Heterosexuality remains the dominant paradigm for family, sexuality, romance, gender, parenting, reproduction, even feminism. (Hennessy 152)

Thus far, any queer character on television has reinforced a heterogender system (Hennessy 158). Though the characters may be queer, the storylines are straight. Will and Grace has become popular with heterosexual audiences who sit in front of their televisions every week hoping that Will (gay male) and Grace (straight female) will become a couple and have a child together, therefore putting even queer characters into heterosexual relationships. In fact, Grace is Will's only successful relationship, a relationship founded on their once heterosexual coupling. Jack, Will's flamboyant sidekick, is not allowed a relationship either. The jokes about Will as feminine, because he is gay, and Grace as masculine, in a sense, support gender stereotypes within a heterosexual relationship with Will seen as the wife and Grace the husband (and the only character with any sexual conquests) (158). The same is true for the relationship between Jack and Karen. This normalizes heterosexuality and prevents the queering of traditional relationships. While Will and Grace has allowed for the increased visibility of queers, it has done little for queers as people. The way the characters and their lives are portrayed does not threaten the institution of heterosexuality, but rather solidifies it.

While most shows reinforce heteronormativity, The L Word picks up the battle from where former shows, such as Ellen, have left off; it is a show with lesbian and bisexual characters that are actually queer. Where the characters are lacking in diversity, the situations they find themselves in and the personalities of the characters themselves are quite diverse. Most lesbians can find a story they relate to, whether it represents them or someone they know, and some can relate to almost every story. All of these situations represent a process of discovering identity, whether or not every single queer experiences that particular process. Sadly though, The L Word lacks intellectualism; characters are rarely seen reading or discussing politics (Leonard). Though art does exist on the show and there is the occasional feminist outburst or statement on some sort of -ism, the art and politics on the show seem to be little more than extras, popping up only to disappear again, while the primary focus remains on fashion and sex (relationships). Regardless, the show helps to create what Adrienne Rich labels "lesbian existence" and is part of a "lesbian continuum," through the show's presence in mainstream culture (Rich 322).

Lesbian existence is reified through The L Word's realistic

portrayal of sex. Never before have we seen women on mainstream TV or Hollywood film so free with sexuality. Sex scenes in mainstream television and film have been focused on men and are more about male pleasure than female. Claire Colebrook talks about the queer body as being subjective while the straight body is objective, because of its ability to be productive (228). Lesbians are used objectively, for male pleasure, in pop-culture and are most often left sexless. Ideologies of sex have been heterosexualized and centered around the penis. Though it is possible to have sex without a vagina, mainstream society does not allow sex to exist minus the phallus. The phallus is sex. Traditionally, men have been allowed to have intercourse freely and however they want, while women are only allowed sex for reproductive purposes. Thus, The L Word begins to push away the subjectivity of the queer body, taking sex from males and giving it to females. The women of The L Word control their sex lives; they are allowed to find pleasure in sex. They are no longer objects of pleasure for men, holes to be drilled. They are active participants, making decisions about what they want sexually. The L Word has shown trips to sex shops, use of sex toys, bondage and dominance, and vampire lesbian sex, as well as discussions of private parts. Similar to Sex in The City, The L Word allows for sexual freedom (exploring sex and sexuality).18

Though the relationships are complex and mostly realistic, and sex is expressed freely, there are still many problems with these storylines. The sex scenes are generally not romantic or sensual. That is, there is little, if any, foreplay involved and the scenes are quick and to the point. This is okay for characters like Shane or Papi, who do not, for the most part, do relationships, but it is unrealistic for this lack of sensuality to persist throughout the relationships of other characters. However, there are rare exceptions to these rushed sex scenes. One departure from this lack of romance was in episode 206. Tina attends a party for the Peabody Foundation and Helena sneaks out and calls Tina on her cell. Prior to this, the two have flirted and gone out socially. They each are sitting and talking, and though Tina's shirt is off pretty quickly, there is some touching, caressing, and kissing before they jump into the sex. Shane also has a moment of romance when she begins a new relationship with Carmen, much to her own surprise. It is understandable that the time limitations on an hour show does not allow for deep, meaningful sex scenes, but it is possible to still make a scene sensual without taking much time.

This lack of romance and foreplay could inadvertently support the only sexual image of lesbians, lesbians as predatory. Possibly as a result of the lack of sensuality in its sex scenes, the series has been criticized for representing lesbians as such, but also as "sex-obsessed" (Thompson). This has also been used as evidence to support an argument that Chaiken is trying to appeal to a male audience. In defense against the argument that The L Word is oversexed, it must be noted that heterosexual television, or film, show just as much sex (as does QAF) but have not been criticized for trying to pull in a certain audience.19 So why is The L Word accused of catering to straight men? Perhaps it is the feminine characters and the way the show has been increasingly sexual since the first season. Regardless of this controversy over sex, these "sex-obsessed" scenes are part of the realism of the storylines, or perhaps the characters themselves. Characters like Shane and Papi, who enjoy sex without the complication of relationships, are often seen in mainstream television. This is a realistic character or role, but one which we are not use to seeing played by a woman, except in porn.

Another problem with the show's storylines arises when supporting characters abruptly disappear, thus disrupting the flow of the stories. In an early episode, Alice was dating a man. She claimed, "I am looking for the same thing in a man that I am in a woman." But, this was no ordinary man; Lisa (see the characters section on supporting characters) was a "male lesbian." This was an interesting character idea, and many of us have known men that would make good lesbians, but Lisa disappeared from the show as quickly and strangely as he entered it, as did Alice's bisexuality; she has not dated a man since. Lisa's disappearance was meant to make room for Alice to explore her relationship with Dana, but the mystery of the departure is problematic. And potentially sad, since Alice, the only bi-identified character, is becoming less bisexual and more lesbian. Tina has a relationship with a man in season 3, which continues into the fourth season, but even while in this heterosexual relationship, Tina identifies as a lesbian. Both of these situations diminish the validity of bisexuality as a viable orientation.

Several other characters disappear without much explanation. In another episode, Kit is hosting a drag show at a club where she works. At the end of the show, she approaches one of the drag kings, Ivan (supporting characters), and complements him20 on his performance. From here their relationship develops. Bette jokes that Ivan is Kit's husband, foreshadowing a possible relationship between the two. When the first season ends, the viewer is left to think (hope) that Ivan will become a fixture and in the second season, the relationship develops further. In one romantic scene between the two, he repairs Kit's car and gives her a key to his apartment. But, the first time Kit uses the key, she encounters a partially naked Ivan who has not yet finished his transformation into a man. He is upset by this and there is no further interaction between the two, except to finalize Kit's purchase of Marina's former coffee shop. Ivan had agreed to become her financial partner and does not back out on this deal. His swift departure is hard to believe, especially since he cared so much for Kit. Ivan later rejoins the show in episode 209, but was cast out in the same episode by Kit, when she found out that Ivan was in a long-term relationship with a "straight" woman, another strange and unrealistic departure.

It is understandable that characters move in and out of relationships; this is realistic. It is also probable that supporting actors will come and go from the show, especially since their eventual departure is foreshadowed by the storyline. What is unrealistic is the suddenness of these disappearances, that the departure itself never happens; characters just vanish and the viewer is left to make assumptions about what happened. It makes some storylines more unbelievable.

But these are all minor problems. It is what is left out of the show, an actual discussion of the taboo themes that are brought up, that is most problematic. While The L Word has gone into subjects like lesbian sex and sex toys, it has overlooked or brushed aside issues like race and transgender that need to be deconstructed when they are discussed on the show rather than brought up once and dropped forever. Transgender has been a taboo in the gay and lesbian community, much in the same way that "homosexuality" is a taboo in the heterosexual community. While masculinity for women is a valid identity in the queer community, The L Word, in its first three seasons, seems to tie it in with transgender, creating a binary that reifies the lesbian identity that the series created in its first two years. The series has created an identity hierarchy, with race playing second fiddle to sexuality, if it is discussed at all. Bette's biraciality is explored briefly in a few episodes in the first season, alongside the discussion of having a child, but does not seem to be a part of her life beyond that one issue. Her identity thus seems solely based on her sexuality. Ivan's identity is also simplified. At first it seems that he is a drag king, as some of the characters use "she" when talking about Ivan. Regrettably, Ivan's true identity is never explored, and his departure reinforces the transphobia that exists in the queer community. With as much gossip as goes on between the characters, a discussion amongst the friends could have easily remedied this need for defining transgender and transsexuality. While producers may be trying to further this discussion with the emergence of Max, I question their methods of exploring the issue and worry that it will only further transphobia.

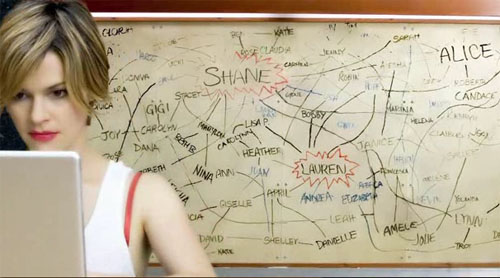

Unfortunately, identity is not the only subject relegated to a backdrop. Many social issues are also pushed under the rug without much serious exploration. In one of the last scenes of the first season, Bette comes home to find Tina upset. Tina saw Bette having a moment with her carpenter, Candace, at the art show opening, and realizes that Bette has cheated on her. She yells at Bette. What follows is a violent scene with Tina as the victim of domestic violence and rape.21 Tina eventually gives in to her aggressor, but right before the credits roll, we find Tina in Alice's apartment where she uses Alice's web of relationships,22 to tell her that Bette cheated on her. The entire scene between Bette and Tina was uncomfortable to watch, but is most problematic in that it is never addressed in the second season, nor in Tina's conversation with Alice. The two, of course, break up, and almost everyone is angry with Bette, but the violence of the situation is overlooked and the two eventually get back together. Domestic violence is a serious problem in queer and straight relationships and The L Word does well to present it as a storyline, but to both not acknowledge it as such and ignore the complexity and magnitude of the situation demeans society's concern over violence and rape.

We see the same inattention with the issues of suicide and substance abuse. While several characters attempt to kill themselves, suicide as an epidemic, especially in the queer community, lacks any exploration between the characters. Marina's suicide is merely mentioned to explain her departure from the first season. No one talks about cutting (see footnote 17 for explanation) or Jenny's suicide attempt at the end of season 2. And Shane's drug-induced haze in the beginning of season 4 is introduced by her floating, most likely unconscious, in the ocean; this scene could certainly be interpreted as a form of attempted suicide. At the very least, substance abuse is a problem here and also seems to only appear when needed for a storyline. Shane's drug problem is mentioned once before in season 1 and she seems to be able to stop cold turkey in both cases. Kit's alcoholism is simply discussed when her life is problematic and she attends AA meetings only when another character is involved. Otherwise, it is not seen as a problem. The issue of substance abuse is rarely discussed amongst the other characters. The problem just seems to vanish and the characters move on.

Alice and her web of relationships. Screenshot from credits of season 3.

In watching any show that is portraying the lives of so many people in a short period of time, you have to expect some problems. In spite of these disparities, the storylines are the most realistic and diverse part of the series. The L Word itself may seem predatory and sex-obsessed to some, but in light of the images that lesbians, and women in general, have had in the past regarding sex, for many lesbians, the stories are empowering and sexually freeing. They demonstrate variations both in the process of coming out and in sex as an act. The L Word tackles issues that other shows avoid, but unfortunately, some of these issues are lacking depth and are thus demeaned due to absence of the analysis and follow through needed when addressing such serious issues. The show also reflects an apparant belief, on the part of its producers, that it can cover in one discussion issues like race, abuse and gender identity that do not go away after you bring them up once. While the stories portray positive sexual images for women who have thus far been closeted or erased from popular culture, the lack of deconstruction of problematic themes and complex identities does as much damage as the negative stereotypes of queers in pop-culture. It is this diminishing of issues, mixed with Chaiken's new capitalistic image of lesbians, that leads some viewers to disregard the empowerment offered by a show like The L Word.