s reading of Black Constellation’s transformative work. As such, I underscore the process of meaning-making that happens through the collective’s many forms of art, imbuing their work with visible symbols, audible references, and felt or textural signs. These symbols, references, and signs, offer many things: their familiar meanings, along with their multitudinous related and unrelated possible meanings—in other words, the ways they are overcoded and proliferate meaning in relation to their contexts. In essence, this highlights how cultural production must be understood through the varied historical and material contexts and continuities between the Constellationeers.

Furthermore, in my emphasis on both Black Constellation’s invocation of the sacred, and my reading of much of their work as sacred, I am speaking to the material conditions under which such work is produced—conditions in which minoritarian cultures have survived, persisted: I argue that this survivance is the basis for anti-colonial modes of rethinking and reimagining the otherworldly. I analyze this collective as a model of what I name speculative materialism: such a concept bridges the practice of speculation—through art, theory, and other forms—with embedded histories and grounded realities. I offer a theory of the relationship between speculation and historical materiality in the study of culture, hinging on the concept of what I call radical kinship, which I explain shortly. The merging of speculation with materialism may appear paradoxical; however, I offer this term as a means of grappling with how artists such as those in Black Constellation engage across a historical continuum that offers a future vision, especially given their investment in honoring the experiences of their communities—most notably women and elders. Such a concept falls very much in line with futurist thought—including Afro-futurism and Indigenous futurism—as well as theories around science fiction, utopian, and dystopian thought.

Part of how I employ this concept of speculative materialism is through multiple adjacent and influential terms and ideas, including constellation, abstraction, and radical kinship. Constellation in this context is very much grounded in blackness, and enables a new rigorous paradigm for seeing asymmetry, speculating how it can connect forms of redistribution and do redistributive work. Such redistribution indicates the way that the respective communities of which the Constellationeers are a part have been and continue to be exploited and violated, and that forms of reparation or redistribution are the only ethical forms of redress in the face of ongoing colonial and capitalist conditions. Moreover, I deploy abstraction as a mode in which to describe the work of Black Constellation as one that predominantly works against forceful intelligibility or towards forms of illegibility. In this way, abstraction can line up with the art world’s notion of conceptual art, a realm often cordoned off as the territory of elite white artists. Black Constellation’s form of abstraction is one that often obscures the direct linkages of the politics and pasts from which it is inspired. This form of abstraction feels organic in the case of the collective, and this comes through most clearly in their collaborations.

Finally, I give the name radical kinship to these linkages to politics and histories in their artistic vision, creation, and collaboration. Radical kinship is a concept that I propose as offering forms of connectivity and relation across time and geography—akin to what Lisa Lowe calls asymmetry within the path-breaking study of “the intimacies of four continents.” Similar to solidarity, radical kinship puts into conversation multiple distinct and respective historical conditions and material realities. What is particularly important to note is that radical kinship does not appear as clear or apparent to the viewer or audience, as it is often subtly integrated into the work itself, whether through collaboration, critique, or curation. Given their anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and anti-police politics—in the context of the U.S., Canada, India, and globally—Black Constellation’s critiques and affinities are interwoven in both obscure and apparent modes. Radical kinship gives a name to these historically-motivated, politically-inflected creative endeavors by the Constellationeers. In my study, it is through and for an anti-colonial radical kinship that Black Constellation makes its most crucial creative intervention. As such, the stakes lie in thinking with such anti-colonial logics, as well as reading for the connective tissue between these creative forces, towards a fuller rendering of what I am naming speculative materialism. With this in mind, I examine a number of different ways and examples of thinking with and through Black Constellation’s boundary-pushing creative work.

Black Present / Black Future

In an extended Pitchfork essay on the exhibition and the collective, titled “Event Horizon: Black Constellation’s Revolutionary Now,” writer Jonathan Zwickel grapples with Black Constellation’s work, and interviews Shabazz Palaces frontman, Ishmael Butler; in an understandably reluctant description of Black Constellation, Butler says:

Language is a very superficial way to communicate, and people feel like because you can read and talk that you're somehow superior than other people who communicate in different ways. It's not that it don't matter, but it just don't really matter to us like that… This is not to be exclusive or elite or separate, but to let you people understand that this notion of the individual being of ultimate importance is lame and weak and, most of all, corny. There's feast and then there's famine. Those that have been hungry, not allowed to participate in the feast—that's not going to continue. This blind, comment-less avarice and greed for nothing, selling out of the culture for no reason without really gaining anything but personal stuff—that's over.

Butler conveys how that which has been left out of knowledge-making, excluded from the veneration of ideas and theories communicated through language, obscuring modes in which meaning-making happens otherwise. Butler’s critique has layers, and still the articulation of the Constellation’s project in mission-like terms is impossible. It is the lack of, and resistance to branding—in the contemporary age of branding through the digital—within which Black Constellation operates. This again highlights their disinterest in forms of both colonial and capitalist capture, most notably in the art, media, and digital realms. Butler also intimates that the exhibition’s naming is, on the one hand, the necessary reclamation of and for sustenance—what we must then understand not as reparations, but rather, of redistribution. Even still, Butler is certainly insinuating that such a takeover by those who are hungry is a militant takeover—a takeover of revolutionary possibility, and a revolution itself. It is about the decentering and violent confrontation with those who hoard and consume and lord their wealth, knowledge, resources, and stolen goods over all others. It is not as though the feast is ending, but instead, it is done: in Butler’s words, “that’s over.”

This proclamation is enlivening: in using the second person, to not simply insinuate but to declare, that this period of violent and endless accumulation and predation has ended, is to think about a new dawn, a horizon, a dark optimism from the Black, indigenous, subaltern. But it is in the Black of Black Constellation that we must dwell: it is on this foundation that the Constellation rests. Of the Constellation, musician and Constellationeer Erik Blood says:

Blackness is a very important part of our thing. It’s a detail, but it’s an important detail. It’s our perception of reality. It affects the art that we make and how we view things in the world and how people listen to us. Black music is for everybody—but people still feel weirdly threatened.

What is vital to note is the way Blood situates Blackness as much about the audience reception as it is the artist’s productions—a reciprocal motion for the music, visual art, and multi-modal creative endeavors by the Constellation. In placing Blackness as the core of the Constellation, there is an acknowledgement that Blackness—as race, firstly, as color, as overcoded—determines planetary social, political, and economic relations. Rather than have a purely political agenda or message to impart, Black Constellation uses art and culture to celebrate Blackness and envision new and ever-expansive horizons.

Still, the fact of Blackness within the constellation’s structure is central, and arrives from a set of Black genealogies, Afro-futurism in particular, wherein new possibilities and visions for world-making are generated. Still, this imaginative capacity of other-worlds was born out of Afro-Futurist artists, writers, and thinkers like Octavia Butler, Sun Ra, Samuel Delany, Prince, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Wangechi Mutu, and others. We might fundamentally understand Afro-futurism as cultural production at the intersections between Black culture, technology, the imagination, mysticism, and liberation—a kind of Black sci-fi aesthetics. Like fantasy, these other-worlds, these utopias, are constructed as a necessary flight from the predatory violence of the world.

First defined by Mark Dery in his 1993 essay “Black to the Future,” and later theorized further by Alondra Nelson and many others, Afro-Futurism continues to be an important intervention. In Dery’s definition:

If there is an AfroFuturism, it must be sought in unlikely places, constellated from far-flung points…African Americans, in a very real sense, are the descendants of alien abductees; they inhabit a sci-fi nightmare in which unseen but no less impassable force fields of intolerance frustrate their movements.

Nelson provides an important critique and amendment to Dery’s formulation, by underscoring the necessity and vitality of Black speculation, experimentation, and abstraction:

The affiliation [Dery] established between AfroFuturist artists is limited to their shared racial background rather than to the improvisation and innovation of Black diasporic culture…Future vision is a necessary complement to realism, for the reality of oppression without utopianism will surely lead to nihilism. And we should not think of speculative cultural production as only “escapist,” but rather as holding important insights about people’s lived conditions.

Nelson’s intervention is significant for it points to the ways in which we render abstract and conceptual work by Black artists, and how to value the work for its futurist, utopic vision, but also to value its insights into the historical and material conditions of its varied cultural products. It is worth noting that Black Constellation does this for us on multiple planes, but has its critiques with the obsessive techno-logics at work. Nelson’s vital corrective to Dery’s definition of Afro-futurism points to the ways that such a genre invests in imagining otherwise for those historically disenfranchised. The ability to think, see, and create what appears impossible given the historical and current order of things, is one that underscores the necessity for future vision and speculation. As Nelson points out, it is in the utopic and visionary that we are able to see beyond the nihilism. To understand that for Black artists working in the mode of Afro-futurism, such moves are about working against the historical diminishment of life’s horizons; it is instead to speculate and invent new horizons.

I would argue that there is an ethical imperative in the speculation, experimentation, and abstraction in Nelson’s description of Afro-futurism. This imperative is related to Lowe’s point in “History Hesitant”: that is the need to imagine anew, far beyond the limits historically imposed on people of color, and most especially Black and Indigenous peoples. Lowe and Nelson make clear that, based on centuries of historical, material, cultural, and creative work, it is only more recently that we are able to apprehend how knowledges and works of cultural production from the Black Brown Indigenous Subaltern Alien have been cordoned off from one another, made to appear as minor, niche, folk, and traditional. Such forms of isolation through disciplinary boundaries made it difficult to see the ways in which there had always existed modes of radical relation in form, thought, method, and critique.

However, to Nelson’s point, it is necessary to think through what it means to envision other worlds through speculation, experimentation, and abstraction. This practice is crucial as it acknowledges that so much possibility is contingent on the Black Brown Indigenous Subaltern Alien creating it for themselves. That is to say that these forms and genres like Afro-futurism, as well as the visionary collaborative work of Black Constellation, are only possible because they emerged from deprivation and desire. Still, this is never to give credit to the powers that be for such cause—for creating such hunger amidst their feast—but rather to point to the ways in which, in the face of, and without interest in such power, the impulse to both create anew and honor what has always been, is beyond measure.

Paradise Sportif

I turn now to the opening track from Shabazz Palaces’ 2011 first studio album, Black Up. The track is titled “Free Press and Curl,” placed with chorus lyrics. With “Free Press and Curl,” we are given a rubric of freedom that is declarative, defiant, and celebratory—it is at once a recognition of the conditions of unfreedom that govern Black life and the assertion and affirmation of freedom in spite of, and in direct confrontation with, these lingering and foundational unfreedoms. It is a set of statements, with addressees: “Shit, you know I'm free, that's right, I'm free / To make pursuit to catch the stuff that holds me down / To capture my desires fashion out of this a crown / You know I'm free, shit, you know I'm free, pig, you know I'm free //.” The pig appears. This pig, as I read it, can connote a number of things: the pig could very well be the symbol of corporate greed, a capitalist, a chauvinist; it can also be a reference to the police.

In “Free Press and Curl,” we have an earlier example of Shabazz Palaces’ work that is at once subversive and playful, militant and joyous. In the refrain proclaiming “I’m free,” we get closer to understanding the expansive and exciting work the can be seen in the words of the Shabazz and the collaborations of Black Constellation. In Butler’s pronouncement, freedom here is presented as something that is addressed to another, and defiantly so or antagonistic toward. It is in this declaration that freedom is understood to be the foundation for the production of desire, the production of hope. Here, anything that holds down or suppresses desire or hope is not freedom—it is unfreedom. It is through freedom, through desire, through hope, that Butler asserts that he can “fashion out of this a crown.” Freedom has the power to exalt, to make royal, to make kings and queens. And such exaltation, such value and worth, such dignity is especially potent in the face of state power, as defined by Butler’s defiant address of the “pig.” It is useful here to pause on how these proclamations of freedom force an important reckoning with the conditions of unfreedom, specifically within a Black context. A helpful definition of unfreedom, a concept best coined and situated within black studies—specifically within studies of black abolitionism—comes from aforementioned scholar Sarah Jane Cervenak’s 2014 monograph Wandering: “a state of being ontologically codified as the nowhere, the detour, the backyard, and the movable and material sign of white diversion” (9). Such a definition points to the desire for freedom within blackness as an internal movement, one that takes seriously the promise of philosophical freedoms in addition to basic human freedoms. This definition, too, shows the limits of language insofar as it cannot capture the breadth of how unfreedom functions within black thought and being. Another possible avenue for theorizing this concept is through Sylvia Wynter’s idea of the colonization of the psyche, wherein Wynter elucidates how what appear as basic philosophical tenets from the Enlightenment period including being, truth, power, and freedom, are ultimately defined by race. As such, freedom is conceived of through the colonial lens of Western man, and unfreedom as a given for those outside of the West, outside of whiteness.

Moreover, given such a brief reference to the “pig,” Butler’s defiance is clear and in the face of state power. This presents an antagonism that is necessarily militant, insofar as the proclamation of a makeshift crown appears as a way of not only claiming personhood, rights, and livelihood, but most especially sovereignty. These declarations of sovereignty in the face of state and police power are deliberate, and offer new modes of pride, dignity, and glimmers of joy in the face of the obliterating force of systemic racism. Certainly, the asymmetry of power here undergirds the structures of state and police violence against communities of color. However, despite such unevenness, “Free Press and Curl” is one of many openings in imagining and therefore making possible such affective and political possibilities. This affective layer, along with the distinctive percussive and sonic power of “Free Press” make for a singular track, one that showcases Shabazz’s imaginative power. What defines this track affectively is pointedly articulated through the duo’s lyrics: “I run on feelings fuck your facts.” This defiance to be driven by feelings over facts is particularly salient given the way that the song, like many tracks on Black Up, changes tempo entirely after some time; that is to say, in my estimation, that the feel of the song changes entirely, lending the song a kind of unpredictability. On the surface, lyrically, this operation of feeling over fact is a vital reminder of Butler’s earlier statement on language: a remarkable and vital nod to other-worlds, other forms of knowledge and power, beyond and outside of both the West and whiteness. These other worlds are not only disinterested in such limited, unimaginative living and being, but wholly refuse, dismiss, and express a rigid disdain for “facts”: facts tend to represent, on the one hand, a world that is discernible and verifiable, and, on the other hand, a world where sensation, expression, speculation, experience, and theorizing are devalued or outright dismissed, considered invalid and excessive. This single line offers a kind of anticolonial expression, insofar as it very succinctly and effectively shuns Enlightenment, colonial models of thinking and knowing the world.

What is more, while defiant at first, declarative, bold, and righteous define Butler’s flow early in “Free Press,” the sound moves from, as Pitchfork names it, “stuttering, crunching drums and bass vibrations” to “a kind of galley song, a murky drift.” What is notable about most tracks from the album is the kind of spectral, haunting quality they each have, which can be attributed to each track’s unique reverberations, or reverb. These echoes, while created acoustically, electronically, and for sonic effect, consistently sound like the participation of other voices alongside Butler and Maraire, though the voices often feel ghostly, ancestral—like those of the undead. The reverb, particularly as it flows through “Free Press,” is an intriguing counterpoint to the defiantly-delivered vocals of Butler, militant in their proclamation of life, exaltation, and righteousness. Such echoes offer the song a kind of enduring presence, as though Butler’s utterances are refined and affirmed by their sounds. Ultimately, in song, Shabazz makes free its listeners from the pervasive realities of violence and harm placed on communities of color, most especially for Black people in the U.S. However fleeting, such a work of culture animates and enlivens its audience, and becomes an important component in thinking of both Shabazz Palaces’ and Black Constellation’s cultural and aesthetic contributions to what Cedric Robinson names the Black Radical Tradition.

Relatedly, a major part of Nep Sidhu’s work within Black Constellation has been the creation of a non-commerical clothing line, Paradise Sportif, reserved for Constellationeers and a select few. This line is designed and curated as what Sidhu deems the collective’s armor. It manifests the sacred place of textile and the material amidst the critique of the contemporary technologics of security and surveillance that is made increasingly central in the Constellation’s body of work(Figures 7-10).

Sidhu’s garments are a primary part of his exhibitions: including 2014’s “Your Feast has Ended”; 2016’s collaborative exhibit in Alaska with fellow Constellationeer Nicholas Galanin, titled “Kill the Indian, Save the Man”; 2016’s solo show “Shadows in the Major Seventh” in Surrey, British Columbia; 2018’s “Believe” in Toronto; and the recent solo Toronto and Calgary showings of his “Medicine for a Nightmare” exhibition. These works of art and armor are what I want to call “divine adornment,” where elements of multiple faith traditions, cultures, and creative practices are brought to bear on the garments: in a wider set of photographic renderings of Paradise Sportif, you can spot details like a kirpan, a small dagger from the Sikh faith, on the garments; or the Kufic script, the aforemoentioned form of Arabic calligraphy; there, too, are forms of head dress and cover that conjure various resonances. In theorizing how divine adornment operates through the vast and varied inspiration for Sidhu’s work, it is crucial to highlight the specific spiritual value of fabric, textile, and clothing to indigenous, Black, and the various diasporic cultures including Arab and Sikh with whom Sidhu engages. I am particularly invested in the notion that divine adornment, as seen in Paradise Sportif, works as armor that culls from varied traditions as a way of combining and therefore strengthening the protection they provide: in other words, these imbricated forms of fabric and style work as reinforcements for one another, and as such, deliver empowering cultural and political cues for those familiar with certain forms and ideas from these respective and shared histories and cultures. I argue that through such imbrication functions as way of exalting each separate and shared history and culture, and that such exaltation is a marker of divinity. It should be noted that in my placing spiritual value on this clothing line, I affirm an immaterial quality on what is and must be material in its most literal sense, material that envelops the body wholly: in this assertion, I refer to the grand, cocooning effect of many garments from the Paradise Sportif line, where the function of armor and protection is perhaps most apparent.

A welder by training, Sidhu’s work includes myriad textures and forms—from metal symbols and objects, to braidings of hair and yarn, with black always central and offset by primary colors. His collaboration with Nicholas Galanin from their “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” show was particularly notable. And here we have Galanin and Sidhu’s collaborative engraving through embroidery: “No Pigs in Paradise.” Sidhu defines the garment thusly:

No Pigs in Paradise speaks to an understanding of the specific histories of First Nations’ women and a clear understanding of women as essential to the restoration of First Nations’ societies. First Nations women are reaffirmed as the integral component to the reestablishment of balance and harmony. The path exists and the end goal is clear. The right path in this instance starts with protecting the women – leveraging ornament, textile, ceremony, incantation so they can be prepared to lead their families, communities and societies to an exalted, harmonious and prosperous status quo.

Sidhu’s centering of the First Nations women is important, in placing them as central to indigenous communities writ large. It also speaks to the variegated violence experienced by indigenous peoples, a deeply gendered system of violence. The message it offers can be read in other ways, but it could also be a warning, a notice, and an omen: that for those who prey on, exploit, and police the native, Black, Brown, subaltern, and alien, there is no place beyond—it is the implication that such a figure has already prospered and consumed to its limit, and that no good or pleasure can arrive as a result. This is the logic that “your feast has ended”: you have taken all you could, deprived others as a life-force, so nothing good awaits you, and you will be turned away beyond mortality. This is an anti-colonial logic.

Furthermore, I link what is happening in “Free Press and Curl” to Sidhu’s Paradise Sportif as a means of seeing the relations amongst different projects within Black Constellation. Galanin and Sidhu’s collaboration within and beyond Paradise Sportif conjures other kinds of ghostly or spectral connections as well. In Sidhu’s description of “No Pigs in Paradise” as centered on the significant place held by First Nation’s women, there exists a synergy and honoring of indigenous women that Sidhu recognizes and respects. Galanin’s role as an indigenous artist and as Sidhu’s collaborator is important in understanding the sharing and exchange of knowledge, as the artists of the collective are certainly creators, but that they, too, have political and cultural knowledges to share with each other and the world: this is one of many examples of the political education embedded in the creative work of Black Constellation. Their work emerges out of complex histories, belief systems, and spiritual relations that are made known or better known to one another through their process of collaboration—and this is something that may not necessarily reach the audience, nor is it necessarily intended to.

The resonances all inherit anti-colonial genealogies, however distinct and specific they may be. For example, I think of Galanin’s background as Tlingit, an indigenous Alaskan, and of Sidhu’s background as Sikh, as Punjabi, and as a diasporic, subaltern subject. There are spectral resonances, ones that connote the kinds of legacies of violence perpetrated on these very distinctive communities. For example, as mentioned, Sidhu’s work often incorporates hair as part of its multi-media composition. Hair holds a special significance for Sikhs, as it is often kept unshorn to express a devotion to Sikhi. Many Sikhs have long hair and often use forms of cover for it, most notably in the case of the turban. For many indigenous peoples, especially First Nations communities, hair is also kept and maintained as an expression of a connection to the natural world. Often, for native peoples, hair is shorn only in times of mourning as it represents a profound loss, and subsequently its regrowth demonstrates spiritual and natural movement forward from that loss.

However, historically, the notable keeping of hair by Sikhs and Native peoples has been used against them by repressive states like India, the United States, and Canada. I am specifically referring to the practice of scalping by several violent regimes: of early modern Mughal rulers against Sikh warriors and saints in the Punjab, North India; of early white settlers against Native peoples in the U.S. and Canada; and again of Sikhs in the 1984 genocide, where many Sikhs attempted to evade death by ridding themselves of the turban and cutting their hair so as to not be easily recognizable as Sikh. It must be noted that scalping was a way of symbolically expressing power over these populations, to send messages that any forms of non-compliance and resistance would not be tolerated by the emerging and present powers that be, respectively. Perhaps needless to say, these histories are often officially contested or denied by the state, as disavowal of historical violence against these two communities across oceans is par for the course. Nevertheless, evidence of these practices of scalping is well documented in scholarly literature by historians and anthropologists. This brutal practice was used by these states as a technology of social and political control over these marginalized communities, communities fighting for survival and land in asymmetrical but uniquely aligned ways. It is through such historical violence and trauma that we might start to better see how Galanin and Sidhu come to their work in and out of collaboration within Black Constellation. It is from these haunting legacies, through their communal survival, that we can to see the resonance of historical memory that permeate their work, and bring the two artists together. In these references to their collective lives that breathes life into the sharing of their worlds—Native and Sikh, red and brown, indigenous and subaltern.

In conjunction with others in the Constellation, most notably Shabazz Palaces, these artists provide myriad approaches to imagining our world as necessarily anti-colonial. In thinking through the chorus of “Free Press and Curl” in conjunction with Sidhu and Galanin’s work on Paradise Sportif here, I emphasize the curious ways in which they grapple along similar thematic lines—constellating histories and creating new horizons that reckon with colonial modes and models of being in the world, and impress upon such modes and models whole ways of anti-colonial living and being. In working through an anti-police framework, in exalting the feminine, in affirming non-linguistic modes of knowledge, in stressing anti-capitalist values, in recognizing vitality and futurity in the Black Brown Indigenous Subaltern Alien: in all of these ways, Black Constellation embodies an imaginative model of life, relation, and creativity. In their presentation of varied and incongruent struggles and forms of antagonism through their work, the Constellationeers each offer ways of thinking anew histories that have always been stripped of possible connectivity. In their gathering, in their creations both separately and together, their collective artistry pays homage to their respective and overlapping communities, while always presenting futurity in its most Black Brown Indigenous Subaltern Alien. It is in communion with one another that the greatest possible futures might manifest artistically, politically, and collectively.

Conclusion

Black Constellation, and the select works I highlight by Shabazz Palaces, Nep Sidhu, and Nicholas Galanin, provides a significant example of thinking about the possibilities of building solidarity through cultural production. By placing art across various modes and practices together with a loose but ultimately expansive and cohesive vision, the Constellationeers demonstrate and embody a multitude of histories, knowledges, and belief systems that, when assembled, apprehended, and interpreted, make possible relations across peoples and time. Of course, this is not to say that my particular reading of select Black Constellation work is definitive in any way; rather, I find what the Constellation offers to be open and expansive, making room for apprehending and perceiving in singular modes. Still, what I aim to show is how there exist resonances between the projects and of which the members of the collective create works. It is with these echoes of the past that reverberate with echoes of other pasts, what lies between histories and how they envision futures in which I am most invested—this speculative materialism quintessential and embedded in the Constellation’s cultural production.

In many ways, these engagements harken back to Lisa Lowe’s words, wherein we must confront the discrepancies in how histories have been separated by liberal projects of modernity, wherein linear timelines, frameworks, geographic separation into regions and whole worlds entirely—first and third; North and South—reign supreme to do this way. Instead what Black Constellation can show us are ways of working not simply around such a problem, but how to see beyond and without such arbitrary divisions. While this feature of their work might not cohere to conventional modes of relating histories and regions, it instead demonstrates a radical model of creating and laboring in solidarity. Solidarity means something wholly inventive when rendered in connection with the kinds of artistic work that the Constellationeers are producing. That is to say that these forms of collaboration exhibit the knowledge that echoes from their distinctive histories. Such knowledge is rendered disparate by imperial projects that would choose for the Black Brown Indigenous Subaltern Alien to not only forego seeing the connections between, for example, different iterations of colonialism or the use of brute force and violence on bodies of color, but to disavow it entirely. This is what it means to see the reverberations between their work and encoded political and ethical commitments to their respective communities and to communities of color in North America.

What is more, Black Constellation presents us with collaboration that works in solidarity unintentionally. Given that their collective is not any sort of political organization, it is in cultural production that they are tethered by a shared vision against state power and police power: hence, “YOUR FEAST HAS ENDED” and “No Pigs in Paradise.” Their shared commitment against state apparatuses is derived from long-held struggles against such power: legacies and ongoing social movement struggles by Black communities in the Civil Rights movement and in the Black Lives Matter movement; in the tensions and struggles between indigenous peoples and police power, especially First Nations women and the movement in Canada to achieve justice for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG); and in the continued struggles between Punjabi Sikhs and Indian police in their continued surveillance, detention, and torture of supposed Sikh militants since even before the Indian government’s attempts at Sikh genocide in 1984. Through such examples, while primarily contemporary, it might become clearer how Black Constellation’s members are able to recognize in one another a relation—a radical kinship—that is not always readily available for easy or quick recognition or understanding.

I find that Black Constellation’s radical kinship is a model for sustainable solidarity practices. In their endeavor to not be bound by a mission or a body of work that easily coheres, they are following their creative impulses and drives respectively and collaboratively. Nevertheless, I argue that the Constellation is able to produce work that is overtly and implicitly anti-state, and that both engages and invests in theorizing and practicing futurity in their work, creating lines of flight and expansive horizons for the Black Brown Indigenous Subaltern Alien. Given that such lines and horizons can be seen as utopian, I view Black Constellation’s labors of love as part of multiple radical traditions, traditions that follow the historic examples and legacies of solidarities including: inter-ethnic and interracial solidarities, exemplary in the creation of ethnic studies; or, in the gathering of the formerly colonized in the landmark Bandung conference or, in modern and contemporary calls for radical internationalism in sites across the globe. It is with their respective and collective practices of solidarity; in their engagement, creative pursuit, and boundary-pushing of multiple radical traditions; and through their diverse and divine knowledges, histories, and myths, that Black Constellation manages to help fashion new possible futures of care and connection, defiance and desire, freedom and struggle. It is in these futures that we would want to live, and live with others in solidarity and radical kinship.

Works Cited

Alley-Barnes, Maikoyo. “Black Constellation,” accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.maikoiyo.com/black-constellation.

Cervenak, Sarah Jane. Wandering: Philosophical Performances of Racial and Sexual Freedom, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

Dery, Mark. “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delaney, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose,” from Mark Dery, Ed., Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), 182.

Frye Art Museum. “Expanding the Now: The Continual Line,” 2014, accessed June 15, 2019, https://fryemuseum.org/calendar/event/5577/.

--“Your Feast Has Ended,” 2014, accessed June 15, 2019, https://fryemuseum.org/exhibition/5518/.

Galanin, Nicholas. “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” Artist Statement, 2016, Anchorage Museum, accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.anchoragemuseum.org/exhibits/kill-the-indian-save-the-man/artist-statement/.

Gopinath, Gayatri. Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).

Lowe, Lisa. “History Hesitant,” Social Text, 33 no. 4 (December 2015), 85-110.

Martineau, Jarrett. “Creative Combat: Indigenous Art, Resurgence, and Decolonization,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Victoria, 2015), 212-45.

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics,” Public Culture, 15 no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11-40.

Nelson, Alondra, Ed. Afro-Futurism: A Special Issue of Social Text, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002)

Oxford Reference. “Constellation,” accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095633862.

Robinson, Cedric. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Second Edition), (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

Shabazz Palaces. “Free Press and Curl,” Genius, accessed June 20, 2019, https://genius.com/Shabazz-palaces-free-press-and-curl-lyrics.

--Sub-Pop Records, Megamart, accessed June 15, 2019, https://megamart.subpop.com/artists/shabazz_palaces.

-- Welcome to Quazarz,” Genius, accessed June 20, 2019, https://genius.com/Shabazz-palaces-welcome-to-quazarz-lyrics.

--“Welcome to Quazarz,” (video), dir. Nep Sidhu, July 13, 2017, accessed June 20, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URVpPq9KKlM.

Sidhu, Nep. “Nep Sidhu” (artist website), accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.nepsidhu.com/.

Vizenor, Gerald. Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation--An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review, 3 no. 3, (Fall 2003), 257-337.

Zwickel, Jonathan. “Event Horizon: Black Constellation’s Revolutionary Now,” October 27, 2014, Pitchfork, accessed June 15, 2019, https://pitchfork.com/features/article/9530-event-horizon-black-constellations-revolutionary-now/.

Notes

- The author wishes express deep gratitude to both Sue Shon and Katherine Lennard for their invaluable feedback, encouragement, and generosity with this piece.

- Anupma Mistry, “Masters of the Now: Shabazz Palaces and Black Constellation,” August 22, 2014, Wondering Sound, accessed June 15, 2019, http://www.wonderingsound.com/feature/black-constellation-nep-sidhu-interview/.

- “Your Feast Has Ended,” 2014, Frye Art Museum, accessed June 15, 2019, https://fryemuseum.org/exhibition/5518/.

- “Expanding the Now: The Continual Line,” 2014, Frye Art Museum, accessed June 15, 2019, https://fryemuseum.org/calendar/event/5577/.

- “Black Constellation,” Maikoyo Alley-Barnes, accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.maikoiyo.com/black-constellation.

- “Nep Sidhu Brings His Vision to the West,” April 8, 2016, The Screen Girls, accessed June 15, 2019, http://thescreengirls.com/nep-sidhu/

- “Shadows in the Major Seventh,” 2016, Nep Sidhu Exhibition Catalogue, Surrey Art Gallery, accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.surrey.ca/files/ShadowsintheMajorSeventhCatalogue.pdf

- Black Constellation’s work has only sparingly been written about, and this has its own purpose in keeping their work underground while also allowing their individual and collaborative work to appear as it may, online and in person. See “Moment Magnitude: The Black Constellation, October 2012-January 2013,” Frye Art Museum, accessed June 15, 2019, https://fryemuseum.org/momentmagnitude/artist/the_black_constellation; Jonathan Zwickel, “Event Horizon: Black Constellation’s Revolutionary Now,” October 27, 2014, Pitchfork, accessed June 15, 2019, https://pitchfork.com/features/article/9530-event-horizon-black-constellations-revolutionary-now/; “New Off the Spaceship: A Bluffer’s Guide to Black Constellation,” July 31, 2018, KEXP, accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.kexp.org/read/2018/7/31/new-spaceship-bluffers-guide-black-constellation/; “Black Constellation,” Art Radar Online, accessed June 15, 2019, https://artradarjournal.com/tag/black-constellation/; “Black Constellation,” 206Up: A Seattle Hip-Hop Blog,” accessed June 15, 2019, https://206up.com/tag/black-constellation/.

- Originally used in legal studies in the eighteenth century, survivance is a term now used within Native and indigenous studies, first utilized by scholar Gerald Vizenor. He defined the term thusly in his 1999 monograph Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance: “an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name. Native survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry” (vii). I use it here to suggest that it operates against North American settler colonial logics.

Another helpful way of thinking about the mode of abstraction the Constellation engages is Sarah Jane Cervenak’s theorization of wandering for Black feminist philosophy and culture writ large: Cervenak argues that not all works of culture, especially Black culture, must be readily knowable, interpreted, or readable. Specifically, she asks of us, and elucidates wandering’s theoretical expansiveness:

What would it mean to leave alone that which cannot be read or that which resists epistemological urgencies at the heart of such readability and knowability?…Wandering’s assertion that enactments of philosophical desire are possible despite and because of their resistance to verifiability is troubled by its own tendency to make much of that possibility…I advance the possibility of philosophical abundance against racist, sexist, classist, spatial, ableist, logocentric, homophobic, and ocularcentric assumptions that presume both its impossibility and absence…[Wandering is] not only a mutant form of enunciation, articulation, and textuality, but also an enactment that signals the refusal of all three qualities.(3)

Cervenak’s investment in thinking through what it means to value and find profound philosophical insight and truth in work that exists against readability, verifiability, and knowability is powerful. Her description of wandering as a theory of reading, thinking, and being, puts into context how such work that falls into this category operates against colonial knowledge-making, which she situates in the Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment periods. With Cervenak’s theory of wandering, studying Black Constellation’s work through abstraction and its use of illegibility offers ever more immense potential for thinking, too, of its anticolonial commitments.

Perhaps most apparently, by thinking of Black Constellation’s work as linking the Black and Brown, through Africa, South Asia, and Black and Indigenous North America, we are confronted with the linkages and intimacies that have predominantly been obscured by discrete histories and knowledge production abiding by nation-state rubrics. These relations are given ever more fleshing out in the work of Lisa Lowe, whose The Intimacies of Four Continents provides a pathbreaking intellectual contribution in thinking across and relationally against established methods of inquiry; in “History Hesitant,” Lowe writes:

I suggest that in order to account for differentiated yet simultaneous colonial histories and modalities, we must retire the convention of comparison as an operation that presumes equivalences between discrete analogous units, in order to be able to think differently—politically, historically, and ethically—about the important asymmetries of contact, encounter, convergence, and solidarity. When reading connections and conjunctions across archives and geographies, it is often necessary to break with customary modes for organizing history and to devise other ways of reading beyond the given presumptions of a rational, synthetic system, a developmental teleology, or symmetries of cause and effect.

That this is an ethical task is what interests me most, as it aids in thinking about power with attention to its uneven and unequal distribution spanning contexts. It is with this deep and abiding interest in how the construction of borders--through geography, discipline, historical periodization, form and genre, as well as epistemology--have been constructed as a means of ordering the world in ways that reproduce prevailing systems of power. These false walls are what Lowe is disrupting when she underscores “contact, encounter, convergence, and solidarity.”

In Lowe’s formulation, the possibility of solidarity both despite and because of the historical absence or disavowal of connection and relation is crucial. Still, her emphasis is on asymmetry and not on comparison, making way for thinking through “contact, encounter, convergence, and solidarity.” There is a necessary embraces of the dissimilar and unevenness across these connections, but nevertheless the connections are imperative. Here is where Lowe highlights that what we know of the disciplining of history and the ways in which such practices submerged and suppressed the possibility of thinking relationally and connectively in ways that might have produced new and incredibly generative modes of knowing and relating in the world. In some ways, Lowe’s important intervention shows how vital forms of creative work and cultural production often are in thinking with and in collaboration, across what appear to be vast or major forms of difference.

- A useful analytic is found in what queer studies scholar Gayatri Gopinath calls acts of queer curation; in her recent work, Unruly Visions, Gopinath describes this method and analytical approach as that which seeks to “reveal not coevalness or sameness but rather the co-implication and radical relationality of seemingly disparate racial formations, geographies, temporalities, and colonial and postcolonial histories of displacement and dwelling.” The collective work of creation and curation is one that sees the act of constellation as a form of mutual and co-conspiratorial production. However, their imbrication and co-constitution are rendered through creation primarily, rather than curation. In fact, Black Constellation’s mission is never singularly defined or made manifest through any kind of particular statement, manifesto, treatise, and the closest we come are Alley-Barnes’s aforementioned words, and the lyrics of its musical artists, most centrally Shabazz Palaces. Nevertheless, while there is singularity in their respective work, in their gathering, their radical relationality, as Gopinath articulates it, amongst what is disparate, specific, and contingent, emerges what is always already urgent and necessary in ways difficult to express. That is to say that in their constellation, the work and its attendant processes, are never normative and their coherence does not abide by prevailing logics and systems. Rather in their creative intimacy, in their clustering, there exists another mode of meaning-making that is akin to, it feels like, it gives us the sense of curation.

- Jonathan Zwickel, “Event Horizon: Black Constellation’s Revolutionary Now,” October 27, 2014, Pitchfork, accessed June 15, 2019, https://pitchfork.com/features/article/9530-event-horizon-black-constellations-revolutionary-now/.

- Ibid.

- I am indebted to indigenous scholar Jarrett Martineau’s work on Black Constellation, what he names as part of his theorizing “decolonial constellations of love and resistance.” He reads the constellation as “a strategic, relational arrangement of space and subjects that provides Indigenous artists, and allied communities of struggle, with a mutable form for shared creation and action that can be networked to produce collective power.” While he centers indigenous artists as part of his thesis, Black Constellation provides an important example of coalition and solidarity as a decolonial strategy broadly speaking. As such, I find the emphasis on the decolonial possibilities of the constellation to be invigorating insofar as it emphasizes the collective’s strategic evasion of forms of capture, specifically as property or possession within a capitalist market. That is to say that Black Constellation’s body of work remains relatively illegible and purposefully underground, or fugitive, as Martineau puts it.

- Martineau argues, too, that Black Constellation’s work is both Afro-Futurist and Indigenous Futurist. However, for the sake of my argument, I focus on the heavy Afro-Futurist sensibilities of the Constellation. As is clear, much has been written about Afro-Futurism, sources including: Reynaldo Anderson & Charles E. Jones, Eds., Afro-Futursim 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness, (New York: Lexington Books, 2017); Andre Carrington, Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016); Sandra Jackson and Julie Moody-Freeman, Eds., The Black Imagination: Science Fiction, Futurism, and the Speculative, (New York: Peter Lang Inc., 2011); Alondra Nelson, Ed. Afro-Futurism: A Special Issue of Social Text, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002); Ytasha Womack, The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013); Paul Youngquist, A Pure Solar World: Sun Ra and the Birth of Afro-Futurism, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016).

- Mark Dery, “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delaney, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose,” from Mark Dery, Ed., Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), 182.

- Alondra Nelson, Ed. Afro-Futurism: A Special Issue of Social Text, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002).

- “Free Press and Curl,” Shabazz Palaces, Genius, accessed June 20, 2019, https://genius.com/Shabazz-palaces-free-press-and-curl-lyrics.

- See footnote 10: Cervenak, Sarah Jane. Wandering: Philosophical Performances of Racial and Sexual Freedom, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

- See Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation--An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review, 3 no. 3, (Fall 2003), 257-337.

- Eric Grandy, “Shabazz Palaces, Black Up,” June 27, 2011, Pitchfork, accessed May 15, 2020, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/15570-black-up/

- Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Second Edition), (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

- Nep Sidhu (artist website), accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.nepsidhu.com/

- “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” Nicholas Galanin, Artist Statement, 2016, Anchorage Museum, accessed June 15, 2019, https://www.anchoragemuseum.org/exhibits/kill-the-indian-save-the-man/artist-statement/.

- Hair is a major part of his central work in Nep Sidhu’s latest exhibition, “Medicine for a nightmare (they called, we responded).” See Mercer Union, “Medicine for a nightmare (they called, we responded),” 2019, accessed June 15, 2019, http://www.mercerunion.org/exhibitions/nep-sidhu-medicine-for-a-nightmare-they-called-we-responded/; Samantha Edwards, “Artist Nep Sidhu Revisits a Painful Chapter in Sikh History,” February 12, 2019, Now Toronto, accessed June 15, 2019, https://nowtoronto.com/culture/art-and-design/nep-sidhu-mercer-union/.

- On hair and Sikhism, see Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair, Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed, (London: Bloomsbury, 2013); Emily Nesbitt, Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction, (London: Oxford University Press, 2016); G.S. Sidhu, Sikh Religion and Hair, (Amazon Digital Editions, 2008); Nikki-Guninder Kaur Singh, Sikhism: An Introduction, (London: I.B. Tauris & Co., 2011).

- On hair and Native American history, see Joanne Barker, Ed., Critically Sovereign: Indigenous Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Ned Blackhawk, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008); Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, (New York: Beacon Press, 2015); Kathleen DuVal, The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007); Mishauna Goeman, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping our Nation, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

- On the anti-Sikh violence of 1984 and Indian state disavowal, see Jyoti Grewal, Betrayed by the State: The Anti-Sikh Pogrom of 1984, (London: Penguin Books, 2007); Manoj Mitta and H.S. Phoolka, When a Tree Shook Delhi: The 1984 Carnage and Its Aftermath, (Delhi: Lotus Roli Books, 2008); Jarnail Singh and Khushwant Singh, I Accuse, (London: Penguin Books, 2011); Sanjay Suri, 1984: The Anti-Sikh Riots and After, (New York: Harper Collins, 2015).

- Ibid.

- See much of endnote xxxiii, especially Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, (New York: Beacon Press, 2015). See also Glen Coulthard, Red Skin White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014); Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017); David E. Stannard, American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

- On Sikhs and the history of scalping, see Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, (London: Oxford University Press, 2005). On Indigenous peoples and the history of scalping, see Philip Davis, Scalping the Great Sioux Nation, (New York: Hamilton Books, 2009); Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, (New York: Beacon Press, 2015); Adam Fortunate Eagle, Scalping Columbus and Other Damn Indian Stories, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014); Jeffrey Ostler, Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

- For reference to MMIWG, see Memee Lavell-Harvard and Jennifer Brant, Eds., Forever Loved: Exposing the Hidden Crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada, (Bradford, ON: Demeter Press, 2016).

- Here I am referring to utopian both in the context of Afro-futurism and in relation to its denotation of pieces from Sidhu’s non-commerical clothing line Paradise Sportif, “No Pigs in Paradise,” which operates as a kind of mantra across many works by Black Constellation. In thinking about utopianism, I point to the ways in which certain kinds of ideals are achieved within the collectivity and shared creativity of Black Constellation.

- For a detailed history and set of accounts on the landmark 1955 Bandung conference, see Amitav Acharya and See Seng Tan, Eds., Bandung Revisited: The Legacy of the 1955 Asian-African Conference for International Order, (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2008); Christopher J. Lee, Ed., Making a World After Empire: The Bandung Moment and its Political Afterlives, (Columbus: Ohio University Press, 2010); Jamie Mackie, Non-Alignment and Afro-Asian Solidarity, (London: Editions Didier Millet, 2005); Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World, (New York: The New Press, 2008).

- For contemporary work on internationalism and solidarity, see David Featherstone, Solidarity: Hidden Histories and Geographies of Internationalism, (New York: Zed Books, 2012); Anne Garland-Maher, From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism, and Transnational Solidarity, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018); Anjana Raghavan, Towards a Corporeal Cosmopolitanism: Performing Decolonial Solidarities, (New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2017).

Cite this Essay

Singh, Balbir K. “‘No Pigs in Paradise’: Speculative Materialism in the Spirit of Black Constellation.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 36, 2020, doi:10.20415/rhiz/036.e04